Introduction

What’s common to most organizations at the beginning of the year?

- They are still holding on to the annual budget.

- The annual budget no longer makes sense to ‘hit.’

In other words, for most, there is a significant potential to improve performance by forgetting the budget and focusing on making the best possible decisions here and now.

There are several reasons why companies should let go of the annual budget.

For instance:

- Many didn’t finish the previous year as assumed in the budget.

- Even if they did, they likely made ‘stupid’ decisions to accomplish that.

- There was no solid business logic behind the budget.

- Even if there was, it wasn’t aligned with the strategy.

- Even if it was, odds are it’s already obsolete.

- Even if it wasn’t, the monthly breakdown doesn’t reflect great performance.

- Shareholders care more about real performance than ‘hitting the budget.’

- Small improvements in short-term lead to a big difference in the long-term.

- The ‘stability’ of the budget doesn’t benefit customers or employees.

Holding on to the budget is like an alcoholic being in denial about having a drinking problem. In both cases, the faster the problem is acknowledged, the faster the recovery can begin.

Case Study

Consider the case of a food and beverage company focused on the premium organic snacks market, offering high-quality, sustainable, and innovative products.

The company’s strategy, using Roger Martin’s strategy framework, is built on three strategic choices:

Winning Aspiration: be the first choice for affluent urban millennials seeking sustainable snacks.

Where-to-Play: focus on affluent urban millennials who prioritize sustainability and organic products.

How-to-Win: differentiation by driving product innovation and maintaining a premium brand grounded in transparency and ethical sourcing.

To execute this strategy, the company commits to:

- Investing in R&D to develop innovative organic snack options.

- Building strong relationships with sustainable suppliers to ensure a consistent supply of premium ingredients.

- Allocating marketing spend to educate consumers about their brand values and sustainability practices.

Expectation for 2024 at the time of budgeting:

- Revenue $2 billion

- EBIT $240 million

Budget for 2025:

- Revenue $2.2 billion (10% increase)

- EBIT $276 million (15% increase)

1. Previous Year Didn’t Finish as Expected

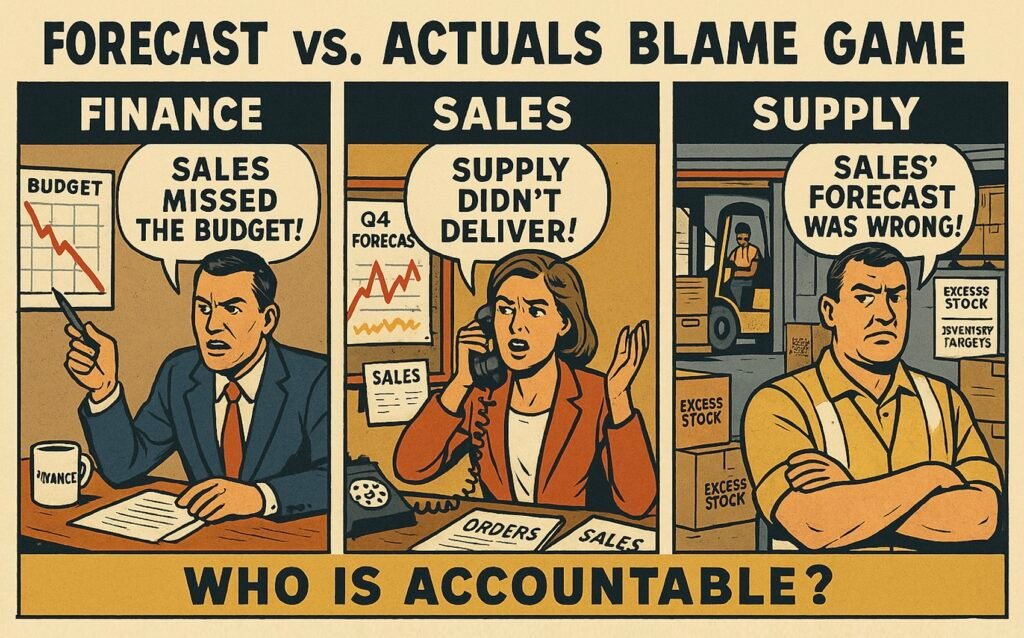

Due to lower-than-expected demand, competitive reactions, and increased raw material and logistics costs, the company finished 2024 significantly below expectations.

