Introduction

“You absolutely cannot make a series of good decisions without first confronting the brutal facts.” – Jim Collins

Most executives recognize many of the flaws of annual budgeting, but they also have many irrational reasons for continuing to use it. While continuing to run an annual budget may ultimately be the right conclusion for them, many are unable to make a rational decision or even engage in a rational discussion about it.

To do that, they would have to confront the brutal facts—and to do that, they would need to let go of many of their flawed rationalizations for why running an annual budget is a good idea.

This article will debunk the nine most commonly used flawed rationalizations for annual budgeting. None of them mean that annual budgeting is useless in all cases or for all organizations, but understanding them enables executives to engage in rational discussion about whether annual budgeting is the best option for them.

1. To Set Targets

Many executives use budgets as synonyms for targets.

Common alternative expressions of the same:

“Budgets are commitments.”

“Budgets are performance contracts.”

“Budget is the destination.”

They argue that annual budgets are needed because otherwise the company wouldn’t have sensible targets—or it would somehow wander aimlessly. The underlying belief is that budgets are a great way to maximize company performance.

The reality is that they are a great way to steer the entire company into doing all kinds of dumb things to achieve arbitrary numbers, but a poor way to maximize performance.

The simple reason is that point estimates set 12 months earlier for a calendar year never align with what good performance would be.

That’s because the world is unpredictable, and there is nothing anyone can do to predict what number would reflect great performance after 12 months.

Even in the theoretical case that this were possible, the very fact that budgeting is used almost synonymously with target setting ensures—well, that and human nature—that there is a zero probability the process will produce great targets.

The reason is simple.

Since people are going to be measured against what they can negotiate in the process—not what would actually be high performance—the process is guaranteed to produce biased, political compromises that are all over the place.

All over the place—except where great performance would be, given all the facts. Even in theory.

In other words, annual budgeting is great at producing targets that often make little to no sense to achieve.

That’s why, despite its popularity, rationalizing annual budgeting with excellence in target setting is undeniably one of the worst reasons to run one.

2. High Performance Standards

This is related to the ‘target’ reasoning but expands on it. The typical logic goes something like this: instead of ‘constant replanning,’ the company focuses on ‘execution’ because it has ‘high performance standards.’

Especially many old-school CFOs take pride in this.

Their thinking is that sticking to static, agreed numbers reflects a no-nonsense, high-performance culture focused on results instead of excuses for why it can’t be done.

However, not only do they ignore the earlier point that budget targets are often nonsensical to hit in the first place—they also fail to understand that having static, absolute point-estimate targets means they have dynamic performance standards based on dumb luck.

That happens for the same simple reason it’s impossible to set sensible point-estimate targets 12 months in advance: the world is probabilistic.

There’s no escaping that.

Either targets account for it, or it will automatically be baked into the level of difficulty to achieve them.

In other words, no matter how high the standards may have been set in the budgeting process, by dumb luck, those same numbers can be average or easy to achieve by the end of the year.

Or they can be totally impossible to achieve—and the whole company knows it.

As a result, instead of even trying to achieve them, they tank the current year’s performance (since it’s already lost) in an effort to maximize their chances of getting more reasonable targets for next year.

In other words, ironically, the ‘high performance standards’ are not only not high—they’re often the reason performance is low.

To make matters worse, since annual budgeting has an arbitrary calendar-year scope, it by definition dismisses all business impacts of decisions that fall outside of that.

That, in turn, opens up a Grand Canyon–sized gap to cheat—to ‘hit the budget’ by improving calendar-year performance at the expense of following years.

So, by the very nature of annual budgeting, it never reflects high performance standards—because it doesn’t even include the performance impacts of the biggest decisions.

That’s an undeniable objective fact, not an opinion. Unlike the rationale that annual budgeting is a way to set ‘high performance standards.’ That’s 100% opinion, not based on facts or logic.

Whether or not annual budgeting is the right thing for your company is one thing, but having high performance standards is not a valid reason for it.

3. Accountability

Keeping people accountable is a classic—closely related to the previous reasons.

This one, however, does have some truth to it. Annual budgeting, and the resulting static point estimates, is indeed a great way to keep people accountable.

