Introduction

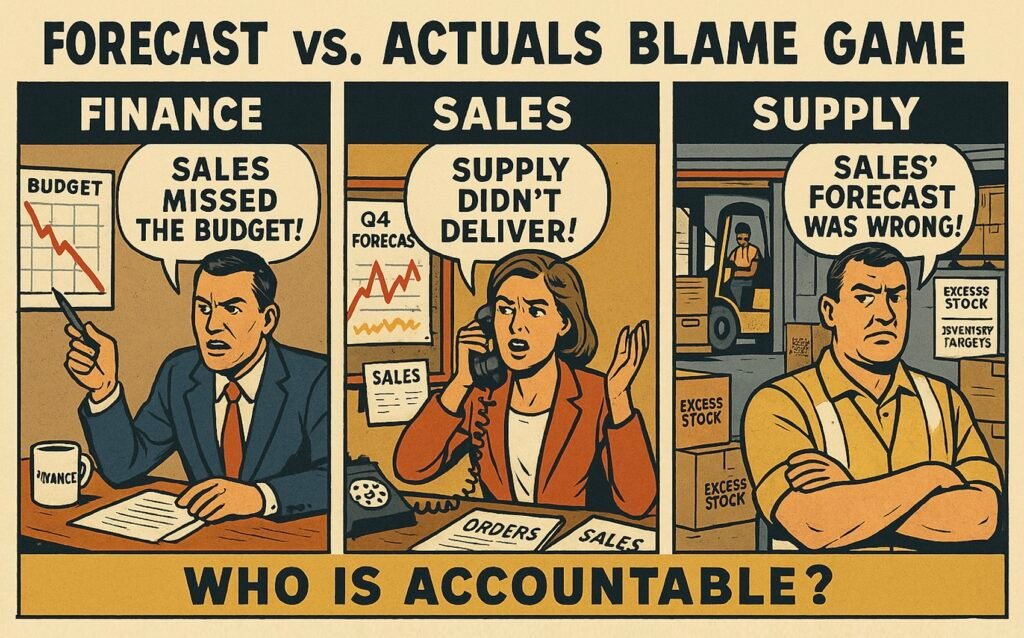

If your forecast vs. actuals debates keep coming back every quarter, the problem isn’t the forecast. It’s how decisions are made.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. You don’t need to read Part 1—but unless the real problem is understood, the solution here will seem like overkill.

And it is—if you’re fixing symptoms instead of causes.

That’s the trap. The fixes that feel most practical usually just make the symptom more manageable. They don’t make the business better at creating the future it desires.

It’s no different from trying to get in shape with crash diets, workout plans, or—God forbid—some new gadget. Even if they work, they don’t fix the real issue: how you live.

Business is no different. A new software platform, S&OP process, or xP&A model might help with real symptoms:

But they rarely fix the real problem: how decisions are made.

Some fixes even help forecasts match actuals. But if that doesn’t lead to better decisions—or closer to the desired future—what’s the point?

At best, it wastes time and money. At worst, it reinforces the illusion of control—while performance stagnates.

The solution here isn’t built on acronyms, tools, or leadership fads.

It’s grounded in first principles: how the world works, how decisions shape outcomes, and how the pieces fit—regardless of the frameworks or tools you use, or what you choose to call them.

Solve the Right Problem

Continuously diagnose the real problem—because the bottleneck keeps moving. Solving the wrong one wastes time, money, effort—and credibility.

A Type III error—solving the wrong problem—is the most common and most costly.

If the forecast is 100 and actuals are 90, ask: was the forecast off, or was performance poor? In a probabilistic world, those are different problems.

To maximize performance, you have to accept variability.

The more stability you demand, the more performance you’ll sacrifice. Reality is probabilistic—not deterministic—and higher returns require higher risk.

If someone insists on both, you have two options: help them understand why that’s not possible—or change the person. If neither is possible, walk away from the problem—and the “solutions” that follow.

They’ll waste time, burn money, and end in disappointment.

This is not a process problem—it’s a leadership-fit problem.

Some CEOs prefer the illusion of control—that actuals will match the forecast—even if it hinders performance. Others focus on making the best decisions and accept risk and variability.

Different problems demand different steering models—some require tighter control, others greater adaptability. Until the real problem is clear, the right solutions won’t be either.

If the goal is to hit fixed numbers—like $1 billion in annual sales—annual budgeting can work. It aligns decisions to the number, even if that means gaming it.

But if the real challenge is long-term growth, a different system is needed—one that tracks decision impacts over time and avoids rewarding short-termism.

That’s why rolling forecasts and S&OP often disappoint. They get stuck in short-term reporting, skewed toward Finance or Supply, with little impact on decisions or long-term performance.

At any time, only one constraint limits system performance. That constraint moves—and must be re-identified continuously.

Early on, it might be hidden decision impacts—no visibility into what Sales decided or what outcomes are expected. Once that’s fixed, it could shift to alignment: how do Sales’ decisions to push new products align with Supply’s decisions to invest in legacy capacity?

Joint meetings might help—but not if incentives still push each function to hit static targets instead of driving long-term growth. The next constraint might be leadership itself.

Each fix reshapes the system. You can’t hold people effectively accountable without visibility into decisions. But you won’t get visibility without accountability. It loops.

Fixes become whack-a-mole: improve visibility, and the next constraint appears—incentives that punish truth-telling.

Most stakeholders miss this. They chase the first problem they see—like forecast misses—and try to fix it by improving forecast accuracy. That’s the trap: the real constraint has already moved.

The right question is always: where’s the bottleneck now? It’s like Where’s Waldo—you’re staring right at it and still miss it.

Even if leadership is ultimately the issue, it’s not the first thing to fix if decision impacts still aren’t visible.

That’s why so many software rollouts flop: by the time they land, the real constraint has already moved—to incentives, planning logic, or leadership itself.

The first step in solving the forecast vs. actuals dilemma is to keep asking: what’s the right problem to solve right now (see Part 1)?

The Solution

The solution has to fit how the CEO actually leads. If it doesn’t, decisions won’t improve—and if decisions don’t improve, neither will performance.

1. Match Leadership with the System

Align the business steering system with how the CEO actually leads—and what they’re willing to change.

Improve the system for making decisions so people can make effective choices—instead of expecting great performance from those trapped in a broken one.

Make it explicit what decisions are being made, what assumptions they’re based on, and what’s expected to happen as a result.

