The Purpose of This Article Series

This will be a long series. While the title might suggest that this series is about definitions—or worse, yet another take on ‘the real’ way to define them—it isn’t.

In fact, it’s the exact opposite.

The main objective of this article series is to demonstrate the fundamental value drivers behind these terms that stem from first principles and hold true regardless of how the terms are defined.

A secondary objective is to show that excelling in strategy, planning, or execution is impossible without excelling in all three—and that the definitions, regardless of what they are, are subjective and can be, at best, irrelevant and, at worst, actively harmful.

Depending on the definition, everything can be categorized as ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ or ‘execution’—or any combination of the three.

Why invest time in reading this series?

Here are some typical symptoms of companies suffering from the problems addressed in this series:

- Lack of long-term growth.

- Poor profitability.

- Poor performance, regardless of how it is defined.

- Lack of agility.

- Struggling to ‘hit the plan.’

- Obsessing over ‘hitting the plan.’

- Cutting marketing costs (again) to ‘hit the plan.’

- Frustration with annual budgeting.

- Frustration over ‘why the numbers keep changing.’

- Wondering what’s ‘in’ the numbers.

- Arguing over which numbers are ‘right.’

- Misalignment between functions or business units.

- ‘No clear strategy.’

- Creating 100-page ‘strategic’ plans.

- Struggling with ‘strategy’ or ‘strategy execution.’

While this series is not a ‘how-to’ manual or a complete solution to any of the above, it will help those experiencing these issues understand why they occur and what can be done about them.

Introduction

In literature and social media, strategy and ‘execution’ are hot topics, even though there isn’t a commonly accepted definition for either.

There is an abundance of experts and best concepts for both, which is at least a bit ironic given that most companies apparently struggle with both.

Depending on the consultants or ‘thought leaders,’ either having a good strategy or excelling in execution is portrayed as the key to maximizing business benefits.

Planning, on the other hand, is often marginalized and downplayed by advocates of both groups. Strategy and execution are cool. Planning is uncool.

For strategists, planning is ‘technocratic,’ something that operates in certainty, dwells on details, and has no major impact on the customer, the company’s profitability, or anything that truly matters.

It’s a necessary evil, like paying taxes.

For ‘executionists’ (pun intended), planning is slow and rigid. It’s ‘endless.’ It kills agility. It’s about dreaming of the future without ever taking action. It’s about creating overly detailed plans that quickly become obsolete as the world changes.

It’s like an overprotective parent who takes all the fun out of being a kid.

In a way, both perspectives are partly right and partly wrong.

They are right that much of the critique highlights real issues in how ‘planning’ is done in many companies. However, they are also wrong, as much of the critique fails to understand what effective planning looks like.

It’s more critique of a caricatured version of planning: it critiques bad planning.

While that may sound dismissive, it’s no different from saying that defining strategy as the creation of 200-page PowerPoints filled with incoherent lists of things someone might do someday is ‘bad strategy’—which is exactly what ‘strategists’ do.

Or rejecting the definition of execution as spending days ‘firefighting’ urgent issues—jumping on the first solution that comes to mind and running with it, only to create more fires that will soon also need urgent attention—without planning.

Even though that’s more or less what ‘execution’ often looks like in companies.

But just as there is good and bad strategy, and good and bad execution, there is also good and bad planning.

This series will examine the differences between good and bad strategy, planning, and execution—showing that, despite varying definitions, certain fundamental characteristics determine whether they are ‘good’ or ‘bad.’

Even with the battle lines drawn between different groups, how one defines each term—or how brilliant any individual part is—becomes irrelevant; in the end, it’s the interplay of the whole that matters.

The Ultimate Problem

Every outcome—whether personal or business-related—stems from the sum of all decisions made, plus luck. This holds true whether an individual is trying to live a happy life, or a company is maximizing shareholder value over time.

Ultimately, success depends on the cumulative impact of all decisions—not on any single choice. And that impact is driven by every concept influencing those decisions, not any single approach—whether strategy, planning, execution, agile, OKRs etc.

