Introduction

The most common arguments against planning in companies are based on misconceptions or strawmen. This doesn’t mean that most people are naïve or ‘just don’t get it,’ but rather that these views are a natural consequence of ‘the most common practices,’ such as the annual budgeting process, annual ‘strategic’ planning, or even many ‘rolling forecasting’ processes.

This is understandable, given that most people don’t have a say in the planning systems they are required to work within, while those who do often recognize that changing these systems is both risky and challenging—making it easier to stick to (and rationalize) the status quo.

For anyone committed to improving performance and willing to confront these challenges, it’s crucial to recognize that some arguments against planning reflect more of a mindset rooted in ‘this is how we’ve always done it’ than a reflection of how things must be.

#1 Purpose Is to Create a Plan

The most common misconception is to think of planning and plans as the same.

While planning does involve creating plans, they should be a means to an end—not the end itself. By definition, plans are coordinated decisions to achieve specific targets under specific assumptions.

Plans become invalid when assumptions change (as they inevitably do), when decisions aren’t executed, when new decisions are made, or when the level of target difficulty changes.

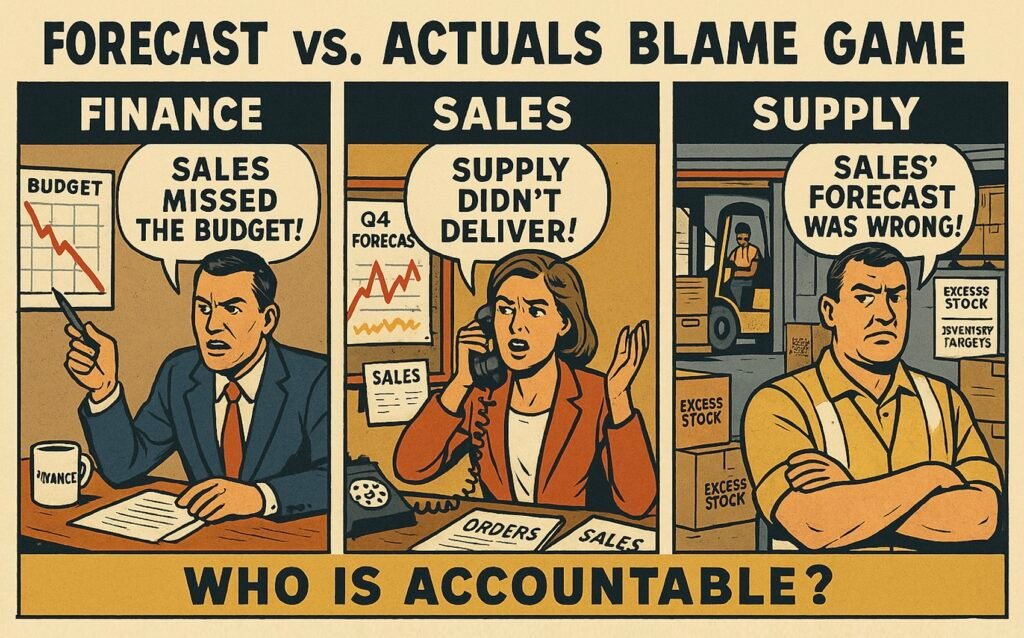

This means the numbers in the plans also become invalid. While many do indeed abandon the original plans (e.g., don’t invest in marketing), they inexplicably hold on to the numerical outcomes (like sales of $1 billion) of such plans, which are no longer grounded in the real world.

The assumptions have changed (e.g., the market is declining instead of rising), decisions are different or even reversed (e.g., marketing cost cuts instead of marketing investments), and a target as realistic and challenging as the original $1 billion would now be something else. Sticking to the original target in changed circumstances arbitrarily alters the level of difficulty.

Treating plans as the purpose of planning is an unnecessary, self-imposed constraint, and clinging to arbitrary static numbers is irrational. There is no logical reason for this other than ‘that’s how we’ve always done it,’ which makes it hard to change—perhaps the only valid reason to stick to the status quo.