Actuals for 2024:

- Revenue: $1.9 billion (-$100 million from expectation)

- EBIT: $196 million (-$44 million from expectation)

Changes in assumptions:

- Raw material costs increased by 10%.

- Logistics expenses rose by 8% due to higher fuel costs and shipping delays requiring more expedited freight services.

- The premium organic snacks market grew five percentage points slower than expected.

- Competitors engaged in aggressive promotions, with price reductions of up to 15%.

As a result, to hit the budget in 2025, the targets were increased significantly:

- Revenue: Increase adjusted from $200 million (10%) to $300 million (16%).

- EBIT: Increase adjusted from $36 million (15%) to $80 million (41%).

However, the resources to achieve the targets remained unchanged.

In other words, assuming the original budget was both realistic and challenging, reaching the same static numbers would now be unrealistic—without luck or cheating.

2. ‘Stupid’ Actions to Reach Previous Year Targets

In an alternative scenario, given similar changes in assumptions, the company could have still ‘hit the numbers’, but only by taking actions that came at the expense of long-term growth (and were therefore not assumed in the budget).

For example, say the company reached its EBIT target of $240 million. To close the $44 million EBIT gap, it had to implement the following cost-cutting measures:

- Marketing Cuts ($10M): Eliminated digital campaigns, influencer partnerships, and in-store promotions, reducing brand visibility.

- R&D Cuts ($15M): Delayed product launches and canceled cost-saving packaging initiatives.

- Layoffs ($10M): Implemented a hiring freeze and cut jobs from development projects.

Additionally, the company artificially manipulated demand timing by offering discounts to customers willing to overstock their warehouses in Q4.

While beneficial in the short term, these actions had significant negative long-term impacts that the 2024 budget didn’t account for:

- Weakened brand & sales: Reduced marketing and sales presence eroded brand equity and retail relationships.

- Weakened innovation & cost efficiency: Delaying product launches and canceled packaging initiatives hurt the company’s ability to attract premium customers. Cutting R&D investments prevented the development of more efficient raw material sourcing and manufacturing processes.

- Lost future savings: Canceled development projects eliminated future cost-saving opportunities through improved productivity.

- Weakened Q1 2025 sales & profitability: The artificial Q4 sales boost created a revenue gap in early 2025.

In other words, although the company technically met its 2024 targets, the starting point for 2025 is significantly worse than budgeted.

All of this means that, as in the previous case, assuming the original budget was both realistic and challenging, reaching the same static numbers would now be unrealistic—without luck or cheating.

3. No Solid Business Logic Behind the Budget

To make matters worse, the 10% revenue increase and the 15% EBIT increase in the budget were not based on any business realities in the first place.

They were the outcome of political negotiations, where business units had initially presented more modest plans. However, after several revision rounds, headquarters imposed final stretch targets simply because they “sounded ambitious” and because “companies need to grow.”

In reality, the combined revenue growth from business unit plans was 7%, with an EBIT increase of 11%.

But to enforce stretch targets and build a buffer for unexpected events, corporate management imposed an additional three percentage points in revenue growth and four percentage points in EBIT, which were then assigned to business units by central finance—allocated purely based on business unit size.

No one had any idea where the additional growth would come from.

While having such stretch targets with no clear link to reality can push organizations to ‘try harder,’ they also have two major flaws:

- How difficult the stretch is depends on luck.

- They incentivize diluting the strategy.

For more on the latter, see the next section, “The Budget Logic Isn’t Aligned with the Strategy,” and for the former, see the following section, “Business Logic Becomes Inevitably Invalid.”

In short, as a result, stretch targets have zero likelihood of optimizing performance in the long term, as the odds that they are both realistic and challenging over the course of the year are next to nothing.

Even in the rare case that they are, the odds that they are also aligned with the strategy are practically zero.

4. The Budget Logic Isn’t Aligned with the Strategy

A simple reason for this is that many companies don’t even attempt to align their budgets with their strategies.