Align the impacts of stakeholders’ decisions—to each other and to the whole—in advance, instead of afterward.

Hold people accountable for the quality of their decisions—what they do, the assumptions they base them on, and how they shape the company’s future.

6. Incentivize Desired Behaviors

Incentivize the behaviors and accountabilities that lead to better decisions.

7. Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit

Make the risks and probabilities the company is already taking explicit—to make better decisions under uncertainty.

Set targets that reflect meaningful ends—instead of meaningless numbers that become the ends in themselves.

Continuously improve the decision logic—not just the numbers they produce.

Improve the company’s chances of creating its desired future by improving the odds of its decisions.

Main Solution: Effective Ways to Create the Desired Future

Run the company like a living organism that improves its odds of reaching a meaningful future by learning and evolving—rather than running it like the Soviet Union, trapped by arbitrary, siloed quotas to follow a plan not worth executing.

To understand that fully, we’ll look at each sub-solution in more detail.

1. Match Leadership with the System

Align the business steering system with how the CEO actually leads—and what they’re willing to change.

The CEO and the system both exist to drive the best possible decisions for the company as a whole. When they’re misaligned, one becomes the bottleneck—and only the CEO can fix it.

That alignment—or misalignment—will happen either way. But it’s faster and cheaper to make it explicit upfront than to find out years later that the system changes never had a chance under the way the CEO actually wants to lead.

All meaningful business outcomes—like actual sales—come from the full set of decisions across the system, not from any one part like Sales, Supply, or Finance.

In other words:

- How decisions are made = system ∩ how the CEO leads

- Business outcomes = system ∩ how the CEO leads

A system built on truth can’t survive if the CEO rewards hitting a number more than exposing reality. If she wants forecasts that reflect reality, she must reward truth-telling—and tolerate uncertainty, even when it’s uncomfortable.

Changing the system means changing how decisions are made: people, structure, incentives, accountabilities. That means removing distorted incentives for false precision, punishing sandbagging, and redefining success.

It also requires the CEO to lead the change. If she wants a forward-looking, assumption-driven system, she must stop delegating system design to functions that can’t span trade-offs, change incentives, or resolve cross-functional conflicts.

Is she willing to reassign strong performers who thrived under the old system? Replace or retrain leaders who can’t operate in a probabilistic world? Dismantle structures that optimize the parts at the expense of the whole?

She must also weigh system change against every other business priority. These shifts compete for time, money, and attention. And because they alter power, they’re political—not just logical.

What matters most: fixing how decisions are made, hitting the budget this year, pushing through a major acquisition, or updating the ERP system?

The system must solve the CEO’s problems—not Sales’, Supply’s, or Finance’s. That requires clarity: what is she optimizing for? Growth? Predictability? Short-term? Long-term?

Once that’s clear, the system can be designed to reflect it.

If stability matters more than stretch, trade-offs should be resolved in favor of certainty. If long-term value matters more than this quarter’s plan, the system must free teams to take risk—without being punished when it doesn’t pay off.

But none of this will work if the CEO keeps legacy mechanisms in place.

You can’t build forward-looking accountability for decision quality while still steering by annual budget variances, backward-looking reviews, and static short-term financial targets.

New mechanisms must replace the old. That often means phasing out rigid plan creation processes like annual strategic planning and annual budgeting—not overnight, but deliberately.

One of the most common failure modes is layering new practices on top of old ones—creating noise instead of change. A rolling forecast built on top of a fixed budget will still bias behavior toward the budget.

The mechanics change. The behavior doesn’t.

Neither does decision-making.

A better system must also give the CEO a formal way to approve trade-offs and define risk appetite in advance. These decisions affect the whole—no single function can own them.

If Sales plans to hire and Supply plans to downsize based on different demand assumptions, the solution isn’t to force agreement or punish the one who guessed wrong.

It’s to give the CEO a mechanism to understand the risk—and make the call. Missed sales or tied-up capital? What’s the company willing to accept?

That doesn’t remove accountability. Sales, Supply, and Finance remain accountable—for their own decisions. But cross-functional trade-offs must be owned at the top.

The CEO must define what kind of system she wants:

- Performance or stability?

- Managing forward or backward?

- Short-term optimization or long-term value?

- Reality-based forecasts or ones that can be gamed?

- Risk-taking encouraged or punished?

- Incentives to optimize the whole or just their part?

- Decision-making as a priority—or an afterthought?

But none of those choices can conflict with how she actually leads. If they do, she must change how she leads, change the requirements—or prepare to be disappointed.

Leadership defines the system’s limits. If the CEO doesn’t own how the system works, no one else can.

And if she won’t lead the change, the system won’t change.

2. Redesign the System

Improve the system for making decisions so people can make effective choices—instead of expecting great performance from those trapped in a broken one.

Most performance issues aren’t personal. They’re systemic.

As Deming put it: “94% belongs to the system (responsibility of management); 6% special.”

In his terms, the vast majority of variation in results comes from the system itself, while the rest comes from rare, assignable causes—some human, many not.

In other words, the most effective way to improve performance is to change the system that management owns.

Ackoff made the same point: improving parts in isolation doesn’t improve the whole.

“If we have a system of improvement that is directed at improving the parts taken separately, you can be absolutely sure the performance of the whole will not be improved.”

So when executives call for “better execution,” they’re more focused on the 6% than the 94%.

And when they launch fixes in just one part—a new tool, process, or initiative—they guarantee no meaningful system outcome, like actual sales, will change.

Better question: Where’s the bottleneck this time? Where’s Waldo? It’s not about which technical tools are “right.” It’s about what behaviors the system produces.

As Meadows said: “The system, to a large extent, causes its own behavior.”

So when forecasts are sandbagged, exaggerated, or disconnected from reality, the odds are it’s not because people are incompetent or malicious. It’s because the system makes that behavior rational.

You don’t change behavior by upgrading isolated pieces.

You change it by changing the system that shapes how people decide—what they’re accountable for, how they’re incentivized, the targets they chase, and how they learn from reality.

The point isn’t how to improve each part. It’s what’s constraining the whole.

That’s also why every solution must fit the rest of the system. Even a technically perfect fix—like an AI tool that improves forecast accuracy—can be counterproductive if the system rewards hiding the truth.

So the real question isn’t “Is this solution good?” It’s “Does it fit with the rest of the system?”

Don’t ask, “How can AI make our forecasts more accurate?”

Ask, “What in the system makes people afraid to say what they really expect?”

