Read an annual report, listen to a conference presentation, or have a five-minute conversation with the average executive, and the odds are that ‘agility’ (the verb, not necessarily the concept) will come up in one form or another.

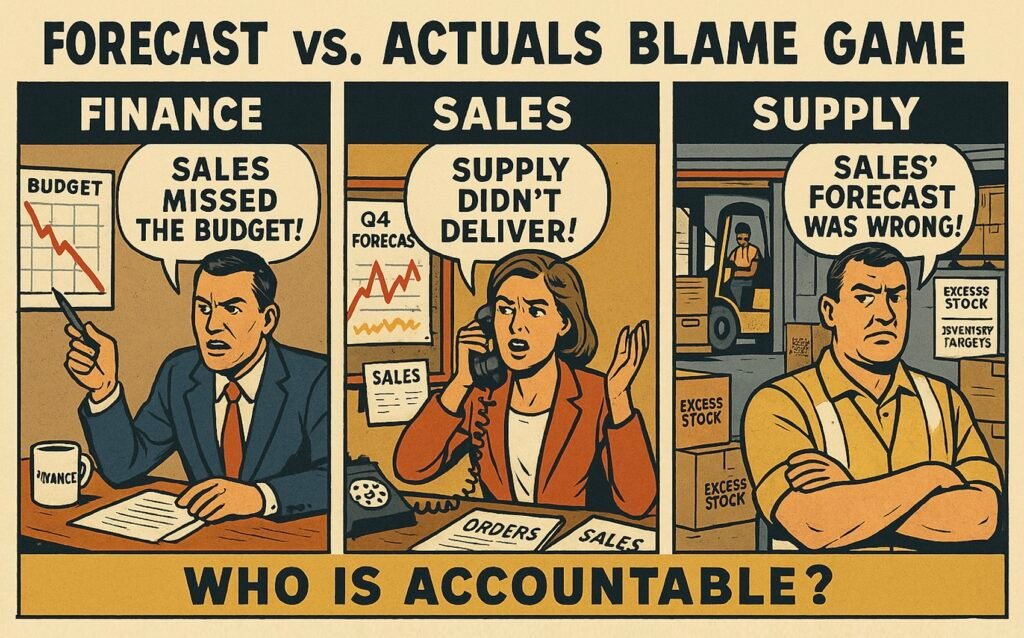

In most cases, the aspiration to be agile focuses on parts rather than the whole. This typically takes two forms: a siloed scope (narrow efforts within small parts of the company) and an emphasis on decision-making speed (rather than the broader impacts of those decisions).

Consider initiatives like rolling forecasting. On the surface, the logic seems sound: “Things are changing so fast; we need to understand their impacts and respond as quickly as possible.”

While that makes sense, the elephant in the room is this: even after implementing such systems, the most important targets—those tied to incentives—and the largest resource decisions are still made annually and remain largely set in stone.

The real message, then, is in fact this: “Do everything possible to hit arbitrary annual targets, even if they no longer make sense, using resources negotiated 9, 10, or however many months ago (and unless you spend all those resources, you’ll lose them next year, making it harder to meet next year’s arbitrary targets). But within those constraints, please, be as agile as possible!”

In other words, “As long as there are no major deviations in the most important factors impacting performance from what was decided a long time ago, be agile to respond to any changes in the environment since then.”

Additionally, much of the emphasis on ‘agility’ in business planning focuses on decision-making speed. Software vendors, in particular, capitalize on this:

“Why stick to a rigid monthly or quarterly planning cadence when modern software enables real-time decision-making?”

“In today’s VUCA world, you can’t wait a month to make a decision!”

“This software will reduce decision-making time from a month to a day!”

True, sometimes you cannot wait. But in practice, for most major decisions, it often isn’t the case—for a simple reason: agility is determined by the decision lifecycle—the time to make, execute, and commit to a decision. For major decisions, the first step typically pales in comparison to the sum of the latter two.

Take, for instance, the decision to launch a new product. Let’s say it takes a month to make the decision. However, product development—the execution of that decision—takes 6 to 12 months, followed by 3 to 4 years of revenue generation in the portfolio. In other words, the decision lifecycle is 4 to 5 years, or 48 to 60 months. One month accounts for just 2% of that.

Even if decision-making speed were revolutionized—from one month to one day (a staggering 2900% improvement)—on a system level, it would improve agility by only 2%.

To improve agility as dramatically as implied by the reduction in decision-making time, execution and commitment times would also need to be reduced by 30-fold. This would mean developing the product in just 6 to 12 days and generating equivalent revenue within 2 to 3 months.

