The Problem with All Business Concepts

The problem with all business concepts, including strategy, planning, and execution, is that they often emphasize solutions over problems.

It’s like having a hammer and seeing everything as a nail.

That’s why you end up with definitions like: “Strategy and execution are the same, and the sum of the two covers all decision-making.”

And although it’s certainly possible to describe all decision-making in a company as nested ‘strategies,’ matryoshka dolls within matryoshka dolls, and it may be a simple (simplistic) way to describe it, that doesn’t mean it is an effective way to make or steer decisions.

That’s because it’s not always a hammer that you need.

Sometimes you need a hammer, sometimes a saw, and other times a screwdriver.

It depends. It depends on the problem.

In many cases, the business problem itself is not well understood, such as identifying the root causes of lack of long-term growth.

Instead, consultants, along with the organizations they advise, become fixated on the latest revolutionary concept that promises transformational benefits, regardless of whether it actually addresses the company’s real challenges.

It’s like arguing the general benefits of the latest revolutionary diet or exercise program without really understanding whether the real problem is to be in the best possible shape for your wedding in six months, to win a bodybuilding competition next year, or to maintain a healthy weight and mobility for life, and why that’s hard.

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ celebrity diet or exercise program that effectively solves all of these problems for all individuals. The right solution depends on the problem and its context.

Similarly, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ business concept that addresses all business problems for all companies. Not even one that addresses a type of problem like ‘lack of growth.’

So, while a ‘lack of growth’ is indeed a real business problem, it’s a broad and vague one, much like ‘how to be in better shape’ is a broad problem for a bride, a bodybuilder, or an obese person with mobility issues.

Growth issues can stem from an infinite number of factors, and a ‘hammer’ is not always the ‘solution’ to all of them for all companies.

Understanding the Business Problem Is Only Half the Equation

Beyond failing to identify the business problem, consultants (or whoever is offering the hammer) often overlook that understanding it is only half the equation.

The other half is identifying flaws in the system of company’s decision-making mechanisms is what caused these business problems in the first place or what is preventing them from being solved.

Somewhere, someone has either made poor decisions or failed to make good ones that could have addressed the business problems.

What decision-making mechanisms led to that?

It’s the same as why any individual is in poor shape or unable to make decisions that would improve their fitness. Those reasons are always specific to the person.

Failing to diagnose what’s wrong with the decision-making mechanisms means that any proposed ‘solution’ may not have much effect, as decisions will be overridden or altered by existing legacy mechanisms.

Take ‘strategy,’ for example.

It may be easy to point out that a company’s 200-page PowerPoint presentation, labeled as its ‘strategy’, fails basic tests of what constitutes a ‘real strategy,’ such as creating focus and fit among choices.

Perhaps it’s just an incoherent list of pet projects assembled during a two-day offsite.

Here’s the thing.

Even if that PowerPoint isn’t a ‘real strategy,’ that doesn’t mean the company lacks one. And changing it to a ‘real strategy’ wouldn’t necessarily improve performance.

The Real Steering Mechanisms Aren’t Necessarily Well Understood

As strategy experts like Roger Martin have pointed out, strategy isn’t what a company says it will do; it’s what it actually does.

That applies to all decision-making: deciding to do something and actually doing it are two different things.

It also means that how a company claims to make decisions, or what it says steers its decisions, isn’t necessarily how decisions are actually made or steered.

While this may sound like another terminology debate, it involves a critical distinction: something, regardless of its label, is steering the company’s decisions.

And that something, or those ‘somethings’, aren’t necessarily explicit mechanisms like what’s officially called a ‘strategy’ or the latest XYZ 4.0 planning process.

It’s the same as language: people may not be able to explicitly state the grammar rules of their native language, but that doesn’t mean the rules don’t exist or that they can’t speak and write fluently.

The contents of a PowerPoint document aren’t a ‘real strategy,’ regardless of its formatting, if they don’t guide decisions. If no decisions stem from it, and if those decisions don’t influence others, then its impact on performance is meaningless.

