Introduction

Although several authors have pointed out that strategy and planning are—and should be—distinct, most companies continue to equate strategic planning with strategy formulation, referring to the resulting plans as their strategy.

In any case, there seems to be little disagreement that both strategy and planning are needed. Those who see them as distinct often agree that planning is, as Henry Mintzberg put it, the ‘programming of the strategy.’

Regardless of the definitions, this article addresses the fundamental ineffectiveness of what most organizations call ‘strategic planning’—whether the goal is to produce a ‘strategic plan’ or to ‘program the strategy’ by making next-level decisions on how to implement it.

This is not to say those distinctions are meaningless. However, regardless of how strategy and planning are defined, what is typically referred to as strategic planning remains fundamentally ineffective for five key reasons:

- The purpose is to create a plan, rather than to make decisions.

- No one has real ‘skin in the game’ regarding what goes into the plan or how it impacts the business.

- There is no mechanism to test and revise any of the ideas in the plan based on real-world data.

- The plan and the tools used are deterministic, while the real world is probabilistic.

- Despite its holistic scope, the focus and ‘planning’ occur on parts of the company.

Because of these key characteristics, it doesn’t matter how the strategic planning is carried out (or called, for that matter), what the further details, process steps, or tools are; nor does it matter how skilled the participants are or how much effort they put into it.

None of that can change the fact that the entire exercise will inevitably be ineffective.

#1 Plan Creation, Instead of Decision-Making

The biggest issue with what most call ‘strategic planning’ is its purpose: to ‘create a plan.’ This differs from the more effective purpose of ‘making decisions’ in one critical aspect: plans have no impact on performance; only decisions do.

While a plan is technically a coordinated set of decisions, it’s entirely possible to make plans without any intention of carrying them out—let alone without accountability (‘skin in the game’) for what is included in them.

While this may sound like an academic distinction, its practical impact is both real and significant. When ‘strategic planning’ focuses on ‘plan creation’ rather than decision-making, plans often become wish lists of “it would be fun to do this” rather than serious commitments involving real trade-offs, risks, and consequences.

As a result, as Kaplan and Norton put it, “Typically, such plans then sit on executives’ bookshelves for the next 12 months.”

For example, a company might plan to shift to sustainable products. Regardless of the level of detail (which, depending on the definition of strategic planning, may vary), to be effective, this shift would require new investments and reallocation of existing resources across R&D, marketing, sales, operations, and possibly even a geographical focus (such as SG&A changes between business units), target revisions, etc.

Yet ‘strategic planning’ typically lacks any of those decisions. While it may produce PowerPoint slides that describe ‘what could be done, maybe, at some point, somewhere,’ at the end of the day (at the end of the strategic planning), no new investments are made, no resources are reallocated.

