Introduction

The flaws in common planning processes, such as annual budgeting or strategic planning, are well known. As a result, many companies are in the process of transforming their planning practices, have already attempted such changes, or are planning to do so.

However, many organizations that have tried to make significant changes to their planning practices have failed. Those currently undertaking or planning such transformations are also likely to fail, as they fall victim to one or more common pitfalls of planning transformations:

- The level of ambition is too low.

- The business benefits are not clear.

- The business owner isn’t the owner.

- Incentives remain unchanged.

- Impacts on stakeholders’ power are not adequately addressed.

- Inadequate resourcing.

- Technology is thought of as a solution, not as an amplifier.

Get any one of these wrong, and the odds are that the ‘planning transformation’ will end up as a mechanical update that doesn’t improve the company’s performance.

This turns the planning process into an elaborate numbers and PowerPoint exercise, leaving stakeholders wondering, ‘What’s the point?’ and many concluding that ‘planning is a waste of time.’

However, by adequately addressing these issues, companies can genuinely transform the way they make decisions, eliminate major flaws and drawbacks of traditional approaches, and significantly improve long-term performance.

#1 The Level of Ambition Is Too Low

The biggest reason planning ‘transformations’ fail is that they are not treated as transformations in the first place.

In other words, while there is often an expectation of major benefits (although these are often not well articulated, see #2), the assumption is that great things will be achieved without significant changes how decisions are made.

A transformation, by definition, is a major change in ways of working, typically aimed at achieving significant benefits.

Aspiring to major benefits from planning implementation requires major changes in how decisions are made. This, in turn, demands significant changes in behavior, incentives, and even the organizational structure.

In other words, expecting major benefits from new planning practices always involves a major transformation, and planning transformation is never just about implementing a new planning process or a system.

For example, a common mistake occurs when frustration with annual budgeting leads to a focus on technical issues, such as ‘it’s too rigid,’ followed by the launch of a ‘rolling forecasting’ project to enable ‘dynamic resource allocations.’

The mistake here is assuming the problem lies solely in technical aspects like planning only once a year or sticking to the time-horizon of a calendar year. In reality, these are merely symptoms of deeper issues, such as executives’ short-term thinking and their desire for the illusion of control.

As Bjarte Bogsnes explains in his book “This is Beyond Budgeting,” moving to rolling forecasting also requires changes in leadership practices.

More generally, a common error is focusing on technicalities like processes or systems while ignoring the root causes behind why the existing processes and systems are in place.

To achieve real benefits, major planning transformations must always examine their implications for leadership practices, incentives, and even organizational structure.

Put simply, there is no such thing as a ‘planning transformation’ in the strict sense of changing ‘only’ planning. This approach is doomed to fail because it doesn’t go far enough to change behavior.

Therefore, making major changes to planning practices should always be part of a broader ambition to fundamentally alter how certain types of decisions are made—or, in the context of the entire organization, how the company is steered.

#2 The Business Benefits Are Not Clear

This is the biggest difference between theory and practice. In theory, everyone ‘knows’ this; in practice, in most cases, the business benefits are not clear.

According to McKinsey, understanding why the change is needed, and how it will help the company to move to right direction can double or triple its changes to outperform their competition.

Common ‘business benefits’ for planning transformations often focus on technicalities like “to implement a system or process” or secondhand ‘benefits’ like “improve alignment, forecasting, or automate something.”

The problem is that these will always lose to real business benefits like increasing sales or lowering costs. This means the planning transformation doesn’t even get a chance to work, as it won’t ever be a high enough priority to warrant the required effort.

There will always be an infinite amount of ‘more important’ things that deliver real business benefits. One reason people are often reluctant to describe the benefits of planning transformations in terms of real business outcomes is that they cannot be sure what those are.

How can you really determine how much sales are increased because of changes in how planning is done? There could be a million reasons for it.

This is true—it is often difficult, or even impossible, to conclusively determine the precise impacts of planning transformations on real business benefits, as the causal relationships are complicated and often delayed.