No concept can maximize performance without accounting for every mechanism that steers decisions. Otherwise, it results in sub-optimization—where even the best method for some decisions is constrained by the weakest link in the system.

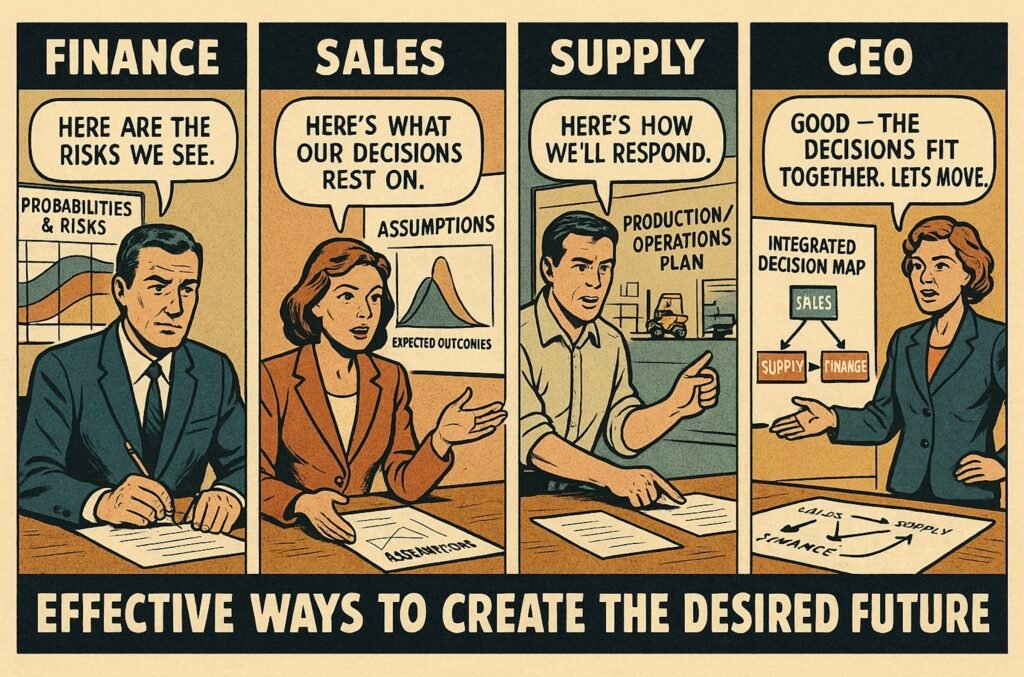

Picture 1.

Sure, some decisions have a greater impact than others, but ultimately, success depends on the cumulative total.

The strategic choice to compete in the premium segment is meaningless if tactical decisions—such as whether to launch Product A or B, how much to invest in branding, or when to time that investment—don’t add up to the desired overall outcome.

Worse, the processes driving these decisions can contradict each other:

- Strategic planning is done at executive off-sites, often with little to no accountability for the end result (regardless of what that is).

- Resource allocation happens through annual budgeting, often shaped by internal politics rather than strategy.

- Product launch decisions follow budget constraints, focused on short-term targets at the expense of long-term value.

The decision to launch a product doesn’t matter if execution is poor, if there are too many competing priorities, or if planning is unrealistic.

Even the most brilliant strategy fails if resource allocation decisions or supplier selection decisions are made poorly in ‘planning.’

Consider Target’s expansion into Canada.

The choice was to play in Canada and win with brand. But tactical decisions failed—opening 124 stores in poor locations at once instead of phasing rollout, cutting inventory system testing to meet the launch deadline, and choosing suppliers for speed over capacity.

The result? Billions lost and a full market exit.

Conversely, even world-class execution won’t salvage a flawed strategy, such as using cutting-edge technology in a low-cost market where customers care more about price than features.

The real challenge isn’t just ensuring some subset of decisions—like strategy or execution—works well. It’s about ensuring all decisions add up to the desired total outcome.

While some decisions may be the focus for a given timeframe (a quarter, a year), a company ultimately lives with the cumulative impact of all decisions over time.