If the goal is truthful forecasts—but the behavior is exaggeration—the bottleneck might be fixed annual targets set a year in advance. If that’s the case, no amount of AI will make forecasts more truthful.

Focus where performance is stuck—not where activity is happening. The constraint defines what limits the system today. Everything else is noise.

For example:

- Finance is working on rolling forecasting.

- Supply is developing S&OP.

- Sales is rolling out a new sales process.

- Product is implementing OKRs.

- HR is redesigning targets.

- The CEO is launching her “real strategy.”

All well-meaning—none guaranteed to matter.

This is doorknob polishing. It keeps people busy but doesn’t move performance.

That’s why the CEO must be the active owner of system change—accountable for how it works and evolves, and responsible for setting the goal, communicating the need, prioritizing resources, and changing how she leads.

She must act as the conductor—keeping focus on the real constraint.

Left alone, functions will always optimize themselves, not the system.

System change isn’t a big-bang transformation. It’s incremental.

Don’t start by rewriting all targets, killing annual budgeting, and rolling out probabilistic planning tools.

That’s like going from couch snacks to two-hour workouts every day. It won’t stick.

Start small—right at the constraint. No new tools. Just change the conversation. Instead of saying demand is 100, say there’s a 100% chance demand is 100. That one shift kicks off probabilistic thinking.

Like getting in shape: start with a 15-minute walk, not a triathlon.

The key isn’t how much you could change, or how fast—it’s staying focused on the bottleneck and making the change stick in the long term.

The first bottleneck is usually that decisions—and their impacts—stay hidden.

3. Make Decisions Visible

Make it explicit what decisions are being made, what assumptions they’re based on, and what’s expected to happen as a result.

The only way to influence the future is to make decisions.

And all decisions are:

- based on assumptions about the future (since there’s no data about it)

- expected to have some impact on that future (based on some forecasts)

Making both the decisions and their logic—assumptions and expected impacts—explicit allows them to be challenged, debated, and improved before they happen. It also enables effective testing and revising them afterward. In other words, it is prerequisite for effective learning.

This isn’t about predicting outcomes, locking anything in, or defining the right level of detail. It’s about clarity on what’s already happening—even if it’s informal.

Example: We’re going to acquire new accounts (decision) to increase sales (expected impact) because the market is flat (assumption).

Visibility doesn’t require a specific format.

Ackoff:

Because:

- “The more participative planning is, the less need to inform people afterward.”

- “When planning is continuous, documents tend to be obsolete before they’re finished.”

What matters is clarity: what decisions we’re making, what they’re based on, and what we expect them to do.

What matters most is exposing the logic—especially how decisions fit together—not obsessing over numbers.

Ackoff again:

If the logic behind decisions isn’t visible—what they’re based on, how they connect, and what’s expected—then people can’t effectively improve them, align with them, or be held accountable for them.

The biggest mistake is treating expected outcomes as certain, precise promises—rather than conditional outcomes of specific assumptions and decisions.

You can’t control outcomes. But you can improve them—by making better decisions. And you can make better decisions by better understanding the assumptions behind them and how those decisions fit together.

That’s why Amazon focuses on input metrics—because they reflect controllable decisions—rather than output metrics, which are more dependent on external factors and dumb luck.

Strategy thinkers often describe strategy as an integrated set of decisions—because focus and fit matter. That logic applies to all decision-making: some decisions work better together than others.

The same goes for the assumptions behind them.

Roger Martin:

You don’t need perfect predictions. But you do need to be clear about what you’re betting on.

Rita McGrath:

Too often, assumptions are either not understood or get treated as facts—until they don’t hold. And by the time anyone notices, it’s usually too late.

These aren’t just lessons for strategy. They’re fundamentals of effective decision-making at every level. So don’t ask, “Should we raise prices 5%?”

Ask, “Should we raise prices 5% and hire 100 reps—and what would have to be true for that to be a good combination?”

To manage performance forward, you need to know what decisions the expected outcomes reflect. To manage it backward, you need to know what was expected—and why.

If that logic isn’t visible, it’s harder to improve decisions. It’s harder to learn from outcomes. It’s harder to hold anyone accountable. And it’s harder to tell whether the decision was bad—or just unlucky.

That’s why the focus must be on assumptions, not numbers. Expected outcomes are just predictions of what happens if certain decisions are made and certain assumptions hold.

Before decisions are made, assumptions must be debated.

Ask: “What would have to be true for this to be a good decision?”

Then: “What would have to be true for this to be a good set of decisions?”

If you’re making a few decisions alone, you can do that in your head.

But when hundreds of people are making thousands of decisions—each based on different assumptions, incentives, and interpretations—it’s difficult to align them without being explicit about what they are.

4. Align the Decisions

Align the impacts of stakeholders’ decisions—to each other and to the whole—in advance, instead of afterward.

A company is a system. Sales, Supply, and Finance decisions have no standalone value—only in how they fit together.

Sales hiring 100 reps and entering new markets doesn’t grow revenue unless Supply has made decisions capable of serving that demand. Finance cutting $10 million doesn’t save money unless Sales and Supply have made decisions to reduce cost.

The question isn’t how good each stakeholder’s decisions are—it’s how well their decisions fit together.

That reconciliation happens anyway. Either you align decisions in advance—when you can still change them—or afterward—when all that’s left is blame.

Most alignment failures come from chasing the “right” number—rather than understanding which decisions are being made, and what risks they carry.

Sales may assume demand is 120, while Supply plans for 100. That’s not necessarily misalignment—if the decision impacts and risk tradeoffs are understood (see Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit).

Sales can grow demand in multiple ways, each with different timelines and supply implications:

- New orders need SKU-level inventory now.

- New accounts need added capacity in weeks or months.

- New markets need new capabilities over months or years.

If Sales’ demand decisions don’t align with Supply’s decisions on capability, inventory, or responsiveness, actual sales will fall short—regardless of how well each function executed.

Cue the usual excuses: “Sales’ forecast was wrong.” “Supply was inflexible.”

But much of that misalignment is avoidable.

Alignment doesn’t mean agreeing on a number—there is no “right” one (See Hidden Uncertainty and Risks).

It means aligning how decisions fit together—which decisions are being made, the constraints they face, and the relevant level of detail. The benefits come from one aligned set of decisions, not from one set of numbers.

Sometimes it’s about information—does Sales know something Supply doesn’t (e.g., large accounts, product launches)? That’s the usual fix: “improve the forecast.”