Its main benefit is that it makes it easy.

A fifth grader could hold people accountable to the annual budget.

It literally takes no skill or knowledge.

All you need to do is compare two numbers. Is 8 higher or lower than 9?

Well, if 9 is the budget and 8 is the actual or projection: “Your performance is not acceptable and what the hell are you going to do to close that gap?”

See? It’s easy.

You don’t even need to know which company it is, whether the numbers make any sense, whether it’s possible to close the gap, or whether it even makes sense to try.

You can just yell, bang your fists to the table and fire people unless they improve.

So, if the argument is that it’s the world’s easiest way to keep people accountable, then yes—that’s a 100% valid reason.

However, add a tiny bit of realism, and it falls apart: does it make sense to hold people accountable to budget numbers?

Yes, this is a close cousin of the ‘target’ and ‘high-performance standards’ arguments. And the answers are still the same.

Since static budgets are nonsensical, not aligned with what good performance looks like, and allow for cheating (by not accounting for the performance impact of major decisions), they are an awful tool for accountability.

That is, if the intent is to hold people accountable for great performance.

If the intent is to hold them accountable for hitting numbers that don’t make sense to hit in the first place—by any means necessary, including cheating at the expense of company performance—then yes, annual budgeting is a great tool.

However, not many proponents of annual budgeting would publicly confess that this is why they value the accountability aspect of it—which means their accountability arguments are, in fact, nonsensical.

4. Strategy Implementation

This is most often heard from finance professionals or consultants. The argument goes something like this: the budget operationalizes the strategy.

And sure, there is some truth to that.

It does involve translating strategic choices into next-level decisions—like making resource allocation decisions. That’s what budgets are: resource commitments.

And those are made at a level that most would agree aren’t ‘strategic.’

So, what’s the problem?

The problem is with the characteristics of annual budgeting—not with budgets or resource allocation decisions per se.

Since annual budgets, by definition, are set in stone 12 months in advance for a calendar year, they create an alternative, competing, and often conflicting steering mechanism to the strategy.

Strategy is about focus—about which customers the company serves and how.

It’s about how the company wins and succeeds over time, not limited to a calendar year or quarter.

Incentivizing people to hit specific numbers at specific time intervals creates pressure to serve a broader set of customer needs in a variety of other ways.

And the number of decisions available to ‘hit the budget’ is always far greater than the decisions that align with specific strategic choices.

Why can’t you just set constraints on the customers and the ways to hit the budget?

Well, in theory, you could.

But that’s where the conflict lies.

Which ultimately steers the business?

The strategic choice to focus on premium products for customers who value high quality—or hitting the EBIT target of $100 million by the end of the year?

“Both.”

Then you’re facing the ‘target’ problem again. It’s impossible to set a fixed 12-month target that remains relevant within specific strategic constraints.

And even if it were possible, since the cutoff for annual budgets is the calendar year, you’re still left with the ‘cheating’ problem.

To grow the premium business, you’d need to invest in R&D and marketing this year—while most of the benefits wouldn’t arrive until subsequent years.

Even if you stayed within the strategic constraints this year, you could still artificially inflate this year’s numbers at the expense of the future—or more specifically, at the expense of the strategy.

All of this doesn’t even account for the basic fact that there’s no such thing as a static strategy. As virtually all strategy experts agree, strategy involves evolving set of hypotheses you need to test.

By its nature, annual budgeting leaves no room for testing hypotheses or learning. It assumes the right answers are already known and that it’s just up to ‘execution’ to hit the numbers.

In other words, it’s one of the worst tools you could use to implement a strategy, as the budget always ends up eating the ‘strategy’ for breakfast—when the whole point of having a strategy is that the strategic choices are what steer all other decisions.

When they don’t (like when the annual budget is the most important thing), the company no longer has its intended strategy.

It results in the tail wagging the dog.

Therefore, as far as strategy implementation tools go, annual budgeting is one of the worst, as it often ends up destroying the strategy.

5. Financial Decisions and Resource Allocation

Sure, that’s what happens in annual budgeting. And yes, it is indeed one way to do those. But how effective is it?

Turns out, not very effective at all.

The reason is simple: how many financial decisions are best made once a year?