This is often the case with 200-page ‘strategies.’ As many authors have pointed out, these documents typically gather dust in drawers and are rarely referenced.

They don’t fail because they violate arbitrary formatting rules, whether they fit on a single page or can be communicated in under two minutes, but because they don’t steer real-world decisions.

And influencing decisions is the only way strategy impacts company performance.

That said, just because a 200-page strategy document lacks clear choices that create focus and fit doesn’t mean the company itself hasn’t made such choices.

A company may already have a solid, well-enforced set of strategic choices, ones that, while undocumented, drive most decisions.

These principles might exist solely in the CEO’s or executive team’s heads, but if they reinforce them in every meeting, they steer all company decisions.

Alternatively, strategic choices may be deeply embedded in the company’s culture after decades of practice.

No one needs a PowerPoint slide to remind them that the company ‘plays’ in premium and ‘wins’ with brand; that’s simply part of its identity, and has been like that for over a century.

So, when a consultant comes in to create a ‘real strategy,’ they may succeed in replacing the 200-page deck with a neatly laminated one-pager.

But if that one-pager merely formalizes the ‘strategic’ decisions the company has followed for the past 100 years, it won’t change how decisions are made, and therefore won’t change company performance either.

And even if there is room to fix the strategy, doing so may do little to improve performance, unless strategy is the bottleneck to better decision-making.

Solutions Don’t Necessarily Address the Bottleneck

Even if a company lacks a clear set of strategic choices and a strategy exercise produces better ones, that doesn’t necessarily mean performance will improve.

That’s because the bottleneck steering decisions may not be the strategy or how strategic choices are made. It may be another decision-making mechanism, for example, the annual budgeting process.

No matter how brilliant the strategic choices or the mechanism for making them, they will have little impact if the annual budgeting process, where targets and resource allocations are set, ultimately overrides them.

For example, if a company has an arbitrary rule to increase profits by 10% every year, that may, in practice, be the real strategy, if we define strategy as the primary force driving all decisions within a system, unrestricted by any other factor.

While this also may at first seem like a terminology debate, it’s deeper than that.

It’s about understanding the fundamental characteristics of decision-making within a system, specifically, which decisions hold the greatest relative influence.

That’s a fundamental characteristic of certain types of decisions, not all decisions, regardless of what they’re called.

In most companies, the dominant forces that steer all decisions are annual targets and budgets, which, in many cases, are effectively the same thing.

So, while a company may have ‘strategic’ choices centered on premium positioning and brand strength, it will only adhere to them if it can still ‘hit the budget.’

If it can’t, it will seek ways to bridge the gap, perhaps by extending into lower-price segments, even if that contradicts its supposed strategy.

And while such ‘exceptions’ to the strategy may be marginal at first, over time, this dynamic can create a negative spiral that gains momentum and eventually dilutes the ‘strategic’ focus and the competitive advantage that comes with it, the very thing the strategy was supposed to create.

It’s like ‘comfort eating.’

Enjoying treats every once in a while won’t ruin your diet, but if you resort to comfort eating every time you feel bad, and not sticking to your diet makes you feel bad, you’ll eventually find yourself adding a lot of extra weight.

So the bottleneck for someone wanting to lose weight may not be a better exercise or diet program, let alone an exercise widget, but rather their tendency to comfort eat, which will undermine the benefits of any diet or exercise plan.

Similarly, if the real bottleneck is the budgeting process, then focusing on refining strategic choices, without addressing the fact that the budgeting process will override them when push comes to shove, as it inevitably will, will at best be ineffective.

