Introduction

Successful executives often take pride in being highly focused on managing performance; they have a relentless drive for results. After all, anyone who isn’t, isn’t going to climb very high on the corporate ladder.

However, despite their success in driving results, they might still find themselves struggling with a lack of long-term growth. “How can that be?” they wonder. It must be due to poor execution from the organization, right?

After all, they have set clear targets and are rigorously enforcing efforts to close the gaps between those targets and actual performance. “They’re doing everything they can.”

Yes, a lack of effort or poor execution from the organization may indeed be one reason for the modest results. However, it’s neither the only nor necessarily the most likely reason. What executives often fail to recognize is that the very foundation their performance management is built on may be fundamentally flawed.

This is equivalent to choosing the wrong direction, misreading the signs along the way, and making poor course corrections—then wondering how, despite all the hard work, you never seem to reach the destination on time. And even if you do, it’s likely at the cost of reaching the next one.

Performance Management

Key components of performance management can be categorized as follows:

- Setting targets

- Incentivizing the achievement of those targets

- Monitoring progress

- Taking corrective actions

A typical example for many companies might look like this: Target setting happens annually, often in conjunction with the annual budgeting process.

For example, a company struggling with growth may set an annual target to reach revenue of $1 billion. To incentivize the organization to reach this target, annual bonuses and personal KPIs are aligned with it.

Once the targets are approved, the company establishes a regular review process, such as monthly meetings, where the actual performance of each business unit and function is monitored against the targets.

The primary focus of these reviews is to identify actions to close the gaps between actual and projected performance and the targeted (budgeted) performance.

So, what’s wrong with this?

It all seems perfectly logical, and many would testify to achieving excellent results using this approach. “It’s all about the execution,” right?

Well, yes. In general, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this approach, and it’s entirely possible to achieve good—even great—results with it. If that’s your experience, there’s no need to feel compelled to change anything.

However, if you’re still struggling to achieve the results you expect despite working this way, the underlying issue might lie in how you manage performance, rather than a lack of effort or “poor execution” from the organization.

There are two main reasons for this:

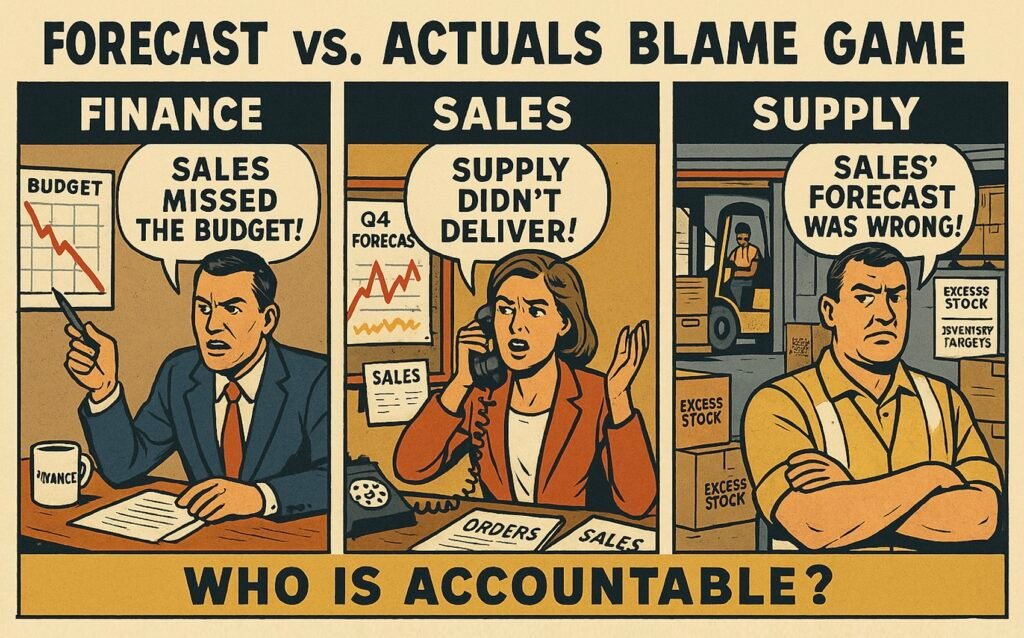

Put differently, performance management is often about managing a gap between ‘what performance shouldn’t have been’ and ‘what performance wasn’t.’