But the better lever is often this: change the decisions.

Sales could shift to pre-orders or give different types of discounts to customers. Supply could build inventory. Or accept higher costs for flexibility—shorter runs, more changeovers, faster response.

For example, a company might struggle to serve customers who place small, frequent orders the company can’t forecast. The obvious fix is to improve the forecast.

Another option is to hold more inventory or run shorter production series. But an even better move might be to change delivery terms—offering discounts for early orders or charging extra for small ones.

The point isn’t to prescribe the right choice or what’s feasible. In every company, in every situation, there are options—and performance depends on how well they fit.

There’s no right set of decisions hidden behind a “right” number. Just as there’s no perfect number, there’s no perfect fit—but you can make better decisions that fit better together.

Focusing on numbers risks losing sight of the decisions. Worse, numbers often become promises—driving bad decisions made to hit meaningless predictions instead of good ones made to improve performance.

The solution is to align decisions at the same level—for example, those that steer execution—because they’re interdependent. A production issue might not be solved in Supply, but in how Sales incentives are designed.

Example from Ackoff, Creating the Corporate Future:

Production output dropped due to excessive changeovers. It would have taken perfect forecast accuracy to match the impact of cutting just 4% of the most unprofitable SKUs.

Marketing resisted—those SKUs were often bundled with high-margin ones.

The solution: shift Sales’ commission from revenue to profit. Reps stopped pushing low-margin items and sold more profitable ones. Result: simpler mix, higher output, higher profits—without improving forecast accuracy.

Ackoff: “To have treated this problem as a production problem would have been to commit a white-collar crime.”

Treating it as a forecasting problem would’ve been no better.

Most companies need at least three alignment mechanisms—one for:

- the biggest decisions that steer the whole: where to play, how to win, what capabilities to build

- aggregate resource decisions: budgets, capacities, headcount

- decisions that steer execution: what to produce, which customers to visit

These mechanisms must also align vertically.

A strategy to compete in premium markets and win on service requires resource decisions that support it—like how much money to allocate to Sales and Supply—and decisions that steer execution that deliver it—like which customers to visit and which SKUs to produce.

To steer the company, alignment must happen across all levels, in advance. And whoever owns the whole—the CEO—must have a role in that mechanism.

The CEO’s job isn’t to pick sides between Sales and Supply, or to second guess their numbers—it’s to ensure their decisions align, and choosing the risk appetite for the whole.

That requires surfacing and aligning decisions early—not reviewing the fallout afterward.

If their decisions don’t fit, she can’t do her job. And if no one is aligning decisions across the system, no one is steering the whole. Trying to steer the whole by managing the parts can’t, by definition, deliver the best possible performance.

The payoff: better decision fit improves performance—even under uncertainty, even without perfect forecasts.

That only happens when people are held accountable for their decisions.

5. Own the Decisions

Hold people accountable for the quality of their decisions—what they do, the assumptions they base them on, and how they shape the company’s future.

Making decisions—and improving them—is the job. Both are possible under any level of uncertainty.

Each stakeholder—Sales, Supply, Finance—must be accountable for their own logic, not for precisely predicting the future or controlling the outcomes.

Take Sales. If they raise prices 5% and hire 100 reps, they must also own the assumptions those decisions rest on—e.g., the market will grow 10%, competitors will follow, and unconstrained demand will be 100.

That doesn’t mean the market has to grow 10%, or that 100 becomes a target.

It means:

- Assumptions were reasonable at the time

- Forecasts show no systematic bias over time

- Deviations trigger learning (see: Double-Loop Learning)

Decisions must be judged based on what was known when they were made—not in hindsight. That’s why decision logic must be visible upfront (see: Make Decisions Visible).

Accountability applies to your own decisions, assumptions, and expected outcomes—not to results or choices made by others.

Take Supply. Their decisions only create value when aligned with Sales and Finance.

Supply’s decisions should be judged against the forecast provided by Sales (e.g., demand = 100) and the constraints set by Finance (e.g., inventory cap = 20). Those inputs are not theirs to change. Their job is to make the best possible decisions given those inputs.

So even if actual demand turns out to be 120, their choice to hire 100 people and not expand capacity was logical—if they were told demand would be 100.

The quality of those assumptions is on Sales and Finance—not Supply.

A common challenge: how do you hold people accountable for decisions based on deterministic assumptions like “demand = 100” in a probabilistic world?

That’s why you also have to Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit, and subject them to continuous testing and learning.

And accountability doesn’t stop with functions—it includes the CEO.

She owns the cross-functional trade-offs—growth vs. working capital, upside vs. downside—and must be accountable for the company’s risk appetite.

If Sales expects demand to be 100 but sees upside to 120, and the CEO wants to prepare for 120, she owns that decision. If the company overstocks, that’s not on Sales or Supply. That’s on her.

If this feels hard to imagine in your company, that’s normal and expected—it probably wouldn’t work in the system you have now.

Holding people accountable for decisions—not shared outcomes—requires redesigning the system. That’s why this won’t fully make sense until you’ve seen how all the pieces work together.

But once they do, the payoff is real:

You shift focus from outcomes (uncontrollable) to decisions (controllable). You enable learning. You connect what people decide to what actually happens. And you strip out politics—replacing blame and gaming with one shared goal: make better decisions.

And because decision logic is visible, you can hold people accountable for the full impact of their choices—short-term and long-term—across the whole business (see Set Meaningful Targets).

But for it to work, the incentives must support it.

6. Incentivize Desired Behaviors

Incentivize the behaviors and accountabilities that lead to better decisions.

As Ackoff wrote in Creating the Corporate Future:

“Many of the deficiencies in the behavior of a system or its parts derive from incentives or disincentives that currently are in force even though they are not intended to have such consequences.”

“When behavior falls short, ask: What’s incentivizing it?”

Sales exaggerates forecasts not out of malice or incompetence—but because they’re incentivized to hit the budget and penalized for telling the truth. The problem isn’t intent. It’s the system.

Want truthful forecasts? Incentivize truth-telling.

Examples:

- Tie bonuses to forecast bias.

- Make it safe to tell the truth.

If Sales hits a target of 100, but their forecasts were consistently 30% too high, they might only earn 70% of the bonus. Full bonus = what was hit and how.

A biased forecast means weak influence or poor insight. Either way, the result came from luck or someone else’s decisions. They shouldn’t get full credit for what they didn’t drive.