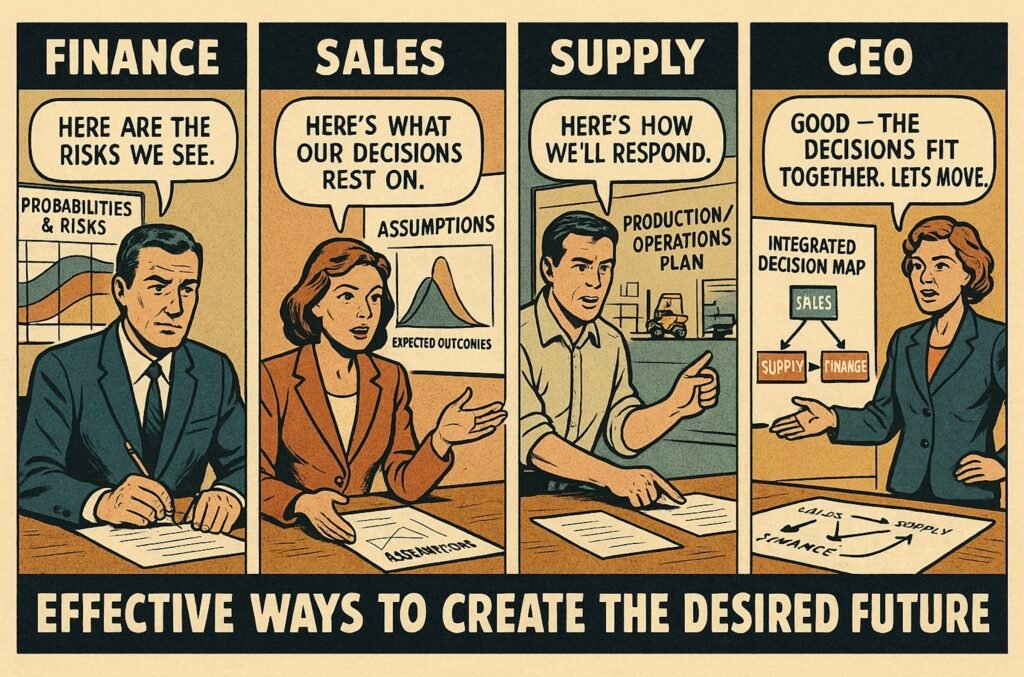

Moreover, while effective strategy is about focus and fit, strategic planning is typically about none of that (Picture 1).

Picture 1.

In fact, it’s the exact opposite: no hard choices, no real alignment among different decisions; rather, top 10 lists of ‘pet projects’ for each business unit and function.

The practical outcome often is, as Peter Combo put it, “Lists enable everybody to come in, and as long as they get their bullet point on the list, they can go back to doing whatever they were doing before because they feel like they’ve been heard.”

Put differently, what gets on the lists has little impact on what people actually do.

Plan creation is appealing because it creates an illusion of control and predictability: here’s how the world will be, and as long as we do these things, everything will be fine. It’s possible to make plans that may or may not be executed over the next three to five years, without accountability for any of the content.

Decision-making is challenging because it requires facing uncertainty. It involves opening and closing possible courses of action, which have real-life consequences—and there are no guarantees that ‘everything will be fine,’ no matter what you do.

Most strategic planning is ineffective because it focuses on making plans, with little emphasis on decision-making—meaning no one truly has any ‘skin in the game.’

#2 No ‘Skin in the Game’

The simple reason why ‘strategic plans’ typically sit on executives’ bookshelves for 12 months is that no one has ‘skin in the game’ for what’s in them.

Typically, accountability applies only to what follows strategic planning: the annual budgeting process that results in resource allocations and the targets for the next year.

Since everyone knows this, the focus for years 2 to 5 (or however far out the ‘strategic plan’ goes) shifts away from genuine business needs and toward securing the best buffer and positioning for year 1 resource and target negotiations.

This increases the likelihood that strategic plans are ‘nonsensical’ from the start; while there is little to no accountability for their content, they can significantly affect an executive’s chances of hitting next year’s bonus—meaning funding their next kitchen renovation.

When you listen to finance professionals who preach the gospel of annual budgeting, you’re likely to hear arguments such as, ‘its purpose is to help implement the strategy.’

If that were the case, ask yourself: why are ‘Venetian blinds’ or ‘Hairy backs’ such common phenomena everyone jokes about? And why do only 30% of companies even tie budgets to their strategic plans?

The answer is simple: due to its characteristics, annual budgeting creates a view of the world that is inherently disconnected from reality. It is a tool to hit arbitrary targets based on projections from political negotiations, not to make decisions that effectively implement the strategy (provided one even exists in the first place).

Few companies link bonuses or other meaningful incentives to the numbers or plans outlined in strategic plans. However, as Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger point out, “incentives determine 99% of people’s behavior” (as cited in Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick).

Therefore, since there is ‘no skin in the game’ in strategic planning, it’s not surprising that, according to 70 years of research, the typical outcomes are equivalent to a drug that, in three out of four cases, either has no effect or makes the condition worse.

#3 Antithetical to Learning

“When facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

According to Mankins and Steele, “less than 15% of companies regularly compare actual results with strategic plans.”

Similar to annual budgeting, strategic planning processes, as Roger Martin points out, are typically unscientific: they lack the creation of hypotheses, the careful generation of tests, and fail to question the underlying assumptions.

It’s like a scientist developing a new drug who determines the outcome beforehand and does everything possible to make the test results match that outcome.

This inability to learn makes strategic planning particularly ineffective, as uncertainty is often highest with the most ‘strategic’ decisions and significantly high with the tactical decisions that implement those strategic choices.

This means the likelihood of ‘getting it right’ without testing your hypothesis is low, while the odds of such a ‘strategy’ (or whatever you call it) failing are high.