This should not, however, be a reason to avoid clearly describing the real business benefits, such as increased sales, lower costs, or a higher share price. Doing so is vital, even if the causal links cannot be 100% proven, because it enables discussion and alignment among stakeholders on how planning will deliver real value.

For example, if the ‘benefit’ is described as implementing ‘rolling forecasting,’ many will assume this just means setting up new meetings with new templates. They fail to see why this would also require changes to incentives, organizational structures, and leadership behaviors. That seems excessive!

However, if the benefits are stated as something like ‘higher sales growth,’ the roles are reversed.

“How does setting up some new meetings and templates result in higher sales growth?”

Once you start digging deeper into that, you’re more likely to gain a realistic understanding of what needs to change and why. For instance, annual bonus targets set in stone must also cover the rolling forecasting period and stay relevant to that time horizon.

Otherwise, what’s the point of having a rolling forecast that extends so far?

#3 The Business Owner Isn’t the Owner

As a corollary to #1 and #2, initiatives to change the way planning is done, are often delegated down in the organization. And when the ambition is low, and the business benefits are unclear, this makes sense of course.

Why should executives with real power be owners of a planning transformation? That’s about creating some meetings and new templates, right? They have much bigger issues to deal with like how to run the company.

Having the ownership being delegated down in the organization is one practical consequence of there being ‘million more important things’ that create ‘real business benefits’ as mentioned earlier.

This however leads to a downward spiral or the odds that the planning transformation will generate any meaningful benefits because it results into:

- The business owner is less likely to change their behavior.

- The business owner won’t provide sufficient support.

- There will be ‘dual accountability’ of the results.

The practical consequence will be that the business is ran (how decisions are made) will remain mostly the same, while the ‘planning transformation’ will be reduced to mechanical exercise that will be added ‘on top’ of how real decisions are made.

Major issue is that in order to make meaningful changes, it is often necessary that leaders change the way they behave. And unless they are the owners of the initiatives that attempt to do that they are less likely to do that, as the lack of ownership is a sign in itself that the initiative is ‘not important enough,’ for the ownership to be at the top. And no one is going to change their behavior in meaningful way for something that isn’t ‘important.’

The low priority will by definition translate into low amount of time and resources allocated to the initiative, which of course makes sense. Why would anyone pay attention or allocate resources to initiatives that are not a priority?

It also means that it is unlikely that the holistic changes (such as changes in incentives and organization structure) will ever be made, as it is not in the power of the owner of the planning transformation to make such changes.

Having the ownership low in the organization means also that there is either no expectation of high benefits or there is a dual accountability of the benefits. Take for example rolling forecasting.