Research is clear: rewarding outcomes distorts behavior, fuels gaming, and weakens long-term performance. Rewarding decision quality, assumptions, and process strengthens accountability—and improves decisions.

The fix isn’t more pressure for better outcomes. It’s better incentives for better decisions.

Counterintuitive—but it works: If you want better outcomes, stop fixating on outcomes. Incentivize better decisions, and better outcomes follow.

That starts with better questions. Don’t ask Sales to “hit the number.” Ask: What’s the forecast based on? What changed? What risks and opportunities exist?

If executives want to escape short-termism, they have to stop incentivizing it.

Stop approving year-end discounts that pull demand into Q4. Stop slashing R&D to protect this year’s EBIT. Don’t reward decisions that hit this year’s number at the expense of next year’s market share.

Incentives must match the time horizon of the decisions they aim to improve.

As Ackoff also noted:

“An effective incentive system should reward those who behave desirably no matter what others do.”

That means Supply shouldn’t be judged against a flat 98% service level. It should flex with demand—98% if demand is 100, 95% if it’s 120.

Supply operates on the forecast Sales confirms. Judging them on actuals means blaming them for decisions they didn’t make—based on information they didn’t have in time to act.

In other words, it holds Supply—who has no influence over demand—accountable for it, while letting Sales—who does—avoid accountability.

That makes no sense.

It flips the focus. Instead of making better supply decisions (their accountability), they waste time trying to “fix” the demand forecast (Sales’ accountability).

Best case, it wastes time and resources. Worst case, Sales and Supply’s decisions misalign—and the company performs poorly, no matter how well it “executes.”

Each function must be accountable for the decisions they influence:

- Sales for demand

- Supply for supply against that demand

When both are held to what they influence, the whole improves. Sales is incentivized to forecast demand truthfully. Supply is incentivized to plan supply accordingly. The loop tightens—and the system learns.

Over time, bias drops, assumptions improve, and decisions get better.

You get what you incentivize. Incentivize outcomes, and people will game the numbers. Incentivize decisions, and people will improve the business.

To do that effectively, you also need to make uncertainty visible.

7. Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit

Make the risks and probabilities the company is already taking explicit—to make better decisions under uncertainty.

That includes assumptions, expected outcomes, and the decisions themselves.

Instead of saying demand will be 100—because of decisions to raise prices 5% and hire 100 reps, based on assumptions like 10% market growth—say there’s a 50% chance demand exceeds 100, based on:

- 80% chance prices increase 5%

- 95% chance 100 reps are hired

- 50% chance market grows 10%

You don’t need to say all of that every time—but you should be able to.

Deterministic numbers make things more complex and less grounded in reality.

Take Jeff Bezos’ example:

“Given a ten percent chance of a 100× payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten.”

How do you describe what you think will happen?

- Probabilistically: 10% chance of making $100M

- Deterministically (pick one):

- Most likely = $0

- P50 = $0

- Expected value = $10M (but never actually happens)

- Upside = $100M (only 1 in 10 cases)

Each deterministic view tells part of the story. None tell the full story. You’d need multiple scenarios to approximate what a single probability already captures. More complexity, worse fit.

That’s the problem.

The benefit of probabilities isn’t accuracy or precision—it’s fidelity.

They better reflect how decision outcomes actually behave—and tell the full story of what to expect. They also clarify tradeoffs, because the underlying risks are clearer, which enables more effective decision alignment.

For example: Supply hires 100 factory workers for $5M to avoid a $10M profit loss—based on demand of 100.

Whether that pays off depends on the probability that demand exceeds 100—when all workers are needed—or drops below 90—when none are.

In other words, whether the demand of 100 is a P80 or a P20:

P80:

- 80% chance demand exceeds 100, 10% chance it stays below 90

- 80% chance to gain $10M, 10% chance to lose $5M

- Expected value: +$8M

P20:

- 20% chance demand exceeds 100, 70% chance it stays below 90

- 20% chance to gain $10M, 70% chance to lose $5M

- Expected value: –$1M

Same decision. Same cost. Different risk. Different payoff.

With probabilities, alignment shifts from debating a “right” number that doesn’t exist to focusing on what matters—what decisions to make, what risks and tradeoffs they involve, and how to improve the odds of winning.

They also sharpen accountability for decision quality.

Hiring 100 workers can be a good decision even if demand ends up at 90 and the company loses $5 million—or a bad one even if demand hits 100 and profits are up $10 million. (More in Use Double-Loop Learning.)

So instead of holding Supply accountable for the $5 million loss—which they didn’t control—or basing the decision on demand being exactly 100 (which has a 0% chance), you hold them accountable for the quality of the logic: how well the risks, tradeoffs, and odds were understood at the time.

That includes the CEO. She might still choose the P20 scenario—with a 20% chance to gain $10M and an expected $1M loss—if it improves the odds of entering a new market or avoids damaging customer goodwill, both of which could yield far greater returns over the long term (See Improve the Odds to Win).

Supply shouldn’t be held accountable for the $5 million cost—or for the decision logic. It wasn’t their call. It was the CEO’s.

Probabilities enable better incentives. You can’t effectively incentivize truth-telling in a probabilistic world with deterministic tools.

Instead of pushing Sales to hit a 50/50 forecast by tracking bias—as in Incentivize Desired Behaviors—probabilities let you evaluate the full prediction set: decisions, assumptions, and outcomes (see Use Double-Loop Learning).

They also make it possible to take high-risk, high-reward bets—like Bezos’ example, and make targets more meaningful.

Say the original target was 100, based on 5% market growth. If growth is now flat, that same target might be a P20, not a P50.

Targets can stay the same, but evaluation changes: a P50 should land half the time; a P20, only one in five.

The same logic strengthens learning and keeps incentives focused on improving decision quality—not just chasing numbers.

Probabilities don’t make you more accurate or precise. They reveal what was hidden—the odds behind the decisions, and how they changed.

The earlier P80 vs. P20 example was exaggerated for effect. In practice, the gaps are often smaller—but the stakes are just as real.

Most decisions aren’t between right and wrong, or profit and loss—they’re between two valid options:

- P60: 60% chance to gain $10M, 20% chance to lose $5M → EV = +$5M

- P40: 40% chance to gain $10M, 40% chance to lose $5M → EV = +$2M

If you can’t tell the difference between a 60/40 and a 40/60, you’re not just making weaker calls—you’re leaving millions on the table.