The Target Doesn’t Reflect Great Performance

The above description of performance management can lead to great results when the target truly reflects great performance. However, the way executives often set targets makes that unlikely.

Here’s how one financial expert with experience in Fortune 500 companies described the purpose of the budget:

“The annual budget (or operating plan) isn’t meant to be an accurate prediction six to twelve months out. That’s why we refresh forecasts every month. Instead, the budget is a commitment. And the analysis of actuals versus budget tells the story of how we track against that commitment we made at the beginning of the year.”

This is true: the budget is indeed a commitment. But that’s the problem. It’s often a commitment reached after an internal negotiation process—one disconnected from the customer, shareholder, and the real world.

A typical example for many companies is a financial point estimate at the end of the year—for instance, a revenue of $1 billion.

The fundamental assumption here is that great business performance can be described using precise point estimates at a specific moment in time. If this assumption holds true, focusing on closing gaps to such targets could be an effective approach to performance management.

Unfortunately, this is rarely the case in the real world. While it’s possible to get lucky or achieve seemingly good—or even great—results in the short term, the odds that static point estimates reflect great performance over the long term are low.

This is because, in addition to great performance, they also reflect the political negotiation power of stakeholders (e.g., hidden buffers or plugs). Furthermore, what constitutes real ‘great performance’ is always influenced by luck—making it often higher or lower than the original point estimate.

The ‘Actual’ Doesn’t Reflect Actual Performance

While many understand the issues with defining great performance, they often fail to recognize that what they use as actual performance also does not reflect true performance.

This may seem odd since actuals carry no uncertainty. A company can know down to the cent how much it sold last month. How could actual revenue not represent actual performance? That seems nonsensical.

There are two general reasons for this, beyond the obvious possibility of errors.

First, while the number itself may be factual, it can also include elements of manipulation. Consider weighing yourself on a scale: you’re trying to lose weight, and after a week, your weight has decreased by two pounds.

Does that mean your actual performance is a weight loss of two pounds? Maybe, but not necessarily. You can lower your weight through manipulation—by drinking less water, using the restroom, or spending time in a sauna before weighing yourself.

The actual number doesn’t solely reflect real (desired outcome) weight loss (loss of adipose tissue). It also includes gimmicks, such as emptying your bladder or manipulating water retention.

Similarly, in business, there are countless ways to manipulate short-term numbers: offering discounts, pushing products to customers prematurely, reducing inventories, expanding into non-premium products, targeting non-core customer segments etc.

Just like the scale, these numbers may create the illusion of ‘performance.’ But when evaluated against meaningful goals—such as improving health, increasing long-term sales, or creating shareholder value—they are not indicators of true performance; they are results of manipulation.

‘Playing the game’ can be exciting, and some may even view it as the essence of business. Most people understand this dynamic. However, there’s another often-overlooked factor: the influence of luck on outcomes.

Returning to the weight-loss example: it’s natural for weight to fluctuate in the short term, even with ‘great performance’ and no manipulation. Factors like glycogen levels in muscles, water retention, or the amount of food in the digestive system all contribute to variability.

In practice, this means your weight might increase by a pound, even if you’ve lost two pounds of adipose tissue over the week as expected. In other words, your actual performance is on track, but the measure you’re using tells a different story due to random fluctuations (luck) that can’t be controlled or necessarily even understood.

The practical consequence is that short-term, individual data points often hold little to no value in measuring actual performance, even if the metric itself is accurate.