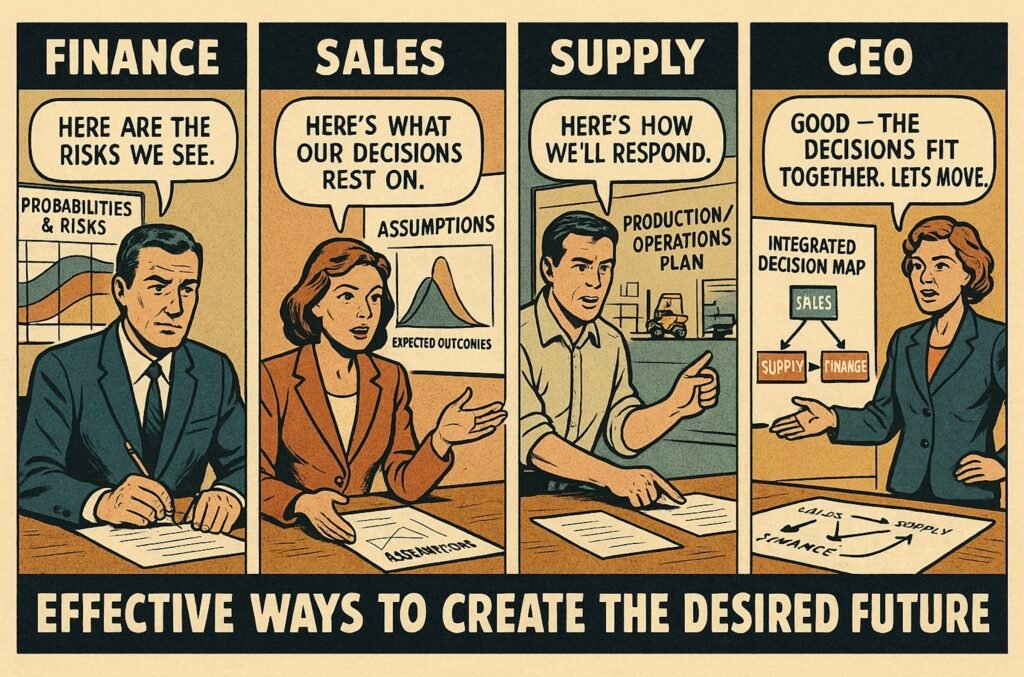

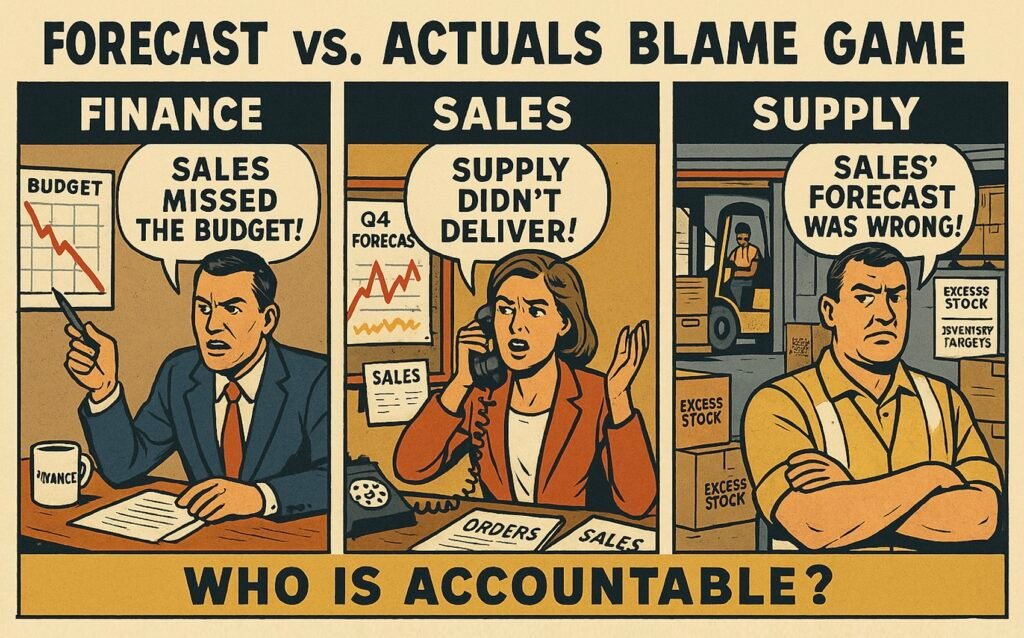

Sales is accountable of sales but rolling forecasting projects are often driven by finance or operations. Neither of them have accountability of what will be sold.

What is the value of a more “effective” financial forecast if sales is going to sell something else, and the supply chain is going to produce and deliver something else?

Or what is the value of a more “effective” sales forecast if the commercial decisions made in sales don’t reflect it, and all resource allocation decisions are based on the financial forecast?

When significant benefits are pursued in silos, the initiatives end up being more about “improving the dance” than “impacting the weather.”

In the latter case—say, the change is delegated down the organization to an FP&A team or a supply chain team—neither has the authority to get all required stakeholders committed to a common cause.

Even if team members have significant personal influence, they are unable to change incentives (e.g., how the sales team’s bonuses are structured) or address the repercussions of changes in power (e.g., sales’ ability to influence product or production decisions through personal relationships).

The only role with natural accountability for cross-functional results, the power to change necessary incentives, and the ability to manage changes in power dynamics is the CEO. To avoid conflicts or a lack of accountability, she must be the owner of any major planning transformation aimed at achieving major company level benefits.