However, even when they do, the reality of strategic choices may not align with the reality of short-term financial expectations. As a result, the business logic behind the budget is based on how to reach specific short-term financial results, instead of how to successfully implement the strategy.

For instance, the assumption that the premium sustainable snack market will grow only 3 to 4% in the short term contrasts with the need for faster market growth to reach a 10% revenue increase (the exact numbers are obviously not the point).

To close the revenue gap, the company may ‘budget’ to engage in private brand deals that increase revenue but at significantly lower margins.

While such deals may support hitting certain numbers, they contradict the strategic premium positioning by shifting focus toward lower-cost, commoditized offerings.

Similarly, while the strategy would require investing in innovative organic snack options, building strong relationships with sustainable suppliers, and educating consumers about brand values and sustainability practices, all those actions increase short-term costs.

In order to get the budget numbers to match expectations, the company cuts R&D and marketing investments and chooses to work with suppliers with less sustainable practices but who offer lower-cost raw materials.

In other words, the budget becomes the company’s strategy, instead of being a tool to implement the strategy. See changes to the strategic choices below:

Where-to-Play:

- Before: Focus on affluent urban millennials who prioritize sustainability and organic products.

- After: Expand to cost-conscious consumers willing to compromise on sustainability. Increase presence in mainstream and discount retailers.

How-to-Win:

- Before: Differentiation by driving product innovation and maintaining a premium brand grounded in transparency and ethical sourcing.

- After: Introduce private label products and lower-cost options while maintaining a premium line. Reduce reliance on expensive sustainable ingredients.

Winning Aspiration:

- Before: be the first choice for affluent urban millennials seeking sustainable snacks.

- After: Shift from a niche premium brand to a leader in both premium and value organic snack segments.

Whether such a change in strategy is beneficial is unlikely.

It may be, but since the driver of these changes hasn’t been a real-life problem the company is solving—rather, it has been compliance with arbitrary ‘feel-good’ numbers—the odds that the revised choices will create unique value and competitive advantage are similar to playing the lottery.

5. Business Logic Becomes Inevitably Invalid

Regardless of whether the annual budget was based on strategy or not, the business logic behind the budget numbers inevitably becomes invalid, as the year goes on.

Take market growth assumptions, for example.

Whether the budget was based on revenue increases in premium sustainable products, legacy product segments, or the addition of private brands, the actual impact of those on revenue is never predictable.

Say the premium market growth assumption was 3% to 4%. What if the market is flat—or grows 8% or 9%? Or take the assumption that adding private brands would generate $50 million. What if it’s only $20 million? Or as high as $100 million?

The same uncertainty applies across the board. What if the assumed $100 million from new product launches turns out to be only $50 million because the company cuts half the launches to save costs (company’s decisions are different)?

Or what if it launches all the products, but consumers prefer competitors’ offerings (assumptions about consumers preferences or competitor actions turn out to be wrong)?

“It’s all about the execution,” right?

Maybe so, but what’s the point of executing to hit some arbitrary numbers? How is that a benchmark of what ‘good execution’ is? Why not excel in execution and deliver excellent results aligned with the strategy?

And as conditions constantly change, the results of ‘excellent execution’ differ depending on the context. The irony is that evaluating the ‘excellence’ of execution based on whether some static numbers are hit often leads to poor execution.

Read that again.

If you are still thinking that “real winners just deliver results and don’t blame conditions,” you’re neglecting the fact that this is a great principle only when the targets aren’t ‘stupid’ and when it’s impossible to lie or cheat to hit them.

Unfortunately, with annual budgeting, not only is lying and cheating possible, but both are actively encouraged. By enforcing the annual budget, you’re actually enforcing lying and cheating—not maximizing performance.

If you think real winners deliver results no matter what, then why not deliver 20% or 30% growth, instead of 10% (or whatever the budget was)? Too difficult? Not possible in the real world?

Was that an excuse?

Conversely, how are you a high performer if you hit your static 10% target while your competitors deliver 15%?

An astute reader will notice that the budget’s business logic may already be invalid based on how the previous year ended. If the company canceled product launches and development projects, then revenue projections and cost-saving assumptions have already changed.

And that’s just from the company’s own actions. On top of that, similar changes will come from competitors, markets, regulators, and other external factors, none of which can be fully predicted.