That’s why someone trying to lose weight is often advised to use a two-week average of daily weigh-ins for a clearer picture of true weight loss. Daily measurements fluctuate, but comparing two-week averages provides a much better sense of progress.

Similarly, business actuals fluctuate due to random events unrelated to performance. Customers may adjust order timing, weather conditions might play a role, or a ship delivering goods could be delayed etc.

These are understandable and relatively traceable impacts. But there are also countless unknown variables generating random noise—such as variations and anomalies in customer behavior, competitors’ actions, technological discoveries, and their compound interdependencies.

Put simply, actuals never represent real performance—whether in weight loss or in business. Instead, they reflect a combination of real performance, manipulations, and the influence of luck.

Analogy – A Road Trip

Let’s explore the characteristics and potential real-world issues of traditional performance management using the analogy of a road trip.

Consider a family of four driving from New York to Montreal.

Road Trip Schedule

- Morning

- Departure Time: 7:30 AM (leave after breakfast).

- First Leg: Drive ~2.5 hours (~150 miles) to Albany, NY.

- Arrival in Albany: ~10:00 AM.

- Break: ~30 minutes (stretch, coffee/snack stop).

- Midday

- Second Leg: Drive ~2.5 hours (~160 miles) to Plattsburgh, NY.

- Arrival in Plattsburgh: ~1:00 PM.

- Lunch Break: ~1 hour.

- Grab lunch by Lake Champlain.

- Afternoon

- Final Leg: Drive ~1.5 hours (~80 miles) to Montreal, crossing the US-Canada border.

- Border Crossing: ~30 minutes (variable).

- Arrival in Montreal: ~4:00 PM.

In business terms, the commitment (i.e., the target or the budget) is to arrive in Montreal at 4:00 PM, which is analogous to achieving a revenue of $1 billion in 2025. The schedule outlines the plan (AOP) to achieve that.

Traditional performance management works as follows: The first performance review identifies a gap between the actual and the target. Instead of departing at 7:30 AM, the family leaves at 8:00 AM.

The analogy in business is a company finishing the previous year under target—for example, reaching $850 million in sales instead of $900 million. To reach the static target of $1 billion the next year, the required performance increases from +$100 million to +$150 million.

This shortfall could result from poor performance (taking too much time for breakfast for no good reason), poor planning (not setting an alarm), or bad luck (the mother had an urgent work call due to a crisis with a customer).

Sure, some reasons for the delay are fixable, while others are not. Regardless, the fact remains: the schedule is now compromised. Without changes, the commitment to arrive by 4:00 PM in Montreal can no longer be met.

Similarly, in business, the plan (AOP) was designed to grow profit from $900 million to $1 billion, not from $85o million to $1 billion.

If you ask a typical finance expert, they’ll tell you this is expected—and that’s where forecasting plays a role. Forecasting helps figure out how to fulfill the static budget commitment.

In principle, there’s nothing wrong with adapting. For example, the family might decide to cut the first break by 15 minutes and the lunch break to 45 minutes.

Great—forecasting to the rescue. The family is still ‘on track with the plan.’

But an astute reader might already notice a flaw in the analogy.

The family could make these adjustments only because the original plan was relaxed—not already challenging from the start.

The business equivalent would be an AOP with $50 million additional revenue can be added without additional resources. But how often are company budgets designed like that in the real world? It doesn’t really happen, does it?

Well, okay, CFOs often build hidden buffers and plugs into budgets. However, these are frequently hidden from the team, and such modifications are possible only if the original plan is ‘relaxed’—whether that’s transparent or not.

Let’s continue the analogy and see what happens when the plan isn’t relaxed or filled with hidden buffers.

Imagine the family reaches Albany on the (updated) schedule at 10:30 AM. According to performance management, that means actual performance matches great performance, right?

Maybe—but it ignores how that milestone was achieved.

If the original assumptions about speed limits were correct, then yes, great performance. But what if construction zones forced speed limits to drop by 20 mph?