#4 Incentives Remain Unchanged

This is a natural consequence of #1, #2, and #3. In the absence of these three, there is neither a reason nor the required support from the top to even consider this.

According to McKinsey, transformation initiatives that address impacts to target setting are 50% more likely to succeed.

However, failing to revise incentives, at best, decreases the odds of achieving real behavior change and, at worst, makes it impossible.

Consider, for example, implementing some form of ‘rolling forecasting.’ Imagine that all the technical changes, such as implementing new software and a state-of-the-art planning process, were successfully completed.

This means the company would have the technical capability to create an always-up-to-date forecast—for instance, for the next 18 months—and even dynamically allocate resources over that time horizon based on the latest information.

However, if all incentives remain tied to a shrinking calendar year, behaviors such as focusing on the short term, sandbagging estimations, and fully using existing budgets by the end of the year would likely persist.

Consequently, the benefits would be minimal, as decisions about how resources are allocated or used wouldn’t change significantly from prior practices. Everyone would still be playing the annual budgeting game: optimizing their own chances of meeting calendar year targets.

While there may be many potential benefits for the company in adopting a rolling 18-month view—such as considering the longer-term impacts of resource allocations, releasing excessive resources for more productive uses, or improving flexibility—from an individual’s perspective, doing so would only diminish the odds of achieving personal targets.

In other words, while technical changes can create the possibility for better decision-making, revising incentives is often required to align individual interests with the new opportunities.

For instance, in the case of ‘dynamic resource allocations,’ to incentivize individuals to account for the long-term impacts of their decisions, their incentives should span several years rather than being restricted to a calendar year.

Furthermore, as uncertainty increases over the long term, incentives should remain relevant across that horizon or they will be counterproductive.

This means traditional static point estimates are unlikely to work. Instead, the company should consider either adopting dynamic targets—such as market share instead of absolute revenue—or incorporating target revisions into the dynamic process itself.

The exact methods for changing target setting may vary, but the likelihood of significant behavioral change is slim without any modifications to incentives.

#5 Impacts on Stakeholders’ Power Are Not Adequately Addressed

What is the number one thing that drives people’s behaviors in business? Creating shareholder value? What’s good for the customer? Sales and profitability?

None of those.

While these are perfectly good second- or third-priority drivers, the most important driver is always: “What’s in it for me?”

Although incentives like annual bonuses are one part of this equation, another—possibly even bigger—factor is the impact on an individual’s power within the organization: their importance, decision-making authority, ability to influence outcomes, and potential to advance their career.

It’s great if creating shareholder value, being good for the customer, or increasing sales and profitability aligns with an individual’s self-interest, as it often does. But that’s not always the case.

One thing all transformations have in common is their effect on power dynamics, as by definition, a transformation represents a major change in ways of working.

Even if there is a strong case for the change, with clear business benefits and a dedicated business owner driving it, the planning transformation initiative must address its impact on stakeholders’ power.

This is what will ultimately drive commitment or resistance within the organization.

For some, the change will have a positive impact, and they will support it—whether or not they fully believe in the business benefits. For others, the impact will be negative, and they will resist it—regardless of whether they believe in the business benefits.

Most stakeholders, however, will be uncertain about the impact on their power and, as a result, will be apprehensive. Because of this, they may not openly resist the change but will be far from enthusiastic about it.

For some, it’s enough to go through the changes and demonstrate the benefits, but even this requires time and effort—both from the project team and the organization.

However, no matter how much time and effort is spent, major changes will never be net positive for all stakeholders. This is because improving the performance of the whole is not simply the sum of its parts.

To maximize the whole, some parts will inevitably suffer.

This means that not everyone will be happy. Some will leave on their own and need to be replaced. For others, it may be possible to offer alternative forms of compensation, but there will likely be a small number of people who need to be let go.

The impact on stakeholders’ power is one of the reasons why ownership of the planning transformation must rest with the highest accountable person affected by these changes.