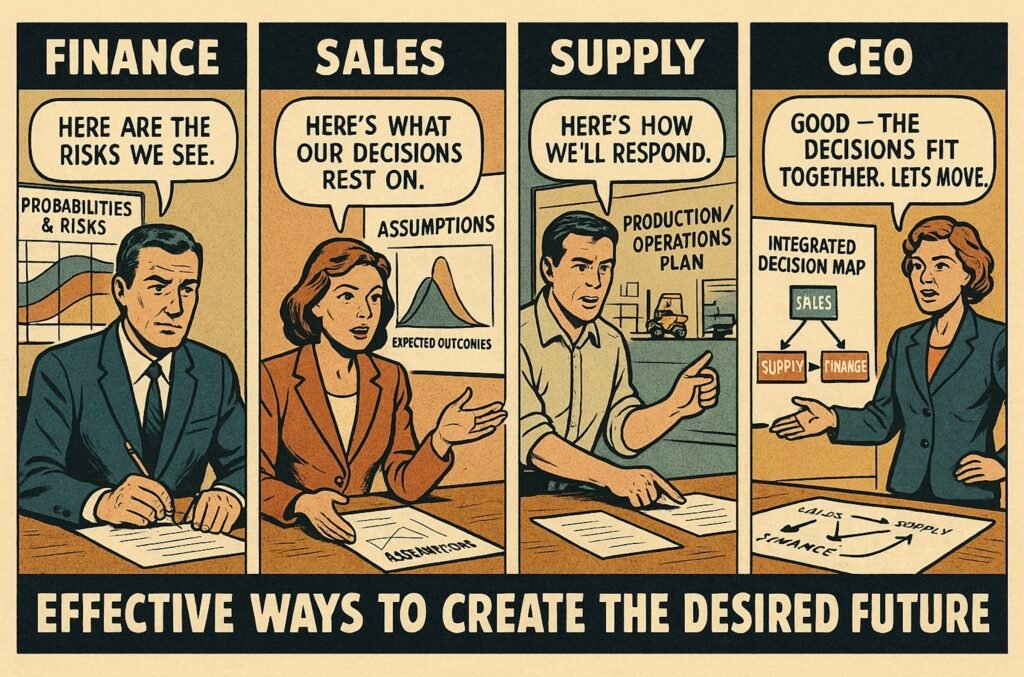

A more effective purpose of planning is to make better decisions. Though this may initially seem like an academic distinction, it has profound practical implications: plans don’t impact performance—decisions do.

When planning is reduced to ‘plan creation,’ it often results in ‘reviewing the numbers’ (as in many ‘rolling forecasting’ processes) or ‘listing initiatives’ (as in annual strategic planning), both of which have little to no impact on how the company is actually performing.

Meanwhile, the real decisions are made elsewhere, based on ‘something else.’

The opposite approach is equally harmful: treating the achievement of plans (or at least hitting the figures in them) as the highest priority (as in annual budgeting), regardless of whether the assumptions, decisions, or targets remain valid in reality.

The critical difference between simply ‘creating plans’ and planning effectively is that plans are connected to reality and are revised—new decisions are made, and assumptions are updated—when reality changes.

#2 ‘It’s Useless to Plan That Far’

Odds are you’ve heard this one, or maybe even said it yourself. What constitutes ‘that far’ may vary, but for many, it refers to a timeframe that’s further than what feels ‘relatively predictable’ to them, like the next six months.

This misconception arises from misunderstanding the purpose of planning (misconception #1).

While it may indeed be ‘useless’ to create static plans ‘that far,’ there’s no limit to how far it can be both useful and effective to plan when the goal is to make better decisions.

This stems from a fundamental fact: regardless of uncertainty, all decisions have consequences and commitments that extend into the future.

Consider the decision to launch a new product. It may take 1 to 2 months to make the decision, 6 to 12 months to develop the product, and 3 to 4 years for it to generate revenue in the portfolio. In other words, it has a decision lifecycle of 4 to 5 years.

While it’s impossible to predict precisely what will happen over the next four to five years, it’s always possible to improve the odds that these decisions will succeed within that time horizon.

That is, in fact, all one can do. Rationalizing that ‘it’s useless to plan that far’ means failing to understand the relevant impacts, interdependencies, risks, or opportunities associated with different decisions, which ultimately lowers ‘the odds to win’ over time.

Put simply, anyone responsible for a company’s future performance isn’t doing their job properly when they impose artificial limits on how far it is useful to plan.