Was it great performance if the family sped through construction zones, endangering workers, themselves, and risking fines or worse?

In business, the equivalent would be a company ‘hitting the quarter’ by pushing products into customer warehouses to counteract market downturns.

Conversely, what if the father forgot to fill the gas tank, causing an extra stop and losing 15 minutes—but low traffic canceled out the delay?

The business analogy would be a company hitting the budget despite losing a few customers, thanks to unexpected market growth.

Does traditional ‘performance management’ effectively learn from mistakes to ensure they don’t happen again? Okay, maybe there’s some potential for improvement, but we’re still on track with the plan. That’s what really counts, right?

Well, let’s see.

Say the next leg to Plattsburgh goes ‘as planned,’ but there’s a long delay at the restaurant. It takes over 30 minutes to get food, leaving the family only 15 minutes to eat and get back on the road. Doable? Sure. Now it’s time to ‘execute’: stuff the food at record pace, get the kids into the car, and go.

What’s some mild heartburn as long as you stay on track with the plan, right?

In business, the analogy could be a supplier having issues delivering raw materials, cutting down the product development time. To meet the original deadline, the company needs to work overtime and cut corners, potentially impacting quality.

But what’s the harm in some extra costs and decreased quality as long as you stay on track with the budget, right?

Now imagine it starts snowing. To stay on schedule, the family would need to drive dangerously fast in unsafe conditions.

The business equivalent: A market slowdown forces the company to cut corners, perhaps by switching to lower-quality materials that hurt product functionality or push the boundaries of environmental regulations.

But “real performers don’t complain about conditions—they deliver results,” right?

When the family reaches the border, there’s chaos.

The line at customs is far longer than expected. By the time they get through, it’s 3:30 PM. Even under normal conditions, it takes 45 minutes to reach Montreal, meaning the only way to meet the 4:00 PM commitment is to speed dangerously.

In business, this could be a sudden spike in raw material costs when the company has already exhausted all ‘reasonable’ (and even ‘semi-reasonable’) cost-cutting measures. The only option left to meet the budget is to cut costs so deeply that desired growth next year becomes unlikely or even impossible.

Should they do it?

What’s Really Happening

As the road trip analogy illustrates, traditional performance management isn’t about managing real performance. It’s about managing adherence to static arbitrary numbers set long ago, which might—or might not—have made sense under past real-world assumptions.

The issue is that it struggles to differentiate whether certain results stem from performance or luck. It also fails to question whether the ‘commitments’ still make sense to pursue under new circumstances or whether the targets are being achieved through improved performance—or through gimmicks that might ultimately hinder progress.

The practical consequence for companies is that they end up chasing meaningless—or even harmful—targets while engaging in counterproductive actions and failing to recognize opportunities to improve performance or seize potential.

Unlike companies, a family on a road trip might find it absurd to prioritize an arbitrary arrival time of 4:00 PM if conditions make it unsafe. “What does it matter whether we arrive at 4:00 PM, 4:30 PM, or 5:00 PM?”

It doesn’t—and none of these times indicate ‘worse performance.’ Ironically, they may even reflect ‘better performance,’ as targeting these times avoids unnecessary risks or costs that could harm longer-term outcomes.

The same logic often applies to business targets. In some cases, it’s essential to fix and meet them no matter what, but this is rarely true—especially when discussing a company’s overall financial performance. Or to be precise, it’s rare that meeting fixed financial targets truly aligns with great company performance.

Of course, there can be real consequences to missing such targets—but that’s a separate issue. It’s worth noting, however, that the idea “to maximize shareholder value, we must hit guidance” is a myth. In the long run, the stock market and shareholders care about real performance, not whether the company met arbitrary annual guidance.

In reality, hitting a $1 billion profit in one context may represent great performance, while in another, achieving $950 million might be equally—or even more—impressive. Similarly, over the long term (e.g., the next five years), how much revenue was created in 2025 will likely matter less than the growth achieved between 2024 and 2030.