The natural reaction: “Sounds good in theory, but not in practice.”

It’s not theory. It’s just unfamiliar.

As Tetlock said:

“Foresight isn’t a mysterious gift bestowed at birth. It is the product of particular ways of thinking, of gathering information, of updating beliefs. These habits of thought can be learned by any intelligent, thoughtful, determined person.”

So if you think it won’t work—you’re right.

And if you think it can—you’re also right.

This reshapes every part of making better decisions:

As Charlie Munger put it, not using probabilities is like being a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest. But they’re ineffective if the targets you aim for are flawed.

8. Set Meaningful Targets

Set targets that reflect meaningful ends—instead of meaningless numbers that become the ends in themselves.

Ackoff:

You can sell anything to hit $1 billion. But if the aspiration is to lead the wellness sleep market, you need to grow wellness sales—for example by acquiring new customers or increasing preorders.

Meaningful targets define the future you want to create.

Example:

- Short-term: 50% of revenue from wellness

- Mid-term: Move from #3 to #2 in wellness

- Long-term: Become market leader in wellness

If hitting those targets hurts total sales, ask: should wellness leadership be the goal? If the results disappoint, maybe the aspiration was wrong.

Targets must match the impact horizon of decisions. If today’s choices shape outcomes 2–5 years out, set those targets now—because something will steer them anyway.

If you steer only to short-term targets, you’ll also bias results to the short term.

Decision horizons differ by role—so should targets:

- Top Management: multi-horizon targets that shape long-term outcomes

- Execution: short-term targets tied to immediate actions

For example, top management deciding to enter the wellness sleep market—assuming demand will grow and brand leadership will drive share—should have targets extending over several years.

While a person assembling the products should have targets that may only extend to the end of the shift.

This enables holding people accountable for the full impact of their decisions—across the whole business, short-term and long-term.

Cascade by decision logic—not numbers. Don’t divide $1B into $300M for the U.S. and $200M for Europe. Instead: define what moving from #3 to #2 globally requires. Maybe the U.S. needs to reach #3.

That logic drives (for instance):

- U.S. target: 20% of sales from new wellness customers

- Execution target: 70% of preorders focused on wellness products

These targets create focus and fit—because they’re tied to who the company wants to become.

They turn the company into a business logic testing machine. Missing a target doesn’t necessarily mean execution failed—it may mean the logic behind the decisions, including targets, requires improvement.

You can’t judge decision quality by whether $1 billion was hit. But when targets cascade from who the company wants to become, they enable testing and refining of the business logic.

Like any decision, targets are valid only under specific assumptions—and should be revised as soon as those assumptions become obsolete (see: Use Double-Loop Learning).

This shifts the company’s focus from chasing meaningless outcomes to shaping the decisions that create meaningful ones. That doesn’t weaken performance—it strengthens it.

Focus on logic—and the numbers improve too. Not just because the logic is better, but because it removes the incentive and the ability to game the outcomes.

But to drive learning, targets must reflect probability—and be grounded in assumptions. (See: Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit.)

Example:

We have a P50 target to reach #2 in wellness in 12–24 months, assuming:

- No major breakthroughs by competitors (P70)

- No significant new regulations (P50)

- No major new market entries (P30)

Explicit probabilities make targets both more realistic and more ambitious. Most get this backwards, thinking that clinging to a static target like “$1 billion—no matter what shows “high standards,” and “focus in execution.”

It doesn’t.

If your P50 assumed no legislative restrictions and restrictions hit, it’s now a P30. If P30 was the intended difficulty, set it that way from the start. Probabilities stabilize the intended difficulty.

The reverse is also true: if restrictions ease, your P50 becomes P90, and you can “hit the target” even with bad calls. That’s not high standards—that’s roulette.

Static targets reward luck and punish great decisions. Probabilistic targets account for luck and reward great decisions.

But for that to work, you also need effective learning.

9. Use Double-Loop Learning

Continuously improve the decision logic—not just the numbers they produce.

Don’t ask, “How can we hit 100?”

Ask, “Why do we believe we should hit 100?”

Don’t ask, “How can we improve execution?”

Ask, “Why do we believe the plan is worth executing?”

| Trigger Event | Traditional Response | Double-Loop Response |

| Q2 misses forecast | “Push harder in Q3.” | “Which assumptions failed?” |

| Forecast hits | “Great execution.” | “Did we just get lucky?” |

| Team blames luck | “Nothing we could do.” | “Did we misjudge the odds?” |

This shifts focus from chasing outcomes to improving decisions. It avoids Type III errors: solving the wrong problem.

If the forecast was 100 and actuals were 90—based on 5% price increases and 10% market growth—ask:

- What actually happened to prices and market growth?

- How did that impact demand?

- What does that mean for future assumptions?

Update the logic, not just the number. And do it whether the forecast was missed, hit, or exceeded—because performance depends on decision quality, not whether you guessed right.

For example—using the Supply hiring 100 workers case from Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit—it could still be a good decision even if demand stayed at 90, none were needed, and the company lost $5 million. If, at the time, it was reasonable to expect 10% market growth, then Covid-19 killing that growth means the loss came from bad luck, not bad decisions.

The reverse is also true. The same decision could make $10 million and still be bad if there was no reason to expect 10% growth—yet Covid-19 unexpectedly boosted demand. In both cases, the outcome was luck, not decision quality.

Double-loop learning is what makes all the other solutions effective:

- Reveals decision impacts (Make Decisions Visible)

- Enables cross-functional alignment (Align the Decisions)

- Enables accountability (Own the Decisions)

- Incentivizes truth-telling (Incentivize Desired Behaviors)

- Enables effective decisions under uncertainty (Make Probabilities and Risks Explicit)

- Focuses effort on what matters (Set Meaningful Targets)

The main reason why most companies fail to learn is because they think already “know the right answer.”

“We already have a plan—we need to focus on execution.”

That’s why common planning processes—like Annual Budgeting or so-called “Strategic Planning”—fail to drive performance: they don’t even have a mechanism for learning, let alone an effective one. They are a poor fit to a probabilistic, ever-changing world.

They’re focused on “creating a plan” or “hitting the number.”

A plan is just a coordinated set of decisions based on assumptions—assumptions that over time will become obsolete in a probabilistic world.

Without double-loop learning to question and adapt those decisions, companies lock themselves into outdated logic. Focusing only on “execution” is like running in a straightjacket—voluntarily limiting their ability to shape the future.