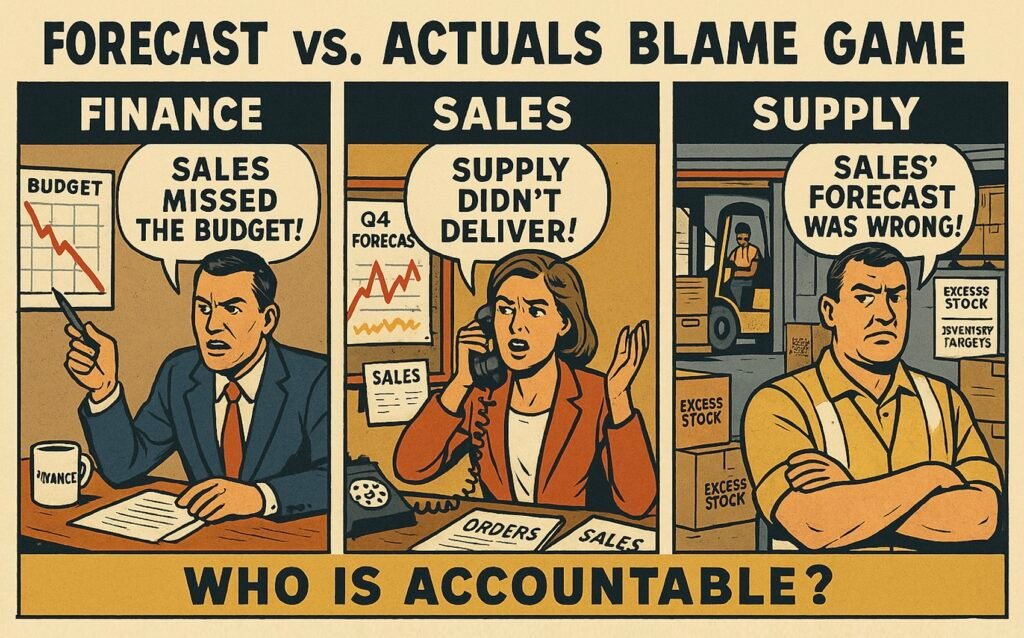

And the real bottleneck may not even be an explicit alternative decision-making mechanism like annual budgeting. It may be the bad behaviors that the mechanism causes, like cheating and lying.

As Richard Rumelt writes in The Crux, the real problem in business isn’t which financial model to use, it’s incompetence and lying, which can render any model ineffective or even counterproductive.

So, if a company has mechanisms that incentivize cheating and lying, like annual budgeting, the bottleneck to better decision-making isn’t the absence of ‘real’ strategy, the lack of a cross-functional planning process, or the latest AI system.

It’s the bad behaviors caused by the annual budgeting process and static targets that will eat any such ‘mechanical’ improvements for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

And the reason for having annual budgeting is not the official explanation, ‘to meet shareholders’ expectations’ or ‘to have meaningful targets to implement the strategy.’

It’s the executives’ risk aversion and command and control leadership style.

So, while there may indeed be multiple logical issues in the mechanics of the company’s decision-making systems, such as rigidity and the absence of clear choices that create focus and fit, the bottleneck is the executives’ leadership style and skills.

And without addressing the bottleneck, it too will eat any mechanical change, like ‘real strategy’ or ‘rolling forecasting,’ for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Businesses Already Have a Working Steering Mechanism

A common symptom of business concepts being focused on solutions rather than problems is that those proposing new ways to make and steer decisions often overlook the fact that all functioning businesses already have a working mechanism for decision-making.

‘Working’ meaning a holistic system that produces value for someone, regardless of whether it could do so much more effectively.

It could be debated whether this applies to failing businesses as well, so for the sake of simplicity, we’ll restrict the definition to companies that are making money.

All profitable companies generate value for someone.

No company is aimlessly doing everything.

All have made some choices; all have some degree of focus.

Most are not operating in every country in the world; that’s a choice.

No company serves all customers in the world; that’s another choice.

No company operates in every part of the value chain, and so on.

Could many businesses improve the focus of their choices? Absolutely.

Could that help them perform better? Probably.

Are there gaps and contradictions in the interaction of their different decision-steering mechanisms? Most likely.

Could they improve the fit of all their decision-making mechanisms? Probably.

But regardless, they already have a working set of mechanisms for how decisions are made and steered.

What those mechanisms are, or how ‘good’ they are, is secondary.