Hidden Buffers

Demanding compliance with static commitments set a year in advance will inevitably lead to the creation of hidden buffers. In the road trip example, the buffers were transparent, but the plan was still ‘relaxed.’

In business, transparent and relaxed buffers are quickly eliminated. This, in turn, incentivizes the creation of hidden buffers and plugs, meaning the odds are that the original plans are not based on challenging yet realistic targets grounded in reality.

An ironic and unintended consequence of hidden buffers is that they enable worse performance when uncertainty turns out to be favorable. If the plan is buffered to account for bad luck, the odds are that it becomes ‘relaxed’ under most circumstances.

This is analogous to raising the water level to conceal hidden rocks. In business, this means the company loses valuable opportunities to continuously improve performance.

What You Should Do Instead?

For performance management to be effective, it has to manage real performance. This means it needs to focus on the gap between great performance and actual performance.

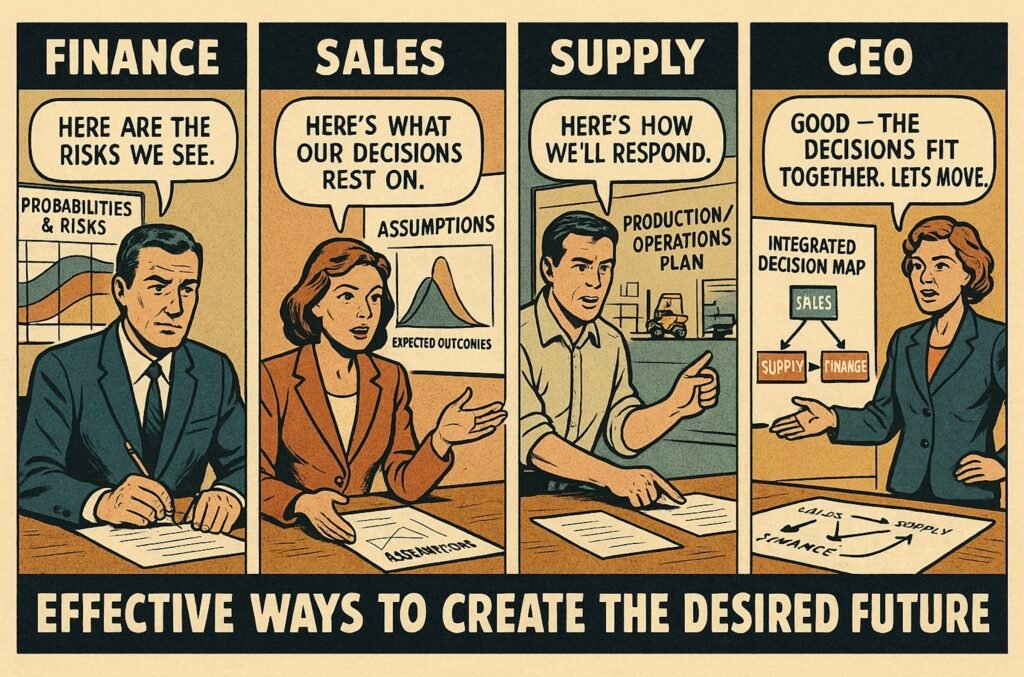

To do this, executives need to:

- Account for the impact of luck and artificial hidden plugs from targets.

- Account for the impact of gimmicks and luck from actuals.

First can be achieved by setting dynamic and relative targets and utilizing probabilities. The second can be achieved by focusing on multiple outcomes over time and changes in the real-world assumptions.

Account for the Impact of Luck and Artificial Hidden Plugs from Targets

In the road trip example, instead of setting a static target of being in Montreal at 4:00 PM, the target could be dynamic based on speed limits. This way, if there are higher speed limits, good performance to be in Montreal might be at 3:30 PM, or if the limits are lowered due to construction, it could be 4:30 PM.