The fact is, if you’re chasing a static target, you’re likely chasing something that doesn’t reflect great performance, because real-world conditions will almost always differ from what you (implicitly or explicitly) assumed.

Similarly, there’s no logical reason to stick to resource allocations made a year in advance.

You don’t know ahead of time which business unit or project will need more or fewer resources. Maybe you need 1,000 people. Maybe you need 1,500. Maybe only 500. Who knows? You need to test the business logic behind the allocations and update it based on reality.

The testing period isn’t one year either. For some initiatives, it’s three months; for others, six or nine months. One size does not fit all.

“But that’s what we do anyway.”

Fine, then why do you need a static annual budget?

It becomes obsolete the moment you make one change.

Why keep tracking progress against it? You have new resource allocations and new assumptions. You need to test that logic and track execution against that—not against what it was two, three, or some arbitrary number of months ago.

6. Monthly Breakdown Differs from ‘Great Performance’

Even in the rare case that the overall budget for the year would still be valid, for virtual certainty, the monthly breakdown doesn’t reflect what ‘great performance’ would look like each month, nor does it represent an optimal allocation of the resources.

Great business performance isn’t a predictable line because the real-world context where businesses operate is probabilistic, not deterministic.

Further, the more detailed predictions you make, the higher the odds that ‘hitting them’ won’t align with great performance.

For example, targets of $80 million, $100 million, and $120 million for January, February, and March are less likely to represent great performance than a target of $300 million for Q1—and that is less likely to represent great performance than a target of $1 billion for the full year.

“But great performance requires constant progress.”

Sure, but that’s a different thing. You’re making a flawed assumption that hitting deterministic monthly targets is the best indicator of constant progress (or great performance).

It isn’t.

The odds are it’s hindering your growth.

If you hit monthly targets that are determined far in advance, it’s either due to luck or because you’re making questionable decisions to bend reality to match those.

By doing that, you’re probably generating unnecessary costs, missing real growth opportunities, and at the very least, wasting time and resources.

What should you do instead?

Focus on what you should do now based on changes in the business logic behind the numbers.

For example, if the logic behind the monthly targets was that the market will grow 5% and the company will acquire 10 new customers, how much did the market actually grow and how many customers were actually acquired?

What, if any, impacts do these changes in the business logic have for the future, and what decisions should be made as a consequence?

“That’s what we’re already doing.”

Maybe.

But if your decisions are driven how to close gaps to the arbitrary monthly targets, you’re chasing numbers disconnected from reality, instead of making the best possible decisions that drive growth.

The difference is that the actions will be different. You can manipulate short-term results with discounts, promotions, inventory tactics, etc., to ‘hit the plan,’ but that doesn’t improve real performance.

While the short-term tactics might seem to work (it’s possible to pee in your pants and feel warmer for a while), they come at the expense of long-term growth.

However, when you use the short term as an opportunity to learn more about the world, improve the logic behind your plans, and make the best decisions based on that, you can maximize the odds of long-term performance increases—even if it means missing some of the arbitrary short-term targets.

7. Shareholders Care More About Real Performance

One of the common flaws in how planning is done in publicly listed companies is the focus on ‘hitting the plan’ that has been communicated externally. This is based on the assumption that it’s what shareholders value.

While missing the plan can indeed have negative short-term consequences, maximizing long-term performance almost always requires it—and maximizing long-term performance ultimately leads to higher total shareholder value.

According to a study by Bain & Co. of almost 4,000 companies ranging from $50 million to $10 billion over 10 years, improving actual performance has 35 times more impact on total shareholder return than focusing on predictable earnings.

It’s ironic.

When you focus on ‘hitting the plan,’ you’re actually decreasing performance—and the reason for doing it is backwards: shareholders don’t ultimately care if you hit the plan or not.

Missing the plan is essential for maximizing long-term performance because static targets set a long time ago inevitably become disconnected from reality as underlying assumptions change.

This means static targets will likely become either unrealistically difficult or too easy to reach. Both cases hurt long-term performance. Unrealistically difficult targets lead to short-term sub-optimization (‘cheating’) at the expense of long-term, while overly easy targets lead to reduced effort and missed opportunities.