Or which resource allocations are most effective when made only once a year?

Even companies that run annual budgeting don’t stick to their financial decisions or resource allocations throughout the year.

Ask any marketing director whether their marketing budget has ever been adjusted (i.e., reallocated) during the year, and watch them burst into laughter and ask, “Are you serious?”

Ask any cost center owner whether their cost budgets have ever changed during the year because the ‘revenue budgets’ (a misnomer, really) didn’t pan out.

Ask any CFO to list all the major financial decisions they make during the year—and how many of those were made during the annual budgeting process.

Ask any CEO whether most of their acquisition decisions are made during budgeting—or when opportunities present themselves.

Ask any business executive whether they make major business decisions during the year that weren’t in the budget. All of those decisions also involve major financial implications.

The reason no company—anywhere, ever—has stuck to its financial decisions and resource allocations from annual budgeting is simple: all companies live in a reality where they make major decisions continuously.

The only major decisions annual budgeting is good for are the annual resource allocations.

But the problem is that since all major business decisions are made continuously, financial decisions and resource allocations tied to an annual budget are, by definition, always disconnected from reality.

That means that while it’s possible to use annual budgeting as a tool to make financial decisions and allocate resources, it’s inferior to more dynamic methods that better align with the cadence and impact of real business decisions.

So the idea that you need annual budgeting because you have to make financial decisions and allocate resources is not a good reason.

No company really needs annual budgeting to do either, and there are no real business decisions that make annual budgeting an effective tool.

6. Alignment

If anything, it’s the opposite.

This is nonsensical already for the simple reason that the goals it aligns people around are themselves nonsensical.

However, even as a tool for creating alignment, annual budgets are deeply flawed.

For several reasons.

First, because of its characteristics, there is no mechanism to test and adjust the hypotheses. That means the ‘alignment’ is 100% theoretical and 0% tested in practice. It’s paper alignment, not real alignment in actions and behaviors.

Second, also due to its characteristics, annual budgeting is more of a political negotiation than a transparent planning process that seeks the truth.

As a result, whatever alignment is achieved is often based on distortions—if not outright lies—and highly biased, incomplete versions of reality.

This is amplified by the first point: there’s more freedom to lie, cheat, and manipulate, because (again, by design) there’s no mechanism to test those stories in practice.

“But, we monitor performance rigorously against the budget.”

Well, you may do that, but by the time you do it, the budget is set in stone.

Whatever bullshit story you were able to sell at the time of budgeting—even one that misaligns with everyone else—that’s what the monitoring is against.

So, ironically, monitoring against budgeting can lead to monitoring that the original misalignment stands—no matter how flawed it was. Further, even if the original budget were aligned, as reality starts to deviate, there is an incentive to lie again.

Management won’t want to hear that you’re ‘off budget,’ so you won’t tell them. In reality, you are—and executing something completely different—but no one knows. So, they are executing something that is no longer aligned with what you are doing.