Any new mechanism must be implemented with consideration of how it fits into the existing system, not just how effective it is on its own or in some other context.

It’s like how, while the properties of a set of tires or an engine matter, what’s even more important is how well they fit a specific car.

A working car is a working system, and while there may be tires with better grip and engines with more horsepower, whether they improve the functionality of a specific car depends on its other parts.

Legacy Mechanisms Influence What Is the Best New Practice

People who claim to have the ‘right’ or ‘best’ way of doing something often overlook that its effectiveness is context-dependent. They act as if their customers are blank slates, free of legacy mechanisms that steer decision-making in their companies.

However, in established companies that have customers and are making money, that is never the case.

This means legacy mechanisms influence:

- How effective the new ‘best practice’ can be.

- The effort required to realize its benefits.

Both depend not only on the new ‘solution’ itself but also on the company’s existing decision-making mechanisms.

For example, if the bottleneck to growth is that the company is trying to be ‘everything’ for ‘everybody,’ a ‘real strategy,’ a continuous process that generates an integrated set of choices positioning the company to create a competitive advantage, may indeed be an effective solution.

However, if the leadership style is command-and-control and, as a result, the processes for setting targets and allocating resources are not only rigid but also based on political negotiations—where compromises are made to avoid disappointing anyone—a continuous process for revising and finding the best ‘strategic choices’ is unlikely to fit well with the company’s other mechanisms, making it less effective.

At the very least, the effort required to realize the benefits will be much greater, and the probability of success much lower.

On the other hand, implementing a continuous strategy process in a company with continuous planning processes will require much less work and has a much higher probability of success than implementing it in a company with rigid planning practices—not only because of the mechanical differences but also because of differences in existing mindset and behaviors.

Probability of Achieving the Benefits Is Not 100%

Having the ‘right solution’ often comes with the side effect of exaggerating its potential benefits. You’ll rarely hear a realistic assessment of the expected value of a particular solution’s benefits.

They may highlight absolute benefits, like adding 5% to margins or 10% to revenue (often also exaggerated), but they rarely acknowledge that the probability of achieving those gains is far from 100%.

There are no certain or even near-certain ways to add tens of percentage points to any business’s performance, regardless of the business problems they face or their legacy decision-making systems.

The difficulty, and the high likelihood of failure, comes from the fact companies attempting major transformations are fundamentally changing how they operate and behave. By definition, that carries significant risk.

So when evaluating a new decision-making mechanism, the expected benefits are: potential value added × probability of success.

For example, let’s say a ‘real strategy’ adds 10% to revenue. That sounds great. But if the probability of success is only 10% to 20%, the expected revenue increase is actually just 1% to 2%, not 10%.

And that doesn’t come without additional effort.

So the real business case for change isn’t “This will add 10% to your topline.”

That assumes 100% probability of success.

It’s “This will take X amount of time and money to add 1% to 2% to your topline.”

The added benefit will still be 10%, but only 1 or 2 tries out of ten will succeed.

That’s why 1% or 2% indicates the relative attractiveness of one option compared to another. For example, the company would be better off pursuing an initiative that adds 3% to revenue but has over a 90% probability of success—assuming similar time and effort required.

Whether that change is worth making depends on what other opportunities the company has to increase revenue, how else it could invest that time and money, and what the expected return would be.

Simple to Explain ≠ Effective

Most business concepts, and people selling them, are biased toward being ‘easy to sell’ rather than ‘effective in solving real problems.’

It’s the same reason why gadgets promising extraordinary results with little to no effort or diets that let you eat whatever you want for four hours after fasting for 20 are far more popular than their actual effectiveness would justify.

They are easy to understand, seem like simple solutions to complex and difficult problems, and are therefore easy to sell.

Take, for example, a common ‘simplification’ of the difference between strategy and planning:

- Strategy is about what you control.

- Planning is about what you don’t control.

Sounds simple, right?

No, in fact, it sounds simplistic.

The difference between simple and simplistic is that simplistic, while appearing simple, reduce functionality.