Even if such reductions were possible—a highly generous assumption—they would likely increase product development costs 30-fold. Instead of launching a new product every 4 to 5 years, companies would need to launch one every 2 to 3 months.

For profitability not to suffer, one of two things would have to happen: either the new product would need to replace the demand of 30 others (thereby reducing complexity and solving a much bigger problem in the process), or customer demand would need to increase 30-fold.

In the first case, a single product would generate the same revenue 30 products (demand equivalent to 30 times the original demand) once did, achieving in 2 to 3 months what used to take 3 to 4 years—and there would be no need to add new resources to accommodate the faster product lifecycle. What an innovation!

In the second case, without cannibalizing demand for other products, overall demand would need to grow 30-fold. Otherwise, the revenues generated in 2 to 3 months wouldn’t match what previously took 3 to 4 years. While this could result in 30-fold higher development costs, admittedly that wouldn’t be a major issue due to the demand explosion. In any case, what an innovation that would be as well!

While these scenarios sound ‘amazing,’ the reason you don’t often hear them discussed is that, in most cases, they only highlight how delusional attempts to ‘improve agility’ by cutting decision-making time really are.

You’ll hear even less from software vendors about this because their tools don’t address the time needed to execute decisions—or the time required to commit to those decisions and reap their benefits.

Put differently, despite the sales pitches and amazing PowerPoints, the odds are their ‘revolutionary’ software doesn’t significantly impact agility in the real world—at least not at the company level and not when it comes to the biggest decisions (those with the greatest performance impacts) companies make.

In a nutshell, the irony of ‘wanting to be agile’ is that, while the underlying assumption is to improve company performance, it often involves changes that, even in theory—let alone in practice—have little impact on that. As a result, initiatives that sound good on the surface become more about perfecting the rain dance than actually changing the weather.

What should you do instead?

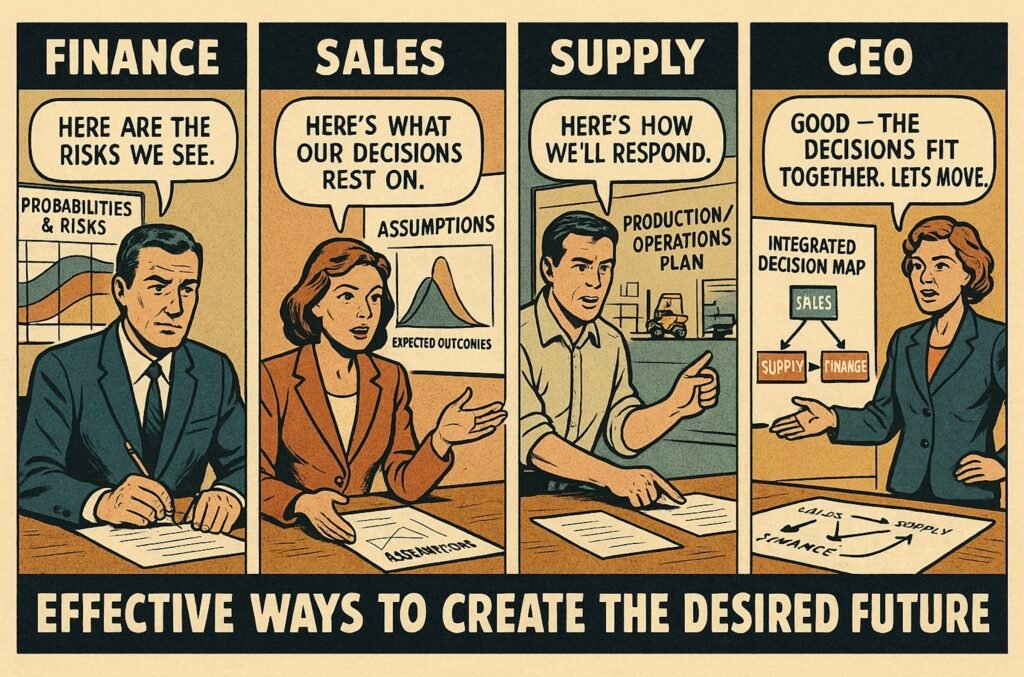

It’s simple: if you really aspire to be agile, adopt a holistic view and account for decision lifecycles.

If that seems too abstract, here’s a more concrete suggestion: get rid of annual budgeting. For those fixated on decision-making time, the biggest opportunity to reduce it for most companies lies in annual budgeting—where the time to make decisions is a staggering 12 months.

Talk about the opposite of agile!

Practical insights

- Decision lifecycles determine agility.

- Limitations to agility are set at the level of the system, not its parts.

- Annual budgeting is the biggest opportunity for agility for most companies.