Creating a static plan under the assumption that it works, without the ability to test assumptions with data or revise decisions based on findings, makes it likely that companies will continue to pursue failing strategies rather than changing to better ones—even when real-life indicators suggest they should.

This happens because most strategic planning processes are calendar-based, meaning they are “on” only at certain times of the year (e.g., March to June) and have a cadence (time between planning cycles) that is often 12 months.

These characteristics either add significant delays to decision-making, decreasing agility, or force decisions to be made elsewhere, making planning ineffective.

As Roger Martin has said, “People have nutty corporate tendencies to do strategy in ‘September,’ and if I were truly bloody-minded and wanted to stomp all over a competitor, I would attack them the day after the board has approved the strategy.”

It is the structure of the process itself—set up by company executives—that makes strategic planning so often ineffective and disconnected from the real world, rather than an inherent ‘uselessness’ of planning or the skills of the people who are forced to work in it.

#4 Deterministic

Strategic choices are made under uncertainty and competition. What makes them ‘strategic’ is their scope—they impact the performance of the whole, rather than just a part of it. Such decisions typically have long lifecycles, requiring significant time to implement.

Consider, for example, a company shifting its ‘where-to-play’ focus from legacy products to sustainable ones. This shift would require changes to the product portfolio, which may have life cycles of four to five years, brand awareness efforts, and potentially investments in new production facilities that could take years to build.

Given the inherent uncertainty of the real world, it is impossible to predict precisely what will happen over the lifecycle of such decisions. Therefore, a deterministic approach to planning is bound to be ineffective for any truly strategic decision.

This is also true for deterministic financial estimates that extend over that time horizon, which are typically (though not necessarily should be) a core output of many strategic planning processes—such as projecting $1 billion in sales five years from now.

In reality, the likelihood that any static financial target will be hit (or to be more precise, that they should be hit) is virtually nonexistent due to the countless real-world factors in play. Similarly, major strategic decisions with high returns may, at best, have a high probability of success, but are never sure bets.

Despite this obvious reality, as McKinsey points out, inherent uncertainty is typically 1) ignored, 2) treated as an afterthought on page 149 of a 150-page deck, or 3) pretended to be addressed, rather than recognized as a key attribute and handled appropriately.

In other words, long-term deterministic planning operates on a fundamentally flawed assumption: that a company can accurately predict the future and, as long as it executes a series of planned actions, all desired outcomes will occur.

In reality, even if a company makes the best possible decisions and executes them flawlessly, the outcomes may differ significantly from expectations. Therefore, it’s ineffective to spend extensive time on deterministic plans with precise targets; instead, companies should focus on improving the ‘odds to win.’

#5 Siloed

Since strategy, by definition, is about the whole, and what is typically called ‘strategic planning’ happens at the business unit and function level, it is, therefore, an oxymoron. While it may involve planning, there is little ‘strategic’ about it, as it focuses more on individual parts than on the company as a whole.

This siloed approach inherently cannot maximize the performance of the entire organization, which is the core purpose of having a strategy. Instead, it often results in ‘spreading the peanut butter’ rather than making the big moves necessary to shift the company up the ‘power curve.’

Typical strategic planning lacks the capacity to produce a holistic and cohesive ‘strategic plan.’ Instead, it tends to yield separate business unit and functional strategies that may be only loosely connected.

Often, the extent of this ‘integration’ is simply adding up the financial projections from each unit to create a company-wide projection. Missing from this approach is an understanding of how the underlying choices fit and reinforce each other.