An analogy in business could be that instead of a static $1 billion revenue target in all conditions, the target could be based, for example, on market share (not that it’s necessarily always a good measure).

For instance, reaching 24% market share, which in the current assumption of 5% market growth would lead to reaching $1 billion in sales, but in the case of a flat market, would lead to $950 million in sales, and in the case of 10% market growth, to $1.05 billion in sales.

The exact numbers, or metrics like the market share, are obviously beside the point.

However, this would still leave uncertainty about the delay at the restaurant, weather effects, and how long it would take to cross the border. While one could try to build dynamic elements from events that cannot be influenced, that will quickly get very complicated, difficult to quantify, and create unnecessary constraints.

For example, how to model dynamically the impact of the weather? What would be ‘great performance’ speed limits in different types of conditions: fog, light snow, heavy snow with icy roads, etc.? It is obviously not practical to even try to account for all variability in conditions in the targets.

In addition, some of the impacts you can remove or at least mitigate. For example, if there is considerable uncertainty about how long the breaks may take in a restaurant, pack a lunch. If the weather can have a significant impact, travel when the forecast is good. Those are all potential ways to improve performance, so it’s counterproductive to model targets in a way that would incentivize not being innovative.

So, while it may be advisable to incorporate some dynamic aspects (like the speed limit or market growth) into the target-setting, it is never possible, nor advisable, to build in all real-world elasticity into them.

This is where the use of probabilities can be useful.

For example, instead of setting a deterministic point estimate (even if it has dynamic components) of 4:00 PM (or which changes based on speed limits or the market), it is possible to account for all the uncertainty with probabilities by stating there is an 80% likelihood to be in Montreal before 4:00 PM (which implies that there is 20% likelihood that the arrival will be later than that).

In other words, the 4:00 PM in Montreal is a P80 target. It could also be a P50 or P90 target, or something else. A business analogy would be that there is an 80% likelihood that the 24% market share will be reached.

How likely a given target is to be achieved depends on the assumptions.

The probabilities are based on real-world assumptions, such as what is assumed about the traffic, weather, lines at the restaurant or the border, but they can also include the impact of random events such as accidents.

For example, there could be an 80% likelihood that the line at the border isn’t longer than the planned 30 minutes. Estimating the likelihoods can be made into a science, but an easy-to-understand baseline can be historical waiting times.

In business, there could be an 80% likelihood that the company is able to successfully launch the new products, and they result in the estimated (or higher) revenues.

When targets are dynamic and described with probabilities, it reduces the need to create hidden buffers to account for the uncertainty. In fact, if the focus is on improving the likelihoods, being explicit about the probabilities can incentivize to eliminate all hidden buffers.

The benefit of this is that the targets, and the following plans, are better based on reality, and everyone is better aligned with the real-world drivers behind them.

It’s obviously not possible to describe all possible sources of uncertainty or their impacts, but that’s irrelevant.

By using probabilities, it is always possible to improve the understanding of the world, just as a professional sports bettor can never know all sources that can impact the outcomes, nor be certain of the likelihoods of the factors she is able to identify. Yet she is still able to win millions by better understanding the odds of different outcomes.

Account for the Impact of Gimmicks and Luck from Actuals

Let’s say the family arrives in Montreal at 4:00 PM on the dot. Was that great performance?

Counterintuitively, based on a single outcome, it’s impossible to say. How was the line at the restaurant or the border? What was the weather like? How was the traffic? Were there unexpected events like accidents? Did they break the speed limits?

To answer the question, you need to ask, ‘under what circumstances?’

For things that can (and should) be modeled, the focus should be on the assumptions. For example, if the assumption behind the 4:00 PM target was that the border check would take 30 minutes, how long did it actually take?

All other things being equal, if there was no line and the border crossing only took 5 minutes, arriving at 4:00 PM isn’t particularly ‘great performance.’ In this case, the shorter time wasn’t due to the family’s actions, which means that ‘performance’ was worse than expected in some other area of the trip.