#3 It’s About the Future

As a corollary to misconceptions #1 and #2, it is quite common, even for high-level executives, to think of planning as something that focuses on the future and is, therefore, the opposite of ‘execution,’ which happens here and now.

While planning indeed entails thinking about the future, it is not about the future. It is not about imagining what one might do a year, two years, or three years from now, and it is certainly not a tradeoff for executing well here and now.

As perfectly summarized in Alan Lakein’s definition, planning is how we can better understand the future implications and interdependencies of our current actions and, therefore, choose better actions here and now, including not deciding.

The reason many get confused about this is that what is often called planning in companies is, in fact, merely ‘dreaming about the future,’ with little to no impact on performance or accountability for what goes into those plans or what happens as a consequence.

People create static multiyear plans, describing in too much detail which projects or actions they might do in years two or three. As the world is uncertain, and since many of these details have little to no relevance to what you need to do now, that type of planning is indeed largely a waste of time and a tradeoff against great execution here and now.

So, if that is your understanding of planning, you’re right to do as little of it as possible. However, if that is the reason why you stop planning or reduce the time spent on it to the bare minimum, the odds are that you’re also going to make some really dumb decisions here and now.

The simple reason is that, regardless of how much or little you may plan, all business decisions with significant impacts on the business have long-lasting effects, commitments, interdependencies, and trade-offs.

‘Executing’ blindly here and now, without understanding those impacts and interdependencies, will result in being efficient at something that shouldn’t be done in the first place or missing opportunities with ‘better odds of winning.’

The irony is that this leads to more ‘surprises’ and firefights, which increases the illusion that performance is all about ‘execution’—the adrenaline rush of dealing with the half self-created crisis of the day.

#4 The Higher Cadence, the Higher the Workload

All other things equal, this might be true—but it’s also an unnecessary self-imposed restriction.

A common counterargument against more frequent planning cycles (e.g., moving away from an annual cadence) is that the workload will explode: “We can’t budget 12 times a year.”

Right, it’s indeed impossible to budget (perform the same rain dance performed during annual budgeting) 12 times a year. What’s overlooked, though, is that much of that effort is unnecessary and even counterproductive to performance.

This misconception is another direct result of misunderstanding the purpose of planning. Much of the workload in once-a-year planning processes is due to their annual nature.

First, because of the long cadence, the previous plan is either largely obsolete (as in strategic planning) or the time horizon is already gone (as in annual budgeting). This means planning must start from scratch instead of being based on managing meaningful exceptions.

Second, because everyone knows it’s impossible to capture reality in a static annual plan, creating it becomes more of a political negotiation than an attempt to model the business and determine what to do about it. Much of the time and effort is spent building hidden siloed buffers to deal with uncertainty and negotiating over who gets left with the shortest straw, rather than making meaningful decisions.

Third, as a corollary to the first and second points, the level of detail is often excessive. Whoever has the most information can leverage it in the negotiation—not to add relevant input, but to appear more knowledgeable or to question someone else’s expertise. You can always ask for ‘more information’ or say, ‘how about this,’ when in reality, the reason is that you don’t like how the current facts affect your negotiation position. Much of this adds little value to company performance.

Furthermore, as it’s often either the first time that time horizon is examined or so long since the last review people feel a need for a ‘deep dive’ into the business to feel comfortable that they understand all necessary nuances.

It is beyond the scope of this article to list all the reasons, but the practical consequence is this: when planning is a continuous process, with an appropriate cadence, the irony is that the workload may in fact decrease.

#5 Decreases Agility

Ask a room full of people who has heard this as an argument against planning, and the odds are 110% of hands will go up. With the risk of sounding repetitive, this is yet another common symptom of ‘plan creation’ instead of decision-making.

Creating a static plan and attempting to follow it when real-world conditions change does, indeed, decrease agility. Which is like discovering that banging your head against a wall makes it hurt. Who would have thought!

Here’s a radical suggestion: how about not doing that? Where did you get the idea it was a good approach to do either, anyway?

There’s no reason why planning would decrease agility.

In fact, according to McKinsey partner Aaron De Smet, somewhat counterintuitively, a certain level of structure may actually enable you to move faster. Without it, people are less likely to align and commit to executing decisions.