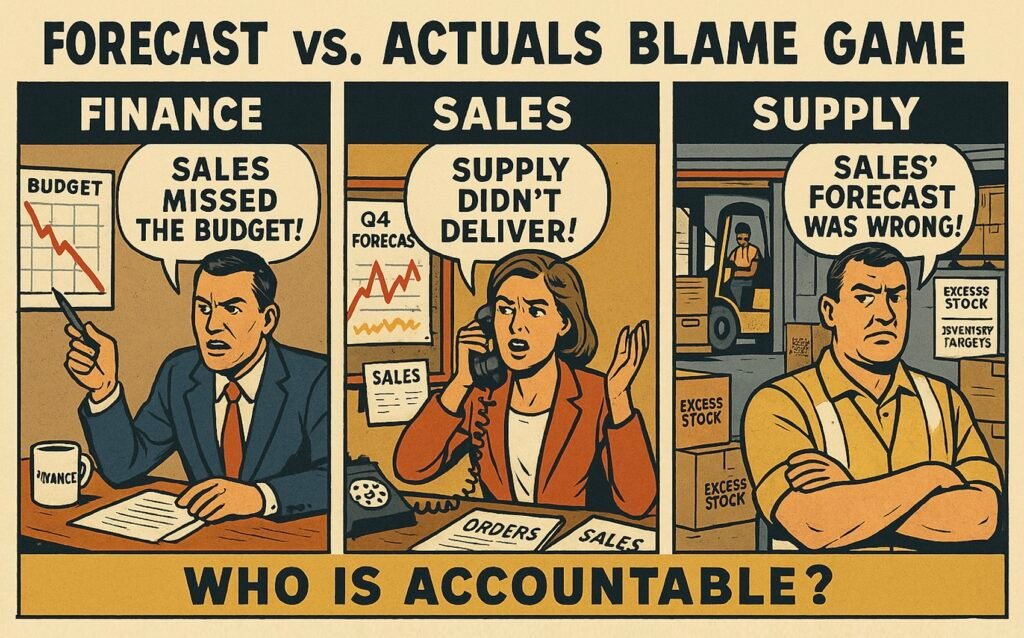

Strict budget enforcement is more likely to lead to functional misalignment over time, until everybody is forced to face the brutal facts—which is typically when it’s too late to do anything about it.

In other words, third, while an annual budget may create alignment around numerical outcomes, it rarely creates alignment in actions.

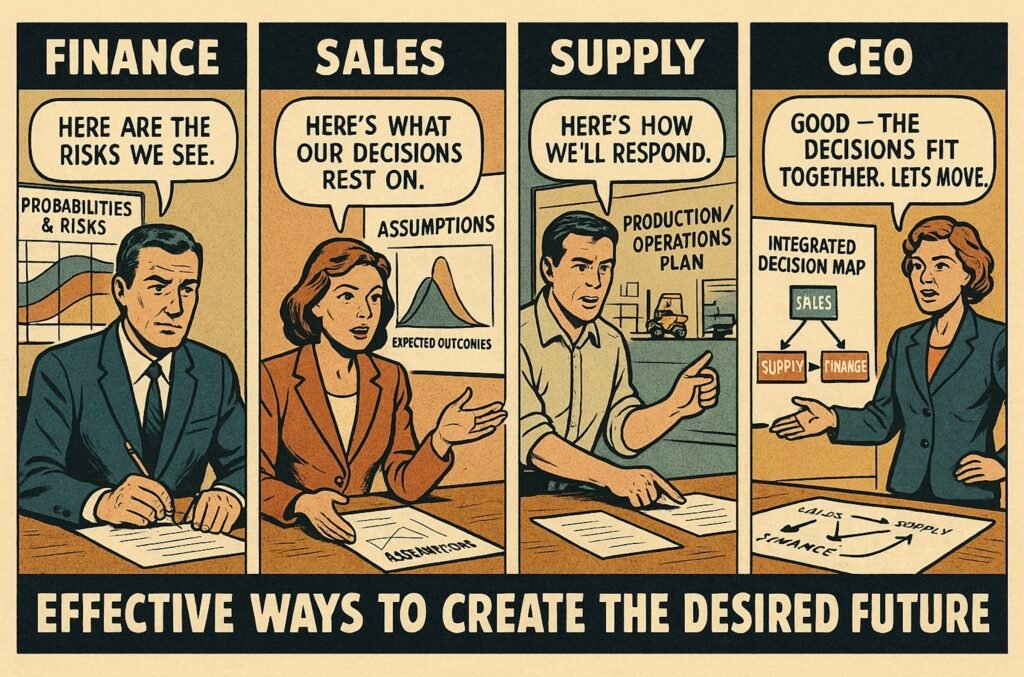

For example, even if everyone agrees that sales should be 100, the product team may be focused on products that serve different customer needs than what sales is targeting, and the supply chain might be producing something entirely different that maximizes their odds of hitting their own numbers.

In the end, everyone blames someone else for why the numbers didn’t add up.

Further, because annual budgeting is driven more by political negotiation than by a grounded understanding of what’s really happening or what should be done, there are often ‘management adjustments’ that have no basis in reality.

Total revenue across all business units is too low?

No problem.

Corporate simply adds another $100 million, which the FP&A department divides in Excel using some arbitrary allocation formula.

Nobody understands what commercial actions would be needed to generate the revenue, which customers it would come from, or which products it would involve.