What to do instead:

Communicate the long-term vision and the business logic behind how to achieve it. This won’t prevent short-term fluctuations in the share price (or in financial results), but it will create more realistic expectations and attract investors who are in it for the long haul.

As Jeff Bezos has said: “In the short term, the stock market is a voting machine. In the long term, it’s a weighing machine. And we try to build a company that wants to be weighed and not voted upon.”

Instead of focusing on hitting an arbitrary estimate that will inevitably become disconnected from reality, focus on turning your long-term aspiration into reality.

This approach will bring bumps along the road, but that’s what great performance always looks like. It’s never a precisely predictable line of hitting static annual targets. Ironically, predictable earnings performance often signals poor performance: you’re leaving money on the table.

In other words, you need to make a choice: whether to hit the earnings predictions or whether to maximize long-term performance.

8. Small Improvements — Big Difference

Even when executives are aware of points #1 to #7, they are likely to say, “Well, it’s still close enough.” Meaning that while they understand the negative impacts of static budgets, they’ve had success with them in the past, and are likely to see the benefits of more dynamic approaches as marginal.

“But +10% is objectively a great increase. +12% isn’t dramatically different.”

Really?

For a $1 billion company, the difference is $500 million over 10 years.

Conversely, if 8% is more realistic while you’re pushing for 10%, that’s over $400 million in unrealistic growth you’re pursuing in the same period.

That’s another problem: when focused on annual results, you neglect the impacts of compound growth.

Ask yourself: What is the real-world business logic that makes +10% great performance, while +8% is too modest and +12% is unrealistic?

If you’re fixated on exact numbers, you’re missing the point.

The point is that when companies focus on ‘optimizing’ precise numbers, even though the difference in one year may be only a few percentage points at best, that ‘optimization’ is going to cost tens of percentage points of growth in the long term.

That is not only highly significant, but possibly existential.

It comes from a combination of doing fewer ‘stupid’ things that cost the company money and being open to more opportunities and experimentation, even if they have short-term negative outcomes.

9. ‘Stability’ Doesn’t Benefit Customers or Employees

One of the most common, but also one of the worst arguments for annual budgeting: ‘it brings stability.’

Oh yeah? Well, so does tying the rudder of a boat to the deck.

The ability to steer the boat is lost—but what the hell, as long as it brings stability, right?

While it’s indeed correct that annual budgets bring stability, it’s a mistake to state that as a ‘free benefit.’ As if it doesn’t have downsides, or as if those would been well understood and carefully weighted against the benefits of ‘stability.’

In reality, the benefits from ‘stability’ in steering a business are minor and benefit only one stakeholder group.

It isn’t the customer. Static resource allocations and the pursuit of static targets leads to worse products and confusion about who the customer even is. While obsessing over ‘hitting the plan,’ the company tries to serve everything to everyone instead of focusing on delivering value to a specific customer segment.

It isn’t the shareholder, either. As established earlier, shareholders care more about actual performance than about companies hitting their guidance.

Sure, the temporary dips in the stock are real and may have consequences, but over the long term, the argument that “we are a public company, and need to hit the guidance” is a myth. It may be a valid argument to cover your ass, but it’s not valid for maximizing total shareholder return.

It also isn’t (most of) the employees. Stability incentivizes lying and cheating because the real world is dynamic and probabilistic. Since people aren’t stupid, they understand this and resort to lying to build buffers for the inherent uncertainty to maximize their odds of ‘hitting the plan.’

In addition, since ‘the stable’ targets don’t measure real performance, people will cheat at the expense of real performance to hit them—not because they are inherently evil or incompetent, but because the system forces them.

Stability benefits only the bureaucrats who use it to steer the business, because it makes their job easy. A random person from the street can enforce compliance with static targets. It requires no understanding of the business and very little leadership or planning skills.

That’s not to say that the bureaucrats don’t know their businesses or lack skills, but the ‘easy’ mode may be a rational choice for them. The risk of failure is practically zero, there is no need to invest time or effort in learning something new, and it’s always possible to blame others for the ‘poor execution’ of the brilliant plan.