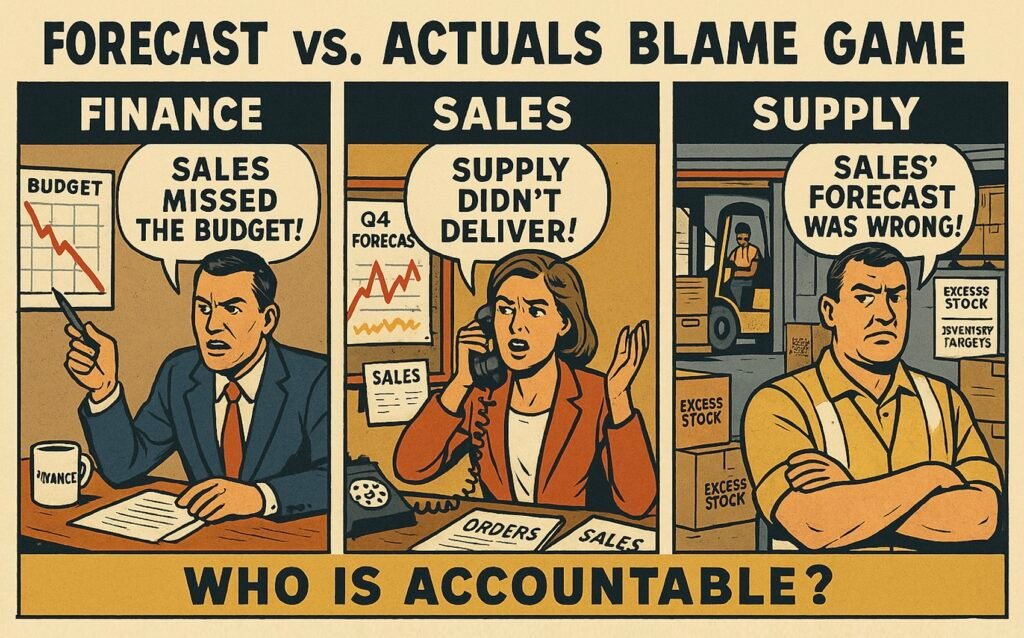

Moreover, the way strategic planning is performed doesn’t acknowledge the fact that, to optimize overall performance, some parts of the business may need to perform worse than they did the previous year—or even be sold off or shut down altogether.

As McKinsey notes, one area where companies struggle most when attempting to transform their business is being reluctant to cannibalize existing sales, even when that is often required to maximize the odds of winning.

When each part of the business conducts strategic planning in isolation, it is unlikely that any unit will propose a strategy that reduces its own resources or suggests shutting down. Silos protect their own interests, which means that without a unifying strategy, the organization’s overall goals are unlikely prioritized.

Further, as Mankins and Steele note, the concept of planning in business or functional silos goes against how most companies typically make decisions: issue by issue. There is a simple reason for this: most major decisions have cross-functional interdependencies, and at the very least, all major resources are linked to each other through financial resource allocations.

Conclusion

What most companies call ‘strategic planning’ is fundamentally ineffective for one simple reason: it fails to produce a useful output.

If the output is a plan, as it is commonly understood, that plan will inevitably become obsolete, as it is too detailed and too infrequently (if ever) updated, and therefore following it will hinder performance.

If the output is intended to be better decisions, whether ‘strategic’ or ‘tactical,’ the only option is to make them once a year, which either adds considerable delay or forces decision-making elsewhere.

Some argue that even if the plan cannot be followed and no decisions are made, it is still ‘useful’ to conduct a deep dive into the business. While this may be true, it also suggests that for the rest of the year, when real decisions are made, there is insufficient knowledge about what is happening in the business.

While such planning may be a useful exercise, it serves that purpose only if the company is operating ineffectively for the rest of the year. There is likely more potential in addressing that root cause than in understanding ‘what’s going on in the business’ during a few months of the year.

The main reason strategic planning lacks a useful output is that there is no ‘skin in the game’ to ensure one. For the output to matter, there must be accountability for it at the very top.

As soon as such accountability is attached, the need for the capability to learn and adjust based on real-world factors becomes apparent.

To do this effectively, strategic planning must move beyond black-and-white (0% or 100%) thinking. To learn effectively and make profitable bets, one must start using ‘in-between numbers’ by incorporating probabilities into the strategic planning process.

Finally, improving the whole organization requires looking at the whole rather than focusing solely on individual parts. Planning that deals with overall organizational performance must include a mechanism to plan for the entire organization and the capability to make decisions that may ‘hurt’ certain parts for the benefit of the whole.

Whenever even one of these conditions is not met—1) the purpose is not to make decisions, 2) there is no ‘skin in the game’ for the output at the top of the organization, 3) there is no mechanism to test and update the plans, 4) planning is deterministic in a probabilistic world, or 5) focus is on the parts rather than the whole—it is not surprising that the effect on performance is negligible or even negative; in fact, it’s exactly what you would expect.

Practical insights

- Plans do not impact performance; decisions do.

- Strategic plans sit on bookshelves since there is ‘no skin in the game’ for them.

- Static plans are inherently unscientific and antithetical to learning.

- Effective long-term planning requires the use of probabilities.

- ‘Strategic’ planning conducted for the parts of the whole is an oxymoron.