As a result, the supply chain has no idea what to produce or what materials to acquire.

Another practical consequence of the annual cadence and political bargaining is that there’s not always enough time—or even a real possibility—to integrate plans across functions, even in the original process, despite the fact that it takes months.

Sure, a well-functioning process could avoid this, but most companies don’t have well-functioning processes because they’re hard to implement and sustain.

So, as a result, even the total numbers don’t match. Operations costs don’t align with sales budgets. They may have aligned at first—or ten revisions ago—but not after 20 iterations and countless ‘management adjustments.’

So yes, if you’re looking for a cumbersome tool to align people around a fixed number that doesn’t make sense to aim for in the first place—while leaving most actions misaligned and untested in practice—then yes, annual budgeting is a fantastic tool.

But if you’re looking for a way to align decisions across the company based on what’s actually happening in the real world—toward something that maximizes performance over the long term—then annual budgeting is one of the worst options you could choose.

7. Stability

Another timeless classic.

Executives sure do love their ‘stability.’

However, the reason they love it isn’t because ‘stability’ maximizes business performance. They love it because of the illusion of control and predictability it provides.

That makes their lives easier—fewer questions, less criticism about ‘what has changed’ or ‘don’t they know what they’re doing?’

And indeed, annual budgets do increase the stability of outcomes.

That’s something they are arguably great at.

But the question executives should be asking is: at what cost?

Followed by: does it even make sense to strive for ‘stability’? That is, if the goal is to maximize business performance.

The costs are high.

If the goal is to maximize business performance, stability of outcomes is one of the last thing you want.

Annual budgets bring stability in the same way that tying the rudder to the deck brings stability to a boat.

Sure, there’s stability—but also no ability to steer the boat.

This is a variation of earlier points. Stabilizing outcomes does two things:

- It inflicts all real-world variability onto actions (the opposite of stability).

- It incentivizes risk aversion.

Variability, unpredictability, and change are characteristics of the real world.

There’s nothing any company can do to eliminate them. So, while freezing expected outcomes may create the illusion of stability, in reality, it only shifts the instability into actions.

If you want to have the same exact outcome in all situations, it means you’ll have a massive amount of instability in what you have to do. In other words, the actions an organization takes will be all over the place (including not adhering to strategy).

Don’t know what that looks like? Go see what any public company obsessed with ‘hitting the budget’ at the end of the quarter does: it’s the opposite of ‘stable.’

It’s also 100% driven by ‘how to hit the budget,’ and 0% what aligns with strategy.

In addition, if stability of outcomes is what you seek or reward, that’s the same as incentivizing risk aversion. By definition.

The less risk you take, the less you innovate. The more you do things the way they’ve always been done and pursue ‘sure bets,’ the more stable your numbers will be.

They will also be more modest—and the company will make less money over time—but hey, what the h*ll. At least you have ‘stability.’

Right?

So, to summarize: using ‘stability’ as an argument for annual budgeting is indeed a great one—if what you want is average to low performance, massive organizational hassle, and no effective strategy, all while chasing numbers that shouldn’t be chased in the first place.

But if you’re interested in maximizing company performance over the long term—and having consistency and stability in what the company focuses on and actually does (i.e., executing an effective strategy), including what’s visible to customers—it’s a terrible argument.

8. Deep Dive in the Business

This is often what you get once you’ve dismantled all the previous arguments people have for annual budgeting. Even when they admit to many of its flaws and can’t find any other justification, they fall back on: “It’s nice to have a deep dive.”

Well, isn’t that wonderful.

Again, there’s some truth to this.

Sure, a deep dive into the business can be useful—and in many cases, it is.

So, that surely qualifies as a good reason for annual budgeting?

Right?

Wrong.

What people who use this argument don’t realize is what it says about their ability to run the company.

Nothing good.

The question they should be asking is this: “If you have a good understanding of the business, what relevant new information is a deep dive going to give you?

In other words, if the decisions they—and the organization—have been making throughout the year are solid, why would they need a deep dive?

What decisions are made only once a year, during annual budgeting, that require a deep dive revealing insights that somehow aren’t relevant the rest of the year?

That list is awfully short. Nonexistent, if we’re being honest. And definitely not enough to justify all the time and effort that goes into the annual budgeting process.

So yes, while an annual deep dive might indeed be useful, the real problem is that it means you don’t have sufficient understanding of what’s going on during the rest of the year—and as a result, you’re making poor decisions most of the time.

You should focus on fixing that. And once you do, your argument about needing a ‘deep dive’ as a reason for annual budgeting becomes irrelevant.

So, while you at first may have a valid argument for annual budgeting, you have a much bigger problem—one that is, in fact, the root of all your issues, including why you feel the need to run annual budgeting in the first place.

Fix that, and you no longer have a reason for annual budgeting either.

9. External Stakeholders’ Requirements

This is the last resort of true believers in annual budgeting. It has the added benefit of relinquishing responsibility. “Oh, why do we do annual budgeting? Yeah, it’s required by law. Outside of our control. Just one of those things. You know?”

When all their other arguments for annual budgeting have been shown to be without merit, this one is hard to deny, right? It’s not even up to them—it’s somebody else.

“Why are you even asking? Didn’t you know that?”

Surely, the requirements of external stakeholders justify annual budgeting?

After all, you can’t ignore them. You have a fiduciary duty to inform the markets how the company is doing.

Sure, but here’s the thing. This is just another version of the ‘need for a deep dive.’

Yes, if you have poor understanding of how the company is doing, you do need to figure that out in order to meet the requirements of external stakeholders.

And annual budgeting may indeed be the way you’ve done that for the past 50 years.

However, here’s the real question: “What information do external stakeholders require that isn’t already relevant for the organization to make great decisions?”

Again, that list is awfully short. Nonexistent, if you’re being honest.

In other words, if you constantly have a solid understanding of how the company is doing—something that’s also required to make great decisions—you can meet external stakeholder requirements at any time, without cumbersome annual reporting exercises.

So, the real problem to solve is how to improve your understanding of how the company is doing—not how to meet some arbitrary external reporting requirement.

Ironically, the main reason you need annual budgeting to meet external stakeholders’ requirements is because you run annual budgeting.

If the company ran a continuous planning process that produced a solid understanding of how the company is doing—consistently and across all time horizons—it would not only enable better decisions, it could also satisfy all external stakeholder needs without extensive annual exercises.

Conclusion

The most common arguments for annual budgeting are nonsensical:

- To Set Targets

- High Performance Standards

- Accountability

- Strategy Implementation

- Financial Decisions and Resource Allocation

- Alignment

- Stability

- Deep Dive in the Business

- External Stakeholders’ Requirements

The problem isn’t just that these arguments are nonsensical—or the negative business impacts that follow directly from believing them.

The deeper issue is that by refusing to admit the facts and ‘face the brutal truth,’ companies become unable to even evaluate whether they could be doing something better.

That said, there are also valid reasons to continue with annual budgeting, even when far superior options (for some companies and some leaders) are available.

For example: “This is how we’ve always done it.”

That’s not a joke.

While it’s arguably the worst reason to do anything, it does come with a couple of major advantages.

It requires zero time and effort to implement. It also guarantees a perfect cultural fit and carries zero risk of failure of implementation.

So, despite all of its flaws and shortcomings, annual budgeting may still be the only ‘practical’ or even the ‘best’ option for some companies.

Sure, the reasons why may be similar to why free market principles won’t work in a communistic country.

But unless executives can cut through the nonsense of the most common flawed arguments for annual budgeting, they can’t even have a rational discussion about what’s the best way to run their businesses.

And if they can’t have a rational discussion, they can’t make rational decisions either.

Practical insights

- Many executives can’t discuss reasons for annual budgeting rationally.

- Annual budgeting produces targets disconnected from real performance.

- Annual budgeting enforces accountability where it doesn’t belong.

- Annual budgeting results in low, not high, performance standards.

- Annual budgeting is one of the worst tools for strategy implementation.

- No company needs annual budgeting to make financial decisions.

- Annual budgeting creates misalignment, not alignment.

- Annual budgeting stabilizes outcomes by destabilizing actions.

- Deep dives are only useful when decision-making the rest of the year is poor.

- Annual budgeting is not required to meet external stakeholder needs.