In addition, despite its flaws—or actually because of them—the advantage of annual static (‘stable’) targets and resource allocations is that they maximize opportunities to game the system. In other words, they increase the odds that people who run the system will hit their bonuses, regardless of the real performance of the company.

All alternatives focus more on actual performance, so the incentive to try them is not necessarily there for all.

So, while the stability that comes with annual budgeting may indeed be an advantage, it is that for only a very few—not for customers, shareholders, or most employees.

And it comes with a high price: poor company performance.

Conclusion

Most companies have an annual budget, and most are still holding on to it in the beginning of the year, despite being better off letting go.

They are neglecting the fact that, odds are, they didn’t finish the previous year as assumed in the budget. As a result, their targets for the current year are either unrealistically high or unambitiously low.

Additionally, the resources allocated in the budget are now either inadequate or excessive for reaching those targets.

Other companies that did reach their targets are ignoring the impact of all the ‘stupid’ things they did—things that were also not assumed in the budget.

For example, cutting costs last year may have undermined their ability to generate revenue or achieve cost savings this year.

The small number of companies that avoided these issues are likely in denial about the fact that their original budget didn’t have a solid business logic behind the numbers in the first place.

Unless they get incredibly lucky, their only option to ‘hit the budget’ this year is to do (more) ‘stupid’ things—harming the company’s long-term performance.

And the few companies that weren’t affected by that are likely fooling themselves into thinking their budget is aligned with their strategy.

In reality, even if they have a strategy, they haven’t aligned their budget with it—because they’ve prioritized hitting arbitrary short-term financial targets like “+10%.”

The only way to do that is by squeezing the business in the short term.

The long-term impact on company performance is the same as for those who are resorting to ‘stupid’ actions just to hit budget numbers without a solid business logic in the first place.

Companies that have avoided all these pitfalls so far are likely in denial that, by now, the business logic in their budget—even if it was aligned with strategy—has already become obsolete as some of the core assumptions have changed.

By sticking to the budget, the budget becomes the strategy, while the actual strategy becomes nothing more than words on a page, collecting dust in some drawer without any real impact on the business.

And even if—by some miracle—that hasn’t happened yet, one thing is 100% certain: the monthly breakdown of the budget does not reflect great performance.

By obsessing over monthly variances to the budget, a company’s ‘performance management’ is slowly but surely steering it toward doing, yet again, ‘stupid’ things—just to comply with arbitrary monthly budget numbers that have nothing to do with real performance.

Executives who recognize all these issues may still argue, “We are a publicly listed company, so we need to hit the guidance.”

Their mistake is believing that the stock market actually cares whether the company hits its guidance. Sure, in the short term it does—but in the long term, it cares 35 times more about real performance.

So, the argument that “publicly listed companies must do dumb things” is just another way of saying, “We are in the business of sub-optimizing the short term at the expense of the long term.”

Others will argue that the budget brings ‘stability.’

Well, great. It does. But who benefits from that stability? Not shareholders. Not customers. Not employees. The only ones who benefit are the bureaucrats who don’t know how to run an ‘unstable’ business.

So, if making executives’ jobs easier is the main priority, then stability is great. But if maximizing the company’s long-term performance is the goal, it isn’t.

Finally, even when executives understand all this, they are likely to dismiss the potential benefits as ‘marginal.’ And yes, sticking to an annual static budget may cost ‘only a few percentage points’ of performance in a given year.

Is that a lot?

Maybe not.

And maybe it’s better for most executives’ career progression.

But again, if the goal is to maximize the company’s performance in the long term, letting go of static budgets could lead to performance gains of tens of percentage points—on all significant financial measures.

Practical insights

- Account for the impact of how the previous year finished.

- Account for the impact of the ‘stupid’ things done to finish the previous year.

- Account for the possibility that the budget may not be based on solid logic.

- Account for the possibility that the budget may not be aligned with the strategy.

- The business logic in the budget is already obsolete by February.

- The monthly budget breakdown doesn’t reflect ‘great performance.’

- Shareholders care far more about real performance than ‘hitting the plan.’

- Small improvements in the short-term lead to significant long-term gains.

- The ‘stability’ of the budget doesn’t benefit customers or employees.