When planning does decrease agility, it’s due to an unnecessarily long, arbitrary cadence. The most common counterargument against fixing this is: “We can’t budget 12 times a year.” (misconception #4.)

In other words, if you think planning decreases agility, it’s either a skill issue (you don’t know how to plan), or you’re executing aimlessly without having any understanding of the consequences of your decisions (which also means it’s a skill issue).

No matter how you look at it; the issue is you, not some inherent flaw of planning.

#6 Closer to Real-Time, The Better

This is often promoted by software vendors for a simple reason: it’s a great selling point. It aligns with a common frustration people have with planning: plans become obsolete, and there’s often too long a delay in making the right decisions.

So, what’s wrong with this? Sometimes nothing, but often a lot. Some decisions do benefit from real-time information and decision-making, but many—especially major ones—don’t, which is often missed in sales pitches.

This happens because agility is confused with time to make a decision. It’s assumed that the faster decisions are made – the higher the agility. But this isn’t true.

Consider the earlier example of launching new products.

The decision lifecycle was 4 to 5 years, while the time to make the decision was 1 to 2 months. Even if the decision time were cut to zero, the lifecycle would essentially remain the same—unless the time to develop the products and the time to generate the same revenue were also reduced radically. Since that is rarely possible, it would still take the company 4 to 5 years to renew its product portfolio, regardless of decision speed.

What often drives this confusion is that while speeding up a single decision can provide benefits (e.g., addressing an urgent customer need), these benefits don’t scale at the portfolio or company level.

In contrast, too frequent changes can confuse the organization. For example, R&D would constantly pivot, unable to make progress if decisions about which products to launch were updated daily.

And even if the information would be available in real-time, decision-making often requires understanding, alignment, and commitment of several stakeholders, which is often dictated by other factors than the availability of information.

Real-time information is useful for small, low-impact operational decisions, like assigning availability to a sales order or stocking shelves, but it’s often useless—or even harmful—for most major decisions, like strategic where-to-play, how-to-win choices, or tactical decisions that implement such choices, like launching new products.

Conclusion

Depending on the viewpoint, the most common arguments against planning are either strawmen or misconceptions, and many of them are caused by what is understood as the purpose of planning, and the only reason for that is ‘this is how’ve always done it.’

When the purpose is simply to ‘create a plan,’ it may indeed seem ‘useless to plan that far,’ a higher cadence may appear to increase workload, planning might seem to be about the future and to decrease agility, and a closer-to-real-time approach might appear better.

However, plans alone have no impact on company performance—only decisions do.

Consequently, ‘plan creation’ often becomes disconnected from real decision-making, as real-world assumptions change, new decisions are made, and some decisions in plans are not executed.

When the purpose of planning is seen as making better decisions, there are no limits on how far it is useful to plan, as it depends on the characteristics of the decisions being made.

A higher planning cadence can even reduce workload, as the focus shifts from capturing a probabilistic reality in a static plan (an impossible task) to improving business performance here and now, based on relevant information and by updating only what has changed.

When the planning cadence aligns with real decisions, it does not reduce agility; in fact, it can, somewhat counterintuitively, increase it by improving alignment and commitment among stakeholders and reducing decision churn.

Aligning planning practices with decision characteristics also prevents falling victim to software vendors’ claims that real-time planning is necessary for good decision-making. In reality, for most major decisions, real-time planning is at best unnecessary and, at worst, actively harmful.

The overall lesson is this: before declaring that ‘planning is useless’ because of ‘x’ and jumping on board with the latest concept or system—the home-shopping network equivalent of a revolutionary exercise gadget or diet program—ensure it’s not your own misconceptions or strawman arguments leading to that conclusion.

It will help you avoid making some really dumb decisions here and now that will hurt performance, and it can save you millions of dollars and years of wasted effort in trying to solve a problems that didn’t exist in the first place.

Practical insights

- The purpose of planning is to make better decisions.

- There is no limit to how far it is useful to plan.

- Planning is about what you can do better here and now.

- Higher cadence can, ironically, lead to a smaller workload.

- If your planning decreases agility, you’re doing it wrong.

- Real-time information is often not needed and can even be harmful.