They make decision-making (or steering) mechanisms easier to explain (to sell) but less useful for making or steering decisions.

Terminologies are subjective, so there is no arguing whether one definition is ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ but that doesn’t mean all definitions are equally useful in making or steering decisions.

Defining strategy as what you control and planning what you don’t control is not particularly useful for two reasons:

- All decisions involve both what you control and what you don’t control.

- It conflicts with more established strategy definitions that are grounded in first principles.

Think, for example, of the decisions in Roger Martin’s video ‘Strategy is not a plan.’

One can control the decision and its output for both ‘strategic’ and ‘planning’ decisions, but not all the outcomes (business impacts), see table 1.

Table 1.

While you could argue that it’s possible to control outcomes, like costs, of some business decisions, you can also argue, as Roger Martin does, that lower costs are always a way to create customer value, gain a competitive advantage, or increase profits.

All his examples of ‘strategic decisions’ have an outcome of lowering costs, but that, in turn, leads to attracting cost-conscious customers and enabling competition with ground transport, which is, as Roger Martin argues, the real business value.

Similarly, while you can argue that you ‘control’ the outputs of building a plant, launching a product, or hiring new people—you can make the same argument as for the strategic decisions Martin listed, that you control their costs—you can also argue that no one makes those decisions solely to save costs.

There is always an uncontrollable element, like increased revenue or, at the very least, a value add to the customer or the company, which in turn increases its power to capture a bigger share of the profits (which it doesn’t control).

So, at best, you are lost in long subjective debate about ‘what are decision outcomes’ and which of them you control. Or, in other words, even if the high-level distinction is ‘simple,’ in reality, it’s simplistic: it doesn’t truly clarify much, it can even create more confusion, and it doesn’t help in making or steering decisions.

And even if you were able to make such definitions, you’ve also managed to divide the whole into parts. That conflicts with many established definitions of strategy, which argue that strategy is about the whole, not any of the parts.

Take, for example, Porter (from Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy):

“Another common mistake is confusing marketing with strategy. It’s natural for strategy to arise from a focus on customers and their needs. So in many companies, strategy is built around the value proposition, which is the demand side of the equation. But a robust strategy requires a tailored value chain—it’s about the supply side as well, the unique configuration of activities that delivers value. Strategy links choices on the demand side with the unique choices about the value chain (the supply side). You can’t have competitive advantage without both.”

So, while you ‘don’t control’ the customer side but ‘can control’ the supply side, Porter’s definition is that strategy is about the whole: “it’s inherently integrative, it’s how the various pieces function together.”

Whether that is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ is subjective opinion, but in terms of functionality it is also grounded in first principles. There is a distinct use for a concept (and a label for that) that encompasses the whole.

What decisions steer an entire system of decisions? That clearly applies not to all decisions but to some decisions and such a functionality would be useful in a way to steer decisions.

Someone else might disagree and say that strategy is about what you don’t control, but how is that useful in making or steering decisions?

Especially when it supposedly steers only part of the decisions, not the whole, so it not only destroys the value in Porter’s definition, but leaves it open what is then the mechanism that steers the whole?

Simplistic definitions also fail to explain why mechanisms that steer a business should be easy or simple. When is that ever the case for anything of value—let alone something as complex as a business?

Porter has written thousands of pages about strategy and needed an entire new book as an ‘executive summary’ of his views on strategy.

Think about the arrogance of people summarizing it into dichotomies like ‘what you control’ or ‘what you don’t control.’

Even operating the simplest home appliances requires thick manuals.

So why should an effective way to steer a business fit on a single page or be reduced to a trivial dichotomy like ‘what you control’ and ‘what you don’t control’?

In fact, believing that’s a reasonable requirement is often the root cause of why businesses struggle to improve their decision-making mechanisms—not because they lack the right framework, but because they try to implement mechanisms whose complexity doesn’t match the complexity of their environment.

Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety

Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety states that you can’t steer a complex system with simple rules. Or, put another way: “Only variety can destroy variety.”