For learning to be effective, the alignment mechanism (i.e., the planning process) must be continuous. Its cadence—weekly, monthly, quarterly—should match the nature of the decisions.

As Russell Ackoff put it:

“Planning should be a continuous process and hence no plan is ever final; it is always subject to revision. A plan therefore is not the final product of the planning process; it is an interim report.”

A useful rule of thumb (not literal): revise the logic at a cadence at least 10–20× more often than the typical decision lifecycle.

- Multi-year resource decisions: revise monthly or quarterly—not annually

- Short-term operational decisions: revise weekly or daily—not monthly

Learning must also span decisions—both horizontally and vertically:

- Across similar-level decisions (e.g., budgets, capacities, headcount)

- Across different levels (e.g., strategy shaping resource logic; resource choices shaping the operational logic that guides execution)

The goal isn’t to get individual decisions “right”—it’s to improve the company’s overall decision logic.

Strategic:

- How sound is the logic behind strategic decisions?

- How well does it align with the logic behind tactical decisions?

Tactical:

- How sound is the logic behind tactical decisions?

- How well does it align with strategic and operational decision logic?

Operational:

- How sound is the logic behind operational decisions?

- How well does it align with tactical decision logic and execution?

The problem isn’t that companies do this badly—it’s that they don’t do it at all in advance. They only do it in the rear-view mirror—while blaming each other.

For those companies, the fix isn’t to refine the current approach. It can’t work, even in theory. They need different tools and a different mindset—shifting from single-loop to double-loop learning.

Learning has to go beyond single outcomes—beyond one week, one decision, or one assumption.

- Look for patterns over time:

- Did the key assumptions hold over 4–6 or 12–24 months?

Did the odds hold—not just the outcomes? (Were our “70%” calls happening about 70% of the time across comparable cases?)

For example:

- Don’t just ask: “Did 10% market growth happen?”

- Do ask: “Did our 70% probability for 10% growth hold?”

And check the assumption stack, not just a single line item:

- 70% chance for 10% market growth

- 50% chance competitors follow price increase

- 90% chance for 5% price increase

Judge whether the probabilities—not just the outcomes—held over time. If your 70% calls hit much less (or more) often, your beliefs are miscalibrated. The fix is to adjust the P-levels, not just the narrative.

This is where Brier scores become useful—they can be used to evaluate the quality of the full decision logic, not isolated results.

The shift is:

- From outcomes you don’t control → to decisions you do control

- From individual decisions that don’t matter → to overall decision logic that drives performance

- From overall decision logic as an abstraction → to the decision-makers who shape it

In other words, it shifts the focus from meaningless outcomes and vague assumptions to the person behind the decisions—because performance ultimately depends on how good they are as decision-makers.

It also counters the common excuse for avoiding probabilities: “We don’t have enough data.”

That may be true for a single outcome, but not for patterns across decisions or for tracking how well decision-makers calibrate over time. Within weeks or months, you can evaluate dozens or hundreds of predictions.

What matters isn’t whether one assumption was right, but whether the decision logic is improving—because performance comes from improving the logic behind decisions, in other words, from improving the odds to win.

10. Improve the Odds to Win

Improve the company’s chances of creating its desired future by improving the odds of its decisions.

Don’t manage to whether siloed targets are hit or every decision has a positive outcome. Instead, ask: Which decision—or group—is the bottleneck to improving overall expected performance?

Not whether:

- Sales hits 100

- Supply holds inventory of 20

- Finance delivers EBIT of 10

Same logic as in Redesign the System—but applied to decision-making. That was about fixing the system’s bottleneck; this is about changing the bottleneck decisions within it.

The traditional approach slices the company into deterministic silos—by function, market, or time bucket—and assumes that hitting each silo’s target maximizes overall performance.

It doesn’t.

Treat the company as one decision-making machine, with all decisions combining into a single probability of achieving the desired future. Find the bottleneck decisions that most improve the odds for the whole.

Sometimes the bottleneck isn’t tactical or operational—it’s strategic. Decisions about where to play and how to win can limit the performance of the whole.

Example:

- Current strategy (play in traditional, win with price): 70% chance of $200M → EV = $140M

- New strategy (play in wellness, win with brand): 50% chance of $400M → EV = $200M

- Tactical tweaks (reallocate within traditional): 30% chance of $60M → EV = $20M

Takeaway: No amount of tactical choices can out-deliver a strategy with higher expected value.

Two wrong ways to understand the example:

- Treating it like an equation with a “right” answer

- Rejecting it because “you can’t know the numbers”

Both miss the point. This isn’t accounting or physics—it’s not about precision or certainty.

It’s about leverage. It’s about finding the crux—what Richard Rumelt describes as the single most critical part of the challenge.

In practice, that’s the current bottleneck to reaching the desired state. Find it (“Where’s Waldo”), align all effort there until it’s no longer the bottleneck, then move to the next.

Probabilities and expected values aren’t facts. They’re beliefs. And that’s the value: you’re not solving equations, you’re exposing assumptions you already rely on—so you can improve them.

All decisions rest on assumptions about probability and utility.

Expected value is just odds × utility.

You improve performance by improving one—or both.

The goal isn’t to find the right numbers. It’s to identify the decisions with the most power to shift expected value, at a risk level you can live with. That’s as much art as science. It’s about being roughly right, rather than precisely wrong.

Performance doesn’t depend on certainty. It depends on improving baseline judgment—which is always flawed. You don’t need the “right” numbers. You need a better understanding of the world.

To do that:

- Focus on the bottleneck

- Focus on the decision logic: the assumptions – not the numbers

- Look for decisions where the potential upside far outweighs the potential downsides

- Treat no decision as set in stone—not even strategy, budgets, or targets

- Continuously test and improve your logic (Use Double-Loop Learning)

Most companies do the opposite.

Most of their focus is on individual outcomes and “being right.” They try to improve everything at once—while locking down the biggest levers. They obsess over the numbers, while neglecting the assumptions behind them. They chase multiple targets, protect pet projects, and cling to bad bets because they’re labeled “strategic,” “in the budget,” or “stretch targets.”

Then they call that “managing performance,” “being focused on execution,” and having “high standards.”

But every decision—strategic or operational, target or not—is a hypothesis. It rests on assumptions and on outcomes you don’t control.

You might believe “playing in wellness” is the best move. But you don’t know. So you need to test it—just like any budget, forecast, or priority. Everything should be subject to revision—because everything should be subject to improvement.