This individual must not only be capable but also willing—committed enough—to let go of some people who may even be considered “high performers” under the old system.

Consider, for example, a ‘rolling forecasting’ initiative. In the absence of a structured planning process, sales teams often communicate directly with product management or operations to influence production and product decisions.

A practical consequence of implementing a cross-functional, dynamic resource allocation process is that the sales team’s ability to influence these decisions diminishes.

Decisions will no longer depend as much on individual relationships—many of which may have been cultivated over years or even decades—but instead rely on a structured process that evaluates impacts and possibilities holistically and with less bias.

While this change is arguably better from the company’s perspective, it may be seen as much worse by an individual “old school” sales representative who has built a successful career under the previous system.

#6 Inadequate Resourcing

Everyone always complains about resources, so it can be difficult to know when this is a real issue and when it’s an excuse.

However, given that companies tend to have fewer resources than they would like for their initiatives, and considering that planning transformations often suffer from low ambition, unclear business benefits, and low ownership within the organization, the odds are that such initiatives are more often under- than over-resourced.

This is supported by research.

Although not specific to planning transformations, McKinsey reports that most companies assign only 2% of their employees to transformations, which leads to a negative average impact on total returns to shareholders (TSR).

However, when employee involvement exceeds 7% of stakeholders, the odds of achieving positive impacts on TSR are twice as high compared to industry benchmarks. McKinsey also concludes that increasing involvement up to 30% of the workforce can produce a significant positive impact on TSR.

Of course, these principles apply only to major transformations where the expectation is to make a fundamental change in how the company operates—not merely to ‘implement a new planning system or process’ or tweak existing ones.

In addition to low ambition and unclear benefits, a major reason why planning transformations are often inadequately resourced lies in a lack of understanding of the work required.

That happens for two reasons: failure to understand all the elements involved in making the change and lack of a realistic view of the current ‘as-is’ situation.

A simple example of the former is defining the new way of working—for instance, the process steps, roles and responsibilities, meetings, and templates. However, drafting these technicalities requires vastly less effort than gaining commitment to the change and driving behavioral transformation.

A knowledgeable person or small team could define these elements in a matter of days, add a similar amount of time for ‘education,’ and call it done.

However, involving stakeholders widely can take weeks or months because it requires building alignment on what is being done and why, providing training on basic skills, and resolving differing viewpoints.

Not involving people may create an illusion of speed, as technical outputs like process charts can be produced quickly. However, involving people from the beginning will ultimately be faster.

The time spent on alignment and resolving disagreements is unavoidable and will need to happen before real benefits are realized. Attempting to do this with a forced, technical model will be exponentially harder—if not impossible.

The time and effort required also depend on the ‘as-is’ state, which is why general timelines, such as “six months to major benefits,” can not only be misleading but also lead to inadequate resourcing.

It’s the same as the work required to achieve 10% or 20% body fat being significantly different depending on whether your starting point is 30% or 40%. Going from 30% to 20% is a much easier and faster change than going from 40% to 10%.

The resources required depend heavily on what is considered success and the starting point. Being unclear about the business benefits and oblivious to the starting point will likely result in gross underestimation of the resources required, leading to almost certain failure.

#7 Technology Is Thought of as a Solution, Not as an Amplifier

Here’s the problem: while technology does solve some problems, it never solves the root causes why real benefits are not achieved. Achieving real benefits always requires a change in how decisions are made, which requires change in behavior.

People don’t use probabilities in planning because they don’t have a system that can handle them. They don’t use them because deterministic numbers are more familiar, more comforting, easier to use and enable more manipulation.

A consequence of that is that when focusing on technology, it’s likely that you’re focusing on secondary problems, some of which could be eliminated altogether.

For example, technology can solve a problem to process a large amount of data. And while that may indeed be needed and beneficial, while focused on improving the processing of large amount of data, you are likely to miss that a lot of that data is not helping to improve decision-making.

At first it may seem like the problem is ‘to be able to budget 12-times a year’ and that requires dealing with 12-times the data than in annual budgeting.