Evaluating how accurate the assumptions were is more beneficial than looking at end results alone. A better understanding of the assumptions can lead to deeper understanding of the world, improved predictions and to better decision-making.

It also helps weed out gimmicks that have little to do with actual performance. For example, speeding during the road trip, or in business, pushing non-core products to non-core markets merely to temporarily inflate revenues (while creating loss of focus, unnecessary complexity and costs).

Since the world is probabilistic, not deterministic, it is neither possible nor practical to describe all the potential factors that might impact performance. For instance, how could you model every possible weather or traffic condition and their combined effects?

To account for the influence of luck in outcomes, it’s better to focus on multiple results rather than a single instance.

In the road trip analogy, imagine the family makes the same trip regularly to visit grandparents in Montreal. While individual trips might be affected by random events, performance across multiple trips provides a better representation of actual performance and is less influenced by anomalies.

In business, whether a company hits an individual quarter or annual estimate, is less important than how well it performs over multiple quarters or years.

Performance management should focus less on whether an individual trip takes exactly 8.5 hours—which is meaningless in the big picture—and more on whether multiple trips fall within estimated probabilities.

What’s the difference?

The company reaches its objectives more often by focusing on real performance rather than random fluctuations, which are an inherent property of the real world.

Attempting to close gaps caused by random fluctuations decreases performance, while closing real performance gaps increases it.

Similarly, as with weighing yourself to track weight loss, executives should focus on conclusions drawn from multiple outcomes over time, rather than trying to force all individual outcomes to align with static targets.

Conclusion

How companies often practice ‘performance management’ leaves significant potential for improvement, as the influence of luck, gimmicks, and hidden buffers are not accounted for.

This means that performance management is often about the gap between ‘what the performance shouldn’t have been’ and ‘what it actually wasn’t.’ While it’s perfectly possible to improve performance this way, the odds are that some performance improvement potential is also missed.

To be able to better focus on the gap between ‘great performance’ and the actual ‘actual performance,’ companies should make their targets more dynamic and relative so that they remain valid (and worth pursuing) under various real-world scenarios, and utilize probabilities to account for the inherent uncertainty of the real world.

Similarly, when determining ‘actual performance,’ companies should focus more on longer-term trends than individual outcomes. Further, it is possible to find more valuable insights from the changes in the assumptions behind the outcomes than from the outcomes themselves.

The most common misunderstanding of the above is to think that ‘that cannot ever work, it gets too complicated.’ While some complexity may indeed be involved, there are two flawed assumptions behind such thinking:

- The ‘current’ way is effective, and its simplicity doesn’t reduce functionality.

- The ‘new’ way requires ‘modeling everything’ or making it complicated.

Neither is true.

These are typical made-up requirements people often like to use for all new things they encounter: unless this new thing doesn’t solve my problem perfectly and doesn’t have any issues, it’s no good.

They fail to recognize that to improve performance, all that is required is that the benefits of the changes outweigh the effort to make (including possible complexity) the changes.

And the odds are that’s possible for most companies.

Consider, for example, adding only one element—such as some dynamic components to targets, like accounting for speed limits or markets.

That’s already better than the alternative. Not perfect, not covering all possible issues, but better. And doing that is perfectly possible and not that complicated.

While ignoring these principles may not always prevent performance improvements, it often leads to missed opportunities and, at times, even incentivizes actions that decrease real performance.

The catch is that while these impacts are significant over the long term, in the short term, they can be negligible—or the current practices can even result in higher ‘perceived performance,’ making their elimination harder to justify.

Practical insights

- The root cause of poor performance may lie in ‘performance management.’

- Typical targets don’t always reflect great performance.

- Actual results don’t always reflect real performance.

- Account for the impact of luck and artificial hidden plugs from targets.

- Account for the impact of gimmicks and luck from actuals.