For most companies, that number grows too high too quickly for any single mechanism to handle.

Individuals make 35,000 decisions daily, 95% of them subconscious, leaving roughly 1,000 conscious work decisions per person per day.

Applying the Pareto principle, let’s estimate that 100 of these drive 90% of results.

For a company with 1,000 employees, that results in the following total number of decisions over time (see Picture 2).

Picture 2.

This is the problem for strategy, planning, execution, or any other framework: they each attempt to improve how a part of these decisions are made.

But the ultimate problem is how all mechanisms shaping these decisions together maximize the odds of achieving the desired total outcome.

Why Is Understanding the Ultimate Problem Critical?

Understanding the ‘ultimate problem’ is critical because all business concepts are part of a solution—not the entire solution.

This means a concept’s value in helping a company achieve its goals isn’t determined solely by its direct benefits.

Two more fundamental factors define its usefulness for a given company (particular system):

- Does it address the bottleneck of that company (system)?

- How well does it fit with the other concepts used in the company (system)?

A company might benefit from ‘better strategy’—a consultant might highlight obvious flaws in the current ‘strategy’—but improving strategy alone won’t matter that much if resources and targets are still locked into a rigid annual budgeting process, and people’s resulting behaviors are to lie and cheat to suboptimize their own silos.

Similarly, while a rolling forecasting (planning) process would offer clear advantages over ‘rigid’ annual planning, implementing it wouldn’t necessarily improve anything if resources and targets were still set annually (rigidly), and bonuses—which determine behaviors—were focused on suboptimizing the short term.

Most people focus on one business concept at a time: strategy, rolling forecasting, driver-based planning, agile, OKRs, and so on.

And that’s fine. Eat the elephant one bite at a time, and so forth.

But unless they recognize that these individual concepts are only parts of the ultimate problem, they’re like someone ordering the latest home shopping network exercise gadget that promises rock-hard abs in just five minutes a day.

The model with rock hard abs and 10% body fat didn’t get that way by using the widget for five minutes a day. Her physique is the result of tens of thousands of disciplined decisions regarding eating and exercising.

Most business concepts are marketed with the same gimmicks:

- “Google is using these.”

- “This is how Jeff Bezos ran Amazon.”

- “Here’s a case study of a company that did this.”

But that’s like promoting fitness gadgets, supplements, or training programs that a specific professional athlete or team has used. The fact that they used them is neither proof of causality nor the only—let alone the biggest—factor contributing to their success.

Sure, the stories may be half true—but so what? What was the overall context? What were all the mechanisms steering their decisions? And even that is ignoring the influence of luck.

No matter what the widget is—if you’re consistently eating more calories than you burn, you’re never going to see your abs, no matter how well you ‘execute’ or how brilliant your ‘strategy’ is.

It also doesn’t matter what part of the decisions summed up to calorie intake being higher than calorie consumption, let alone what you called those parts—whether it was ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ or ‘execution’ that failed. The outcome doesn’t care.

The same holds true in business.

To evaluate any business concept, you must understand not just how it works in isolation but how well it integrates with all the other concepts that steer decisions in that company.

When you grasp that, you’ll also realize that there are no ‘best’ concepts—just as there is no single best exercise widget or training program.

But just because there’s no ‘best’ training program doesn’t mean some fitness principles don’t work better than others.

Which principles work better depends on the problem being solved, the objective, and the other principles in use.

The same applies to decision-making in business.

There are fundamental principles for steering decisions that are more effective than others, depending on a specific business problem, goal, and the other principles in use.

For example, ‘agile’ principles might be highly beneficial in how teams operate, but companies with command-and-control leadership practices and rigid annual budgeting processes might not get many real benefits out of them.

However, there is no single “best”—let alone only one—definition for such principles or broader terms like strategy, planning, or execution that use those principles.

All the terms are about ‘knowing the name of something,’ while the fundamental principles that drive value are about ‘knowing something.’