In reality, however, 90% of the level of details used in traditional budgeting may be inconsequential to making good dynamic resource allocation decisions, and the keeping the plans up to date takes only 10% of the work compared to building them from scratch.

It other words, the real problem is not how to process 12-times the data in annual budgeting, but how people can plan more effectively with far less data by removing everything that is not relevant to making great decisions.

Technology can support the behavioral and mindset change and amplify its usefulness, however it doesn’t solve the problem how to make that change. It solves the problem how to process large amounts of data efficiently, or how to make exception-based adjustments to existing plans.

Technology can also create multiple scenarios, maybe even real-time. And while that may also be beneficial, when focusing on that, you might miss that all those scenarios are based very precise deterministic numbers, that in turn are based on historical patterns, that are assumed to be relevant in the future.

While in reality, it may be more beneficial to describe the future with probabilities, and ‘logical stories,’ rather than precise predictions based on historical patterns.

How can you ensure the right level of focus on technology?

First, make sure the ambition is high enough and the business benefits are clear and aligned (as discussed in #1 and #2), and dig into the root-cause, how to make that happen. This is so you don’t end up automating something that shouldn’t exist in the first place.

Second, list the decisions the change will impact and identify its effects on the main stakeholders (as discussed in #5). Technology should appear on this list in two capacities:

- Making some stakeholders’ lives easier or increasing their power and influence.

- Reducing the decision-making power or influence of others.

Do not proceed with technological changes where there is no clear plan how to manage the ‘social side of change’ of the latter.

This includes avoiding changes that require commitment from other functions (where you lack the power to secure that commitment) or changes to incentives unless you’re willing-and able-to modify those incentives.

For example, do not proceed with a system to ‘automate forecasting,’ if that reduces the power of sales to impact product and operations decisions, because you’ll only end up wondering why the ‘sales are not on board,’ and doing something other than what is in the forecast.

Conclusion

Planning in most companies is stuck in the 1970s—or, as some might argue, even the 1920s. This presents a tremendous opportunity to modernize planning practices, particularly by moving away from traditional annual budgeting and once-a-year ‘strategic planning’ conducted business unit by business unit.

Making such changes, however, is always a major transformation by definition. The goal is to fundamentally alter planning processes with the expectation of achieving significant business benefits.

As with any transformation, many common pitfalls apply to the modernization of planning practices. The most significant of these is setting the level of ambition too low, followed by unclear or overly technical business benefits, and delegated ownership that is pushed too far down the organization.

These three pitfalls alone are enough to ensure that no major business benefits are realized, no matter what other efforts are made.

Even if these challenges are avoided, companies must still address the impacts on incentives, stakeholders’ power dynamics, and develop a realistic understanding of the resources required to implement the change.

This includes not only grasping the intricate nature of the work involved but also accounting for the organization’s current as-is state.

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ timeline for achieving great results. Success depends always on what ‘business benefits means to the company and where they are starting from.

If all of these factors are adequately considered, the likelihood of falling into the technology bias trap is low. However, a technology bias can serve as a reliable indicator that not all of the above have been properly addressed.

Transforming planning processes is never an IT project or a simple technology change. If it is treated as such, it is a clear sign that the expected business benefits will be marginal.

Finally, reaching significant benefits always depends on many factors beyond these pitfalls, especially the quality of the execution of the changes. Being aware of these pitfalls is not enough on its own.

However, the opposite is equally true. No matter how great the team is or how high the quality of the execution, failing to address these pitfalls will guarantee poor results.

It is similar to fitness. Achieving great results is not only about having the right exercise and dieting fundamentals, but failing to get those fundamentals right will guarantee that, no matter how dedicated the effort or how high the quality of the execution, the results will remain modest.

Practical insights

- Set a sufficiently high level of ambition.

- Clearly articulate the business benefits.

- Ensure the business owner truly owns the initiative.

- Revise incentives to align with the desired new behaviors.

- Address the impacts on stakeholders’ power dynamics.

- Align resources with the level of ambition.

- Use technology as an amplifier, not the solution.