And the goal is to raise expected value (odds x utility). Don’t ask, “How do we hit 100?” Ask, “How do we improve the expected value of 90?”

How? For example:

- Improve your understanding of decision odds (calibrate probabilities more realistically)

- Improve your understanding of the utility (clarify the payoff and its constraints)

- Change the decision (A vs. B — pick the one with higher expected value)

- Improve decision odds (e.g., change the team, resources etc.)

- Rebalance short- vs. long-term bets (adjust the portfolio of decisions to match desired risk/return)

The key is to try to increase the number of decisions where the potential upside is much bigger than the downside, even if the latter is far more likely.

You can train people to judge odds better. Or put your best decision-makers on the biggest bets. This already happens—just without logic, discipline, or ownership.

Good decisions get abandoned after one bad outcome. Bad ones get defended with data that reflects luck. Resources follow politics, habit, or power—not performance.

People are promoted for luck, or ability to game the system—not performance. Best people are working on their pet projects, not what improves company level bottlenecks.

To improve performance, improve the odds of the decisions that matter most. You can steer toward stability or lower risk—but only by accepting lower performance. As in Match Leadership to the System, risk appetite is ultimately the CEO’s call.

There are no right or wrong answers.

All the other solutions—visibility, alignment, accountability, incentives, explicit probabilities and risks, targets, learning—support it.

But in the end, only one thing drives performance: better decision odds. And that ultimately depends on how effectively the company creates the future it desires.

Main Solution: Effective Ways to Create the Desired Future

Run the company like a living organism that improves its odds of reaching a meaningful future by learning and evolving—rather than running it like the Soviet Union, trapped by arbitrary, siloed quotas to follow a plan not worth executing.

The difference: focus on decision odds, not fixed outcomes; the whole, not the parts; and learning, not the illusion of control. In other words, focus on real performance, not the illusion of performance.

| Instead of this | Do this |

| Try to “hit the number” | Improve the odds of decisions |

| Focus on the parts | Focus on the whole |

| Thinking you have the “right answers” | Focus on learning |

| Incentivize gaming the system | Incentivize good decisions |

| Trying to improve all decisions | Focus on improving bottleneck decisions |

| Focus on outcomes | Focus on decision logic |

| Arbitrary financial targets | Define what the company wants to become |

| Hold people accountable for outcomes | Hold people accountable for decisions |

| One set of numbers | One set of decisions |

| Placing blame afterward | Align decisions in advance |

| Hiding probabilities and risks | Make probabilities and risks explicit |

| Trying to execute in a broken system | Improve the system |

| System that conflicts with the CEO | System that aligns with how the CEO leads |

| Parts taking accountability for the whole | CEO takes accountability for the whole |

That means managing through the logic of decisions—not outcomes. Outcomes matter, but the most effective way to achieve them is to improve decision quality.

Traditional thinking steers decision toward deterministic siloed outcomes. That might work in a predictable world. In the real, probabilistic one, it isn’t effective.

That’s what Cassie Kozyrkov meant when she said evaluating decision quality by its outcomes is “one of society’s favorite forms of mass irrationality.”

It’s also why steering all decisions toward static, predetermined outcomes will hinder performance. Just ask the Soviet Union.

Your only lever is better decisions—built on stronger logic. Over time, that delivers better outcomes than chasing static outcomes, because chasing outcomes trades away decision quality to mask the natural variability of dumb luck.

Why this solution works

- The world is probabilistic—not deterministic.

- It’s impossible to precisely predict the future.

- The only way to influence the future is by making decisions.

- There are no right numbers or decisions—only different decision odds.

- All outcomes are the product of probability and utility.

- Decision quality and outcome quality are distinct.

- There is no data about the future—only assumptions.

- All decisions are based on assumptions and involve predictions.

- Decisions interact with each other and have different time horizons of impact.

- Impacts of interdependent decisions are always reconciled at execution.

- The performance of a system is determined by how its parts interact.

- People act to protect and advance their own perceived interests.

- People in companies always have accountability for something.

The shift is:

- From deterministic numbers → to probabilistic logic

- From siloed parts → to company-level interactions

- From uncontrollable outcomes → to decisions that influence the odds

- From gaming the system → to making better decisions

- From illusion of performance → to real performance

Practical effects:

- Improves decision quality – Focuses on sound logic, not gaming.

- Aligns the system – Ensures decisions work together.

- Targets bottlenecks – Concentrates effort where it matters most.

- Adapts continuously – Keeps decision logic in sync with reality.

- Delivers better outcomes – From higher-quality, aligned, focused, and adaptive decisions.

Why people resist—even when it works

The same traits that make this approach effective also make it unpopular.

Real performance is messy, unpredictable, and uncontrollable. You can do everything “right” and still get bad results. That’s psychologically unsettling. Most would rather cling to an illusion of control and trade performance gains for the comfort of predictable outcomes.

Gaming the system or suboptimizing a part often gives better odds of personal success—especially for mediocre or below-average performers, which is most people. Even high performers can’t be sure they’d stay on top under a new way of working. It’s a risk most would rather not take.

That’s why the number of people who actually prefer this approach over their current broken system is small—often zero.

People care about company results—but they care more about their own. A system that optimizes the whole will sacrifice some parts. From the company’s view, that’s good. From the individual’s, it’s bad. It’s not right or wrong—it’s perspective.

And while people say they want the truth, they often don’t.

They may say they want accurate forecasts, but they want even more to look like great performers—and to be able to game the forecasts in their favor, or hide the impacts of their decisions.

Supply says they would have performed well—if the forecast had been right. But they don’t necessarily want to expose how well that claim holds up. In fact, when the demand forecast is improved, it often reveals that Supply wasn’t that effective either.

The same dynamic plays out at the top. Executives say they want better execution, but they don’t necessarily want to confront the real reason the company isn’t growing: not poor execution, but poor strategic choices.

As A Few Good Men put it: “They can’t handle the truth.”

Same reason people lie even to those they love. When your spouse asks if they’ve gained weight, telling the truth isn’t the right move—even if they say they want to hear it.

Philip Tetlock proved that probabilistic forecasting works—and that people can quickly improve. But he doubted whether the same would work as well in companies.

His Superforecasters were picked for one thing: prediction skill. In business, other traits dominate. And few want their forecasting ability exposed.

Same with decision-making: even if measuring it improved performance, most wouldn’t want to know how they rank—especially if it showed they’