The Difference Between Knowing a Name of Something and Knowing Something

In the 1981 BBC Horizon documentary The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, Richard Feynman tells a story about how, as a boy, his father taught him an important lesson about the difference between knowing something and knowing the name of something.

His father used to take him on walks in the woods on weekends to teach him interesting things about nature.

One day, when Feynman was playing with other kids, one of them asked:

The kid: “Do you see that bird? What bird is that?”

Feynman: “I don’t have the slightest idea what bird that is.”

The kid: “That’s a brown-throated thrush. Your father doesn’t teach you anything.”

But Feynman thought it was the opposite.

His father had taught him that the bird was called a brown-throated thrush, but he would also add that in Portuguese, it’s ‘sabiá-de-garganta-marrom,’ in Italian, ‘tordo dalla gola marrone,’ in Chinese, ‘棕喉鸫 (zōng hóu dōng),’ and in Japanese, ‘茶色の喉のツグミ (chairo no nodo no tsugumi).’

Then he would say, “Now, you know in all these languages what the name of that bird is, but you still know absolutely nothing about the bird.”

Knowing what a bird is called means ‘knowing a name of something’: how different people in different places call the bird.

Knowing what kind of bird it is means ‘knowing something’: how the bird sings, what it eats, how it builds its nest, and so on.

A lot of what has been written about strategy, planning, or execution is about what different people call strategy, planning, or execution—in other words, they are about ‘knowing the name of something,’ not about the fundamental characteristics that create value—‘knowing something.’

In fact, it’s even worse.

While a bird is a real, physical creature, business concepts are not.

There is no fixed concept of ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ or ‘execution’ in the real world to which different people simply assign different names.

Instead, ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ and ‘execution’ are abstractions—ways to label different types of decisions, how they are made, and how they are steered.

Just as a brown-throated thrush is a specific species that belongs to a specific category of birds, which are types of animals, which in turn are types of living organisms.

However, biological categorizations are much more unambiguous (though debates exist) than business categorizations, which are almost like the ‘wild west,’ where anything goes.

The problem is not only that there are no universally accepted categorizations but also that, unlike biological categorizations, the criteria used are often not even descriptive of the real-world characteristics.

In fact, often the categorizations are purely nonsensical.

Some are similar to categorizing all birds as animals that have a heart and lungs. Well, most animals—of very different types—have a heart and lungs, so how’s that useful?

For example, some say that strategy is about decisions made under uncertainty and competition. Others say that strategy is about the what and why, while planning is about the how and when.

Still, others argue that strategy is about integrated choices that create focus and fit, whereas planning doesn’t require cohesion between choices.

Well, most business decisions are made under uncertainty and competition, and they are also often about the what, why, how, and when at the same time.

Moreover, all ways to group decisions—like strategies, plans, frameworks, roadmaps, and policies—are about integrated choices that create focus and fit.

Similarly, according to some, a core characteristic of ‘execution’ is to focus rather than trying to do too many things at once.

So, if strategy, planning, and execution are about focus and fit, how is that supposed to be helpful?

Or if it is up to anyone to define these terms, whose definition should we believe—the one who is most famous, has the most followers on social media, or the longest career in consulting?

No wonder there’s a never-ending supply of ‘this is the real way to do this’ best practices—the same as there is a never-ending supply of ‘revolutionary’ diet and exercise programs, and widgets that promise rock hard abs in only 5-minutes.

And this doesn’t even include the fact that the definitions often contradict each other.

For example, one expert says that strategy is a logic and a plan is a process, while another emphasizes that strategy is an ongoing process.

What does that mean—strategy is an ongoing plan?

Strategies are plans, after all?

(To be continued in Part 2: Terminology Debate)

Practical insights

- It’s not possible to excel only in strategy, planning or execution.

- A lot of the discussion around strategy, planning and execution is terminology.

- The ultimate problem is what all decisions sum up to.

- Knowing a name of something is different from knowing something.

- Effectiveness of business concept depend not only on the effectiveness of the individual concept, but where the bottleneck is and how that concept fits with all other mechanisms to steer decisions.