Any time someone claims that a simple thing will produce transformational benefits, you should take that claim as seriously as you would claims that an exercise widget or training program will single-handedly get you into great shape.

Sure, in the right context—alongside many other good decisions made consistently over time—you might get into great shape. But it won’t be because of any ‘simple’ widget or program.

In any system, the number of responses available to the decision-maker must at least match the complexity of the challenges the system faces.

If the external environment presents more variations than the system can handle, it will struggle to adapt and stay in control. To avoid this, the decision-making approach needs to be just as sophisticated as the problems it’s trying to solve.

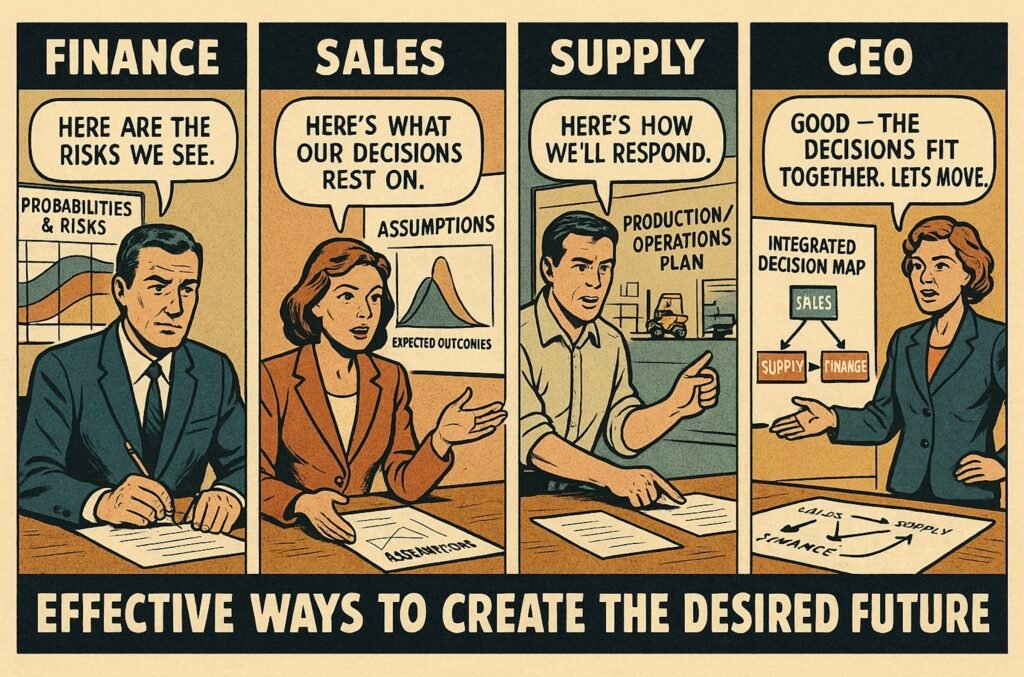

In business, this means companies need a range of decision-making mechanisms.

If a company’s decision-making mechanisms lack variety, they won’t be able to keep up with the complexity of their environment.

That means all decision-making mechanisms that appear simple and promise transformational results are, in fact, simplistic and misleading.

This is one of the fundamental reasons why companies struggle to gain benefits from agile, OKRs, or any specific business framework like ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ or ‘execution.’

Only by building variety that matches the complexity of the environment—whether through ‘strategy,’ ‘planning,’ or ‘execution,’ or whatever the decision-making mechanisms are called—can businesses effectively influence their futures.

Simplistic decision-making mechanisms make good social media posts—or even good books—but they are never effective solutions for how an entire company operates.

(To be continued in Part 4: The Problem)

(Read also Part 1: Introduction and Part 2: The Terminology Debate)

Practical insights

- Don’t propose a solution if you don’t understand the problem.

- The real steering mechanisms of a business are not always well understood.

- The effectiveness of business concepts depends on the legacy systems.

- Probability of achieving benefits is never 100%.

- It’s impossible to steer a complex system effectively with simple rules.