Introduction

Everyone’s lying. Sales, Supply, Finance—they all know the numbers aren’t real. But no one says it out loud.

End of the quarter. Forecast: 100. Actuals: 90. The blame game begins.

- Finance blames Sales for missing the budget and Supply for high inventories.

- Sales blames Supply for not delivering—and Finance for an unrealistic budget.

- Supply blames Sales for inflated forecasts and Finance for too tight inventory targets.

Here’s how they got there.

Finance pressures Sales to “hit the budget.”

Sales doesn’t know how—because the budget isn’t real. To keep Finance off their back, they match the forecast to it, then inflate it to Supply to secure availability.

Supply doesn’t buy it. The numbers have no logic, and Finance is also pushing them to cut inventory—so they cut the forecast.

End of the quarter: Sales miss forecast, inventories are still too high—because Supply’s cuts weren’t tied to real demand. Finance, fixated on the gap to budget, pushes Sales harder to close it, while pressing Supply to meet working capital targets.

Sales—knowing Supply will cut their forecast—responds by inflating it further.

Supply, facing another inflated forecast, cuts even deeper. Production drifts further from demand.

End of the month: more missed sales, more wrong stock. Everyone blames each other. The cycle repeats.

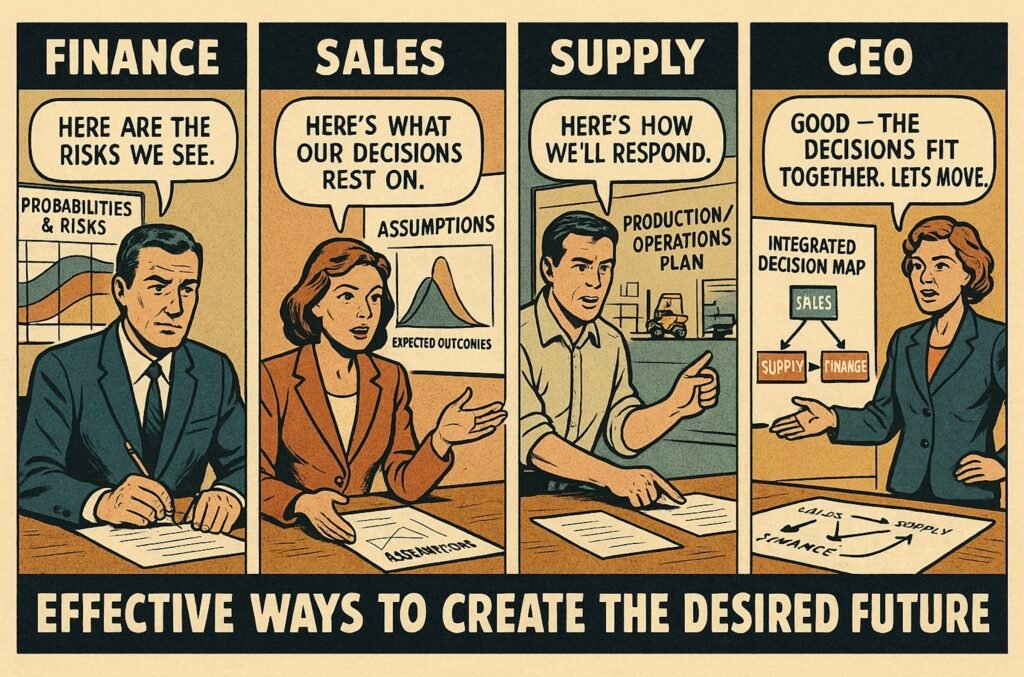

This article explains why that pattern is so common—why, despite each function trying to do its job, none can fix it alone—and what the real solution is.

Like most planning failures, this is a leadership problem. Only the person running the company can fix it.

But first, they have to understand what the problem actually is.

The Problem

At first glance, it seems the problem is that forecasts differ from actuals. That assumes the gap reflects a failure in performance. But that’s not necessarily true.

Neither is the gap the real problem. The numbers compare two fixed points in time, but they hide the real issues—and the real performance.

1. Hidden Performance Gap —The odds are that forecasts and actuals compare what performance probably shouldn’t have been with what it probably wasn’t—not real performance.

2. Hidden Decision Impacts — It’s assumed Sales, Supply, or Finance failed—but there were no clear expectations for how they should have performed. The logic and expected results of their decisions are hidden.

3. Lack of Alignment — Even if expectations about decision impacts exist, their effects on other stakeholders—or the whole—aren’t aligned in advance. Misalignment is only discovered after execution.

4. Distorted Accountabilities — Even when stakeholders are aligned, no one is held accountable for the quality of their decisions. Instead, they hide behind collective outcomes and blame each other.

5. Hidden Uncertainty and Risks — It’s hard to hold people accountable for their decisions in a probabilistic world with deterministic tools. Outcomes depend on uncertainty and luck, and the trade-offs are poorly understood.

6. Distorted Incentives — Stakeholders hide decision odds and risks because they can use them to their advantage, since they are incentivized to hide the truth, distort results, and suboptimize silos.

7. Flawed Targets — Distorted behaviors are often driven by targets disconnected from reality. They ignore uncertainty, difficulty, and decision impacts—and fail to represent a meaningful future the company wants to become.

8. Ineffective Learning — The problem isn’t just that the company has issues with how it makes decisions. The bigger problem is that it has no capability to effectively learn how to improve.

9. System Failure — The problem isn’t any of these problems alone. It’s how they work, or don’t work, together: as a system not able to support effective decision-making.

10. Leadership Failure — The decision-making system is how it is because it always reflects how the CEO leads—or what they tolerate.

Main Problem: Ineffective Ways to Create the Desired Future—The real issue isn’t that forecasts and actuals differ. It’s that the company can’t make decisions that effectively create the future it desires.

1. Hidden Performance Gap

A forecast of 100 and an actual of 90 suggests a performance gap of 10. But that doesn’t necessarily mean performance fell short of expectations.

Why?

- The forecast doesn’t represent what performance should’ve been.

- The actuals don’t represent what performance was.

Forecasts often carry systematic error—shaped more by politics, buffers, and incentives than grounded assumptions about the real world like market growth or product launches.

So even if decisions were sound and execution solid—i.e., performance went as expected—the outcome still wouldn’t match the forecasted 100.

Even a forecast of 100 based on solid assumptions is just a point estimate in a probabilistic world. The odds of landing exactly on 100 are near zero.

Put differently: even if performance is as expected, you should still expect the outcome to differ from 100.

So when there’s a gap of 10, how much reflects real performance—and how much is just dumb luck?

Actuals can’t answer that. The number may be correct—but also misleading.

It can include gimmicks or short-term moves that create the illusion of performance without actually improving it—and sometimes even making it worse.

For example, pushing product into a customer’s warehouse might raise actuals from 80 to 90. But if it just shifts timing between quarters—and comes with a 10% discount—it hasn’t improved real performance.

So while 90 shows the ability to hit a number, it may misrepresent performance.

Of course, it depends on how you define performance. If it means stability of outcomes, 90 counts. If it means achieving real results over time, like growing sales or profits, 80 reflects actual performance—and 90 an illusion.

Bottom line: forecast vs. actuals often compares “what performance probably shouldn’t have been” with “what it probably wasn’t.”

Acting on that gap risks punishing good decisions with bad outcomes and rewarding bad ones with good luck—which hinders performance.

This happens because the real decision impacts are hidden.

2. Hidden Decision Impacts

It’s hard to say afterward who didn’t perform as expected—Sales, Supply, or Finance—because there’s often no clear expectation for how each should have performed.

That’s because individual and overall expectations are conflated.

Company-wide figures—like $100M in EBIT, $1B in sales, $100M in inventory, or a 98% service level—reflect overall outcomes, not function-level expectations. They show the combined effect of everyone’s decisions.

Take a forecast of 100 for actual sales. What does it actually represent?

actual sales = unconstrained demand ∩ supply

Unconstrained demand is what customers would buy, regardless of supply capabilities—as a result of Sales’ decisions (for example: hiring 100 reps, raising prices, or targeting large customers).

Supply is what’s actually available to be sold—as a result of Supply’s decisions (for example: hiring factory staff, increasing safety stock, or relocating inventory).

Actual sales are the result of both. Not just what customers want. Not just what’s available. Only where the two align.

But companies rarely forecast (what they think will happen as a consequence of their decisions) unconstrained demand or supply. So the impact of individual decisions—and the assumptions each function makes about the others—stays hidden.

Sales and Supply end up planning based on actual sales, which means they’re implicitly forecasting the impacts of each other’s decisions.

- Sales’ choices—like hiring 100 reps, raising prices, or targeting large customers—shape demand’s volume, timing, and mix.

- Supply’s choices—like hiring factory staff, increasing safety stock, or relocating inventory—shape supply’s.

Each function, then, evaluates performance using assumptions about the other:

- Sales’ expected actual sales =

Sales’ assumption of unconstrained demand ∩ Sales’ assumption of supply

- Supply’s expected actual sales =

Supply’s assumption of unconstrained demand ∩ Supply’s assumption of supply

Unless:

- Sales and Supply’s assumptions about demand match

- Sales and Supply’s assumptions about supply match

…you wouldn’t expect actual sales to match either expectation—even if both did their job well.

Finance is no different. Its financial expectations are often built on its own assumptions—not those of Sales or Supply. When it cuts budgets, it implicitly assumes how that will affect unconstrained demand or supply.

The target impact—say, $5M in savings—may be clear. The effect on decisions, and from there on actual sales, usually isn’t.

So even if every function performs as expected, you still wouldn’t expect actual sales to match any of their expectations.

The performance debate at the end of the quarter isn’t a one-off misunderstanding. It’s the result of structural misalignment.

3. Lack of Alignment

Extensive debate after the fact signals a lack of alignment in advance.

The issue isn’t just who didn’t perform as expected—it’s that the impacts of Sales’, Supply’s, and Finance’s decisions on each other, and on overall performance, weren’t understood to begin with.

That’s not the same as predicting outcomes precisely. That’s a straw man. The real problem is that even when everything goes as expected, the interdependencies—and their effect on the whole—often aren’t factored into decision-making.

Put simply: if the forecast was 100 and actuals came in at 90, the entire gap could stem from not understanding how decisions interacted.

Even with a perfect item match, a mismatch of 10 could occur—if demand came from large customers needing factory shipments, but supply was set up for small customers at local warehouses.

The problem is not that the numbers or assumptions don’t match. It’s the failure to understand what matters for others’ decisions.

Supply can flex volume short term with overtime, medium term by hiring, longer term by adding lines, and radically by building new factories.

Sales can flex short term with promotions, medium term by hiring or closing large deals, long term through new channels or markets.

But alignment can’t stop at volume. A flat 100 across time buckets demands different choices than a spike to 100 at quarter-end.

The right level of detail depends on the decisions. A factory build might require annual volume; warehouse operations might need weekly or even daily granularity.

Too little detail leads to misalignment—and blame after the fact. Too much creates bureaucracy, inefficiency, and rigidity.

Mix matters too. Sales shapes it through targeting, pricing, and promotions. Supply shapes it through sequencing, safety stock, and replenishment.

Even with 200 in capacity and 100 in demand, Supply can still be constrained—if the mix skews toward products it’s not set up to produce (e.g., newer vs. older SKUs).

The relevant level of detail is always company-specific. The problem isn’t nailing the “right” level of detail—it’s failing to identify what matters, or improve that understanding over time.

Lack of alignment doesn’t mean that the numbers don’t match.

First, because of uncertainty, constraints, and lead times, actual sales of 100 might require unconstrained demand of 105 and supply of 120—even in a “perfectly” balanced scenario. In practice, 100 ≠ 100 ≠ 100.

Second, if unconstrained demand is 105, Supply doesn’t have to plan for 105. It might plan for 140—based on a forecast of 120—because it’s managing different risks.

“Doesn’t that lead to higher inventories?”

Probably. And it might still be the better decision. (More in Hidden Uncertainty and Risks.)

So why isn’t there alignment in advance?

Because no one is held accountable for the impacts of their decisions—and misalignment often serves individual interests.

4. Distorted Accountabilities

Lack of alignment is often a symptom of distorted accountabilities.

When the real discussion happens after the fact—and stakeholders dodge ownership—it’s a sign they don’t own their decisions. And they can’t be held accountable for them.

Sales, Supply, and Finance are typically held accountable for targets (what we want to happen)—not for their decisions (what they will do) or the forecasts those decisions are based on (what they think will happen).

In other words, they’re accountable for outcomes (which they don’t control)—but not for how they try to achieve them (which they do control).

That means they aren’t accountable for how their decisions affect others or the whole. Nor are they accountable for whether their forecast—what they think will happen, the story they tell—is grounded in reality or good judgment.

This is why Sales can tell Supply they expect demand of 130, based on nothing, when they actually expect only 100. The forecast doesn’t reflect real decision impacts or real performance. It reflects how the game is played.

And the game isn’t about maximizing total performance—it’s about maximizing the odds of hitting your own target, even when that target isn’t worth hitting in the first place.

For example:

- Sales may be accountable for hitting a target of 100, but not for whether their unconstrained forecast of 130 to Supply reflects what they actually expect—or whether it drives excessive inventory.

- Supply may be accountable for an inventory target of 20—but not for whether the forecast they use reflects Sales’ forecast, or whether it causes lost sales.

- Finance may be accountable for an EBIT target of 10, but not for whether their cuts reflect what Sales and Supply think will happen—or what those cuts do to future sales or service.

When there’s accountability only for the target and not the forecast, the two often become the same. That sounds clean—but in a probabilistic world, it’s never true.

Instead, it hides what anyone actually thinks will happen. And while the target may be what matters in the end, all decisions depend on forecasts—on predictions about decision impacts, not on the target itself.

Performance is always managed against the forecast:

- Looking backward: how actuals differ from what we thought would happen

- Looking forward: how what we think will happen differs from the target

If the forecast contains a systematic error, so does the understanding of performance. You’re stuck managing performance between:

- Looking backward: how actuals differ from how the game is played

- Looking forward: how the game is played differs from the target

The real problem? It’s hard to evaluate whether decisions were good—or how to make better ones. In other words, there’s no accountability for decision quality.

And there is often no real accountability for the long-term effects of decisions, beyond the current calendar year. That biases decisions toward short-term outcomes at the expense of long-term performance.

Targets don’t create accountability—they create theatre.

Cassie Kozyrkov nailed it: confusing outcomes with decision quality is “one of society’s favorite forms of mass irrationality.”

Even if you hit the outcome, it doesn’t mean the decision was good. Same logic as the forecast–actuals gap: the difference might be dumb luck.

That’s not even counting how easy it is to game the number. Which is the other reason actuals don’t always reflect real performance.

And this holds across all decisions and outcomes. From outcomes alone—hit or miss—you can’t tell how good the decisions were.

Even if you could, “accountability” is the wrong word. Meaningful targets—sales, profit, inventory—depend on multiple stakeholders. No single function truly owns them.

That’s how they behave, too.

When Supply constrains the outcome, Sales doesn’t take accountability for the lost sales.

More likely: “We would’ve hit the number—if only Supply had delivered.”

That’s not accountability. That’s deflection.

Same with Supply.

When Sales’ forecast misses, Supply rarely takes accountability for inventory or service.

More likely: “Our KPIs would’ve been fine—if Sales had gotten the forecast right.”

Again, not accountability—just blame in disguise.

And Finance? CFOs rarely take accountability for the side effects of their own cuts.

More likely: “Sales was soft. Supply had issues.”

That’s managing the message, not being accountable.

Why do companies prefer target-based accountability over decision-based accountability?

Because they have ineffective ways to manage uncertainty and risk.

5. Hidden Uncertainty and Risks

The problem with expressing expected outcomes—like sales—as deterministic point estimates (e.g., 100) is that the underlying uncertainty is hidden.

When Sales says expected actual sales are 100, what they really mean is there’s some probability that sales will exceed 100.

There’s virtually a 0% chance sales will be exactly 100—but maybe a 50% chance of exceeding it, or a 90% chance of landing between 90 and 105.

Without explicit probabilities, you can’t effectively evaluate performance, align stakeholders, or hold anyone accountable for the impacts of their decisions.

Hidden uncertainty leads to misinterpretation. The CEO may treat the 100 as a promise. Supply may see it as a 50/50 scenario. Sales might treat it as a P10—only a 10% chance—because it matches the budget, not reality.

This is why companies struggle to align Sales, Supply, and Finance. They’re trying to agree on the “right number”—which only makes sense if you ignore uncertainty.

Once you acknowledge it, it’s obvious: there is no “right” number.

As noted in Lack of Alignment, Sales and Supply can still be aligned even if they use different numbers—Sales expecting 105, Supply planning for 120—if those reflect different probabilities of the same distribution. Sales might use a P50; Supply might plan for a P20.

Supply has longer lead times and must commit early to avoid stockouts. Sales has more flexibility, so it centers closer to the median. The company accepts higher inventory and holding costs to reduce the risk of lost sales and service failures.

Trying to align on one number flattens these trade-offs. It ignores lead times, constraints, and decision flexibility—forcing functions into worse decisions.

It also makes it harder to revise unrealistic targets. If all you have is one number, it’s always “still possible.” The assumptions change, but the number doesn’t—so it becomes a timing story: “It’ll turn around in Q4.”

You can’t say the target won’t be hit for sure—but you also can’t see that a P50 has become a P30. That leads to chasing goals no longer worth pursuing—and reviewing performance without context. You’d expect to hit a P50 half the time. A P30? Only 30%.

Decision-making in business is inherently probabilistic. Forecasts, assumptions, and decisions all carry uncertainty. The only question is whether it’s acknowledged—or ignored.

As Charlie Munger put it:

“If you don’t get this elementary, but mildly unnatural, mathematics of elementary probability into your repertoire, then you go through a long life like a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest. You’re giving a huge advantage to everybody else.”

The only differences are how explicit the probabilities are, how aligned stakeholders are on them, and how well their implications are understood.

Deterministic numbers are to expected outcomes what arithmetic without multiplication is to mathematics: an incomplete tool for the job.

Even if Supply is “just right” for demand of 100, if that demand is a P50, there’s still a 50% chance inventories will exceed expectations.

And Supply is uncertain too—due to quality issues, machine failures, material delays, or strikes. A plan for 100 might be a P50—or a P90—depending on context.

Because both demand and supply are probabilistic, so are outcomes: actual sales, inventory, service levels.

There’s no “right” demand or “right” supply that guarantees specific outcomes.

There’s only: given this demand and this supply, there’s some probability that sales exceed 100, inventory drops below 20, or service hits 98%.

Once you see this, it’s clear: there are no right answers—only risks to manage.

And those risks are often hidden too. It’s unclear what risks were taken, who took them, when, where, or based on what logic.

So it becomes impossible to assess—after the fact—how much of the outcome was due to calculated risk (i.e., performance as expected), and how much came from poor decisions or weak execution.

It also means people can take risks without owning the downside—but still benefit from the upside.

For example, when Sales gives a P10 forecast of 130 to Supply to avoid stockouts, they’re taking a 90% risk of excess inventory.

When Supply cuts that to 100 at P50, they take a 50% risk of missing demand. Or when Finance tightens budgets to raise EBIT certainty to P90, they may shift the P50 demand forecast to P40, and supply to P30—lowering the odds of meeting either.

In Excel, using point estimates, it still looks “in balance.”

And technically, it is—nothing rules out hitting all targets. But the probability may have quietly dropped to 10%. In other words, Sales, Supply, and Finance are “executing” a P10 plan.

Put simply, in 9 out of 10 cases, you wouldn’t expect those deterministic outcomes to hold. Which means that in 9 out of 10 “performance” reviews, they’re judging noise—variations irrelevant to actual performance.

The ability to take risk without consequence creates a negative spiral—especially when objectives conflict and no one owns the whole picture.

One-sided risk-taking isn’t a failure of effort. It’s a failure of structure.

Risks aren’t aligned upfront. They’re only debated afterward, as “surprises”—even when they were predictable. Performance suffers.

Put differently: hidden risks that shift consequences onto others create incentives that quietly undermine performance.

Not because anyone is malicious or incompetent—but because they’re incentivized to behave that way.

6. Distorted Incentives

Executives reward behaviors that lead to gaming and poor outcomes, while punishing those that would lead to higher decision quality and performance.

They wonder why Sales, Supply, and Finance are misaligned, or why forecasts diverge from actuals—without realizing the incentives are designed to produce exactly that.

Expecting people to ignore their incentives “for the good of the company” is the same flawed thinking that brought down communism.

Why does Sales exaggerate demand?

Because bonuses depend on hitting fixed, year-end targets—not telling the truth. Overstating demand improves their odds of “winning” in their silo.

Why do business units sandbag?

Because they’re rewarded for beating expectations—not for showing how the business is really performing.

It’s not contradictory to exaggerate in some cases and sandbag in others.

Both are not only rational but inevitable in a system that doesn’t reward cross-functional cooperation.

- Sales has no incentive to give a realistic demand forecast to Supply and Finance.

- Supply and Finance have no incentive to take it seriously.

Each function exploits information asymmetry to protect its own position—hiding risks, uncertainty, and decision impacts from others. Each function has its own version of the truth—sometimes several—depending on who asks.

Performance is measured one way, while decisions are made another—on different assumptions and timelines. That makes hiding the real impacts of decisions rational.

Development follows the same logic: each function improves its part, regardless of whether the pieces fit together.

Leaders say they want risk-taking, but the system punishes it.

Targets ignore difficulty—and how difficulty shifts with uncertainty. If you understand the odds better than others, you can game them. It’s like running a sportsbook where you set the odds and the bettors know less than you.

Management judges outcomes, not decisions. Hitting the number is success; missing it is failure—regardless of context. That bias rewards risk aversion.

You have endless ways to game your slice for personal gain—but almost none to improve the long-term performance of the whole. The real incentives? More headcount. More budget. More turf. Not better decisions. Not better performance.

The problem isn’t a single flaw like short-termism, siloed thinking, or misaligned rewards.

It’s how they reinforce each other. Suboptimization fuels short-termism. Short-termism drives gaming and distortion. Distortion destroys alignment, which in turn reinforces suboptimization.

It’s a catch-22: to create incentives that reward long-term, cross-functional performance, those very incentives would already need to be in place.

Instead of surfacing problems early and fixing them, the system rewards hiding gaps and punishes truth. And nothing distorts incentives more than flawed targets.

7. Flawed Targets

Most targets don’t describe a meaningful future the company intends to become; instead, they reflect arbitrary numbers that may or may not make sense to “hit.”

Often they don’t.

Take financial targets like “$1 billion revenue by 2027” or “$100 million EBIT this year.” They describe arbitrary outcomes—not what the company will become.

You can hit $100 million EBIT by selling budget or premium products, with or without a strategy, to anyone or everyone, with or without long-term focus.

That flexibility may help hit the number—but often at the cost of long-term performance.

Trying to be everything to everyone usually ends up being nothing to anyone. To become something specific requires real choices; numbers alone don’t force it. That’s why strategy experts emphasize integration of decisions—focus and fit.

Of course outcomes matter. But targeting them directly is ineffective—because they don’t define what the company is becoming. You can’t reverse-engineer performance from a number—especially when that number isn’t tied to real decisions about what to become.

Worse, most targets are tied to the calendar year—an arbitrary timeframe. They’re disconnected from real decision timelines and unreliable as performance signals.

Big choices—product launches, market entries, capacity bets—play out over years. Their impacts don’t fit inside a 12-month window—yet that’s the frame targets force them into. So even good decisions are penalized in the short term.

It’s a structural mismatch: decisions shape long-term outcomes, but targets steer short-term.

And none of that accounts for uncertainty.

Targets are usually deterministic point estimates. They assume a specific result in a probabilistic world. A $100 million EBIT target might start as a P70, but shifting assumptions could turn it into P50 or P90—without anyone realizing the odds have flipped.

Yet bonuses and evaluations are still tied to that static number. If it becomes impossible, leaders chase it anyway. If it becomes easy, rewards still flow. Perception beats performance.

This distorts behavior. Stretch targets raise the odds of missing and losing rewards. Conservative ones protect bonuses. Risk aversion becomes rational—even when calculated risk taking could improve performance.

Ignoring probabilities also leads to short-term bias in target setting. People think it’s impossible to set targets for the next 3–5 years because “anything can happen.” And they’re right—it is difficult to set effective deterministic targets that far out.

It also leads to rewarding and punishing dumb luck. A team might miss a stretch target despite great execution. Another might beat an easy one through luck. But the system can’t tell the difference.

The real problem isn’t just the targets—it’s how they’re set. Annually. Politically. Disconnected from decision-making. The debate is about numbers, not about what the company wants to become. Target-setting becomes a negotiation over who gets what—not how to improve performance.

And the targets don’t just distort behavior—they block learning. If a target doesn’t reflect a real probability and a decision logic, then hitting or missing it teaches little from the real world.

If there’s any learning effect, it’s learning how to game the system—not how to make better decisions.

8. Ineffective Learning

Recurring blame game about the gap between forecast and actuals signals inability to learn effectively.

In other words, the company is either unable to identify how the logic in “what it thinks will happen” differs from reality, or unable to apply those learnings to revise it.

For example, a forecast of 100 might be based on a decision to increase prices by 5% and an assumption of 10% market growth.

But when actuals come in at 90, the company fails to recognize that prices rose only 3% and the market grew just 5%—and doesn’t use that information to update the forecast.

That may have happened because the forecast of 100 wasn’t grounded in real assumptions to begin with—due to Hidden Decision Impacts, driven by Distorted Incentives.

Or it might also happen because the company doesn’t consider that there’s anything to learn. If Q2 misses forecast, the response is often to push harder in Q3—as if the Q2 forecast of 100 was correct and now needs to be made up.

Even when logic exists and differences are visible, people avoid revising it—because updating a forecast is seen as failure, treated by executives as breaking a “promise.”

So the numbers stay frozen, even when reality moves. Everyone’s “surprised” by what they already knew.

“Why did actuals differ from forecast?”

Because the market grew 5%, not 10%, and prices rose 3%, not 5%—just like last quarter.

Moreover, since outcomes are probabilistic and distinct from decision quality, even forecasts based on sound assumptions are hard to learn from. Good decisions can still produce bad outcomes, and bad decisions can sometimes produce good ones.

This distinction is rarely understood, and companies lack tools to make it. Even when people try to learn, they can’t separate decision quality from random noise—so responses often overreact to chance events.

As a result, companies end up changing good decisions after bad outcomes, and clinging to bad decisions after good ones.

The focus shifts to smoothing the numbers instead of improving decisions. It creates a dangerous illusion: performance looks managed, but in reality only the numbers are being managed.

And none of it improves the one thing you can manage: decision odds.

If you’re not learning how your decisions shape risk, you’re not managing uncertainty. And if you’re not managing uncertainty, you’re not improving performance.

That’s the real issue.

The problem isn’t that forecasts differ from actuals—it’s that the company has no effective way to learn from the gap.

9. System Failure

The problem with these issues isn’t any one in isolation—it’s what they reveal collectively: a broken decision-making system.

It’s not just one part—Hidden Decision Impacts, Lack of Alignment, Distorted Accountabilities, etc. It’s not even their sum. It’s how they interact and reinforce each other—how they work together.

Decision impacts stay hidden because incentives reward hiding them. Hidden impacts make alignment impossible. And even if incentives existed, the capability wouldn’t—because uncertainty is unmanaged and risks are hidden.

Stakeholders also benefit from hiding probabilities, risks, and decision impacts—because it lets them game the system. They can improve the odds they appear to perform well, or at least avoid looking like they failed.

All of this is possible because the company has no effective way to learn. There is not only no mechanism, but no incentive either—since leadership treats changing forecasts or revising targets as failure.

That means decisions are steered toward flawed targets—often impossible to hit without manipulating results or exaggerating capabilities. Which, in turn, reinforces the hiding of decision impacts, probabilities, and risks.

The cycle feeds on itself.

Put differently, the issue isn’t how to get the organization to work better within the current system—it’s how to build a better system the organization can actually perform in.

But fixing the system isn’t as simple as tweaking one part. Nor can any individual function—Sales, Supply, or Finance—fix it. They don’t own the whole, and they don’t control incentives, leadership, or governance.

The absence of system ownership leads to workarounds: Finance builds new FP&A processes. Supply pushes S&OP. But none of them can fix what they don’t own.

System problems aren’t about individual parts—they’re about how the parts work together. And improvement always depends on the bottleneck.

For example, what looks like misalignment may really be an incentive problem—driven by flawed targets, which reflect leadership behavior and system design.

And system change isn’t a technical fix. It takes time, money, and effort—and often requires changing how decisions are made, who makes them, and who holds power.

That brings political complexity. So even when the system is clearly broken, the typical response is to adjust a few parts—because it’s safer and easier than changing the whole.

As a result, decisions get made to balance political interests—not to build an effective decision-making system.

That’s why the way a company is steered always reflects how the CEO chooses—or is able—to lead.

So the real question isn’t what the system should look like, but how the CEO wants to lead.

10. Leadership Failure

The problem with an ineffective decision-making system isn’t that it falls short of some theoretical ideal. It’s that it reflects how the CEO chooses to lead.

The system doesn’t lack learning or visibility because those are technically hard problems. It lacks them because the CEO defines performance as hitting a static annual number, expects every forecast to show how it will be hit, and treats changes as failure.

That kills any incentive to produce a truthful forecast—or to build a system that could. Instead, the system is built to tell the CEO what she wants to hear: stable, reassuring numbers—whether they reflect reality or not.

Likewise, probabilities and risks aren’t hidden because there are no tools to handle them or people couldn’t learn to use them effectively.

They’re hidden because the CEO doesn’t use them—and doesn’t expect her team to either. The system can’t tell a 60/40 bet from a 40/60 bet because the CEO can’t—and doesn’t see why it matters.

So the forecast isn’t a view of reality. It’s a distorted mirror of the CEO’s expectations—systematically biased to match an outcome that feels safe, not one that reflects what’s likely or what’s needed.

And that’s a leadership failure—because the company’s view of “what will happen” is distorted. It can’t effectively make good decisions or learn to improve.

Only one role is accountable for that: the CEO. Not Sales. Not Supply. Not Finance. The CEO owns the system the company uses to steer—and is the only one with the authority to change it.

But most don’t. They stay detached from forward-looking steering—claiming it’s “too operational,” or “you cannot predict the future”—while diving deep into backward-looking budget variances and daily sales reports.

That might create short-term control. But it also locks in the system that prevents better decisions—and with them, long-term performance.

The disconnect is simple: the outcomes the CEO wants—higher growth or better returns—are far less likely under the way they lead.

Growth requires risk. Risk brings variability. And variability is punished in systems built on deterministic control—where every decision is expected to “hit the number.”

In that environment, no one wants to place a 60/40 bet—because even winning 6 out of 10 looks like failure 4 out of 10 times.

So the company plays it safe, even when the safe choices hinder performance.

In addition, CEOs often refuse to take accountability for the system they’ve created—not for how it works, not for what it forces teams to execute within, and not for the cross-functional trade-offs it ignores, like where to take risk: lost sales or tied-up capital.

In other words, they’re playing the same end-of-quarter blame game as Sales, Supply, and Finance are playing.

One common workaround is “shared accountability”—making multiple functions jointly responsible for things like forecast accuracy or inventory turns. It sounds collaborative.

In practice, no one’s accountable. And it misses the point: there’s already a role accountable for the whole—the CEO.

If shared accountability worked, we wouldn’t need a CEO. Sales, Supply, and Finance would just coordinate and solve it. But that’s not how companies—or people—work. That’s why the CEO role exists.

What often looks like a missing technical mechanism—like a way to evaluate trade-offs—isn’t missing by accident. It’s missing because the CEO doesn’t want one, or doesn’t believe that’s how decisions should be made.

So forward-looking decisions are broken. Risks aren’t made explicit. Trade-offs aren’t discussed. And uncertainty is left unmanaged—until it shows up as a variance, after it’s too late to do anything about it.

Then the same dysfunction repeats.

The real problem isn’t that the system is flawed.

It’s that it reflects a leadership style that can’t effectively create the future it desires.

Main Problem: Ineffective Ways to Create the Desired Future

The problem isn’t the gap between forecast and actuals—it’s that the desired future is unclear, and the company has ineffective ways to create it.

Companies stuck in endless forecast–actuals debates usually lack a meaningful aspiration for what they want to become. And even when they do, those aspirations are suppressed by arbitrary financial targets, like “hit $1 billion in revenue.”

They start with numbers, then try to decide what business they should be in.

That’s backwards.

Financials are outcomes—of strategic choices, resource allocation, execution, and luck. Numbers assume everything and nothing at once: everything, because they embed assumptions about decisions; nothing, because the same target could be hit in countless ways.

Worse, the way companies chase those numbers is broken by design.

They steer decisions based on outcomes they don’t control, while ignoring decision quality—the one thing they can influence. They divide the whole into parts, lock targets and resources through politics, then measure performance by parts instead of by the whole.

The result is that massive effort goes into gaming the system instead of improving it. Much of “performance management” is about sustaining the illusion of performance, not actually driving it.

Many companies prize stable predictable outcomes over real performance—yet still claim performance is the goal. That’s a Type III error: solving the wrong problem.

A forecast differing from actuals could mean the forecast was poor, the performance was poor, or neither. So what’s the real problem?

When the problem is misunderstood, no solution—however well-intended—can deliver results. At best, it wastes time. At worst, it makes things worse.

For example, creating new processes or buying new software to force stakeholders to ‘align’ on a single demand number—90, 100, or 110—misses the point. There is no such thing as the “right” number if the goal is better performance.

Chasing precise outcomes makes forecasts worse, not better—and in a probabilistic world, it kills performance by trading decision quality for random noise.

So the gap between forecast and actuals is not the problem. It’s a symptom.

It’s an expected result of ineffective ways to create the desired future.

Conclusion

Recurring forecast vs. actuals debates happen because companies mistake symptoms for the problem.

They fixate on forecast accuracy, missed outcomes, or siloed issues—like poor alignment or hidden decision impacts—while ignoring how the decision-making system actually works, or how it reflects the CEO’s leadership.

They don’t see that the system itself is flawed. Biased forecasts, missed targets, and quarter-end blame games aren’t surprises—they’re exactly what the system is expected to produce.

These aren’t forecasting or execution failures.

They’re signs of ineffective ways to create the desired future.

Part 2 shows how to fix that.

Practical Insights

- Forecast vs. actuals distorts the real performance gap.

- Hidden decision impacts prevent cross-functional alignment.

- Misaligned decisions end in blame games after the fact.

- No ownership of decisions encourages hiding their impacts.

- Hidden uncertainty turns identifiable risks into “surprises.”

- Distorted incentives drive dysfunction and gaming.

- Flawed targets create distorted incentives.

- Lack of learning amplifies the issues.

- These are symptoms of a broken decision-making system.

- Every system reflects how the CEO leads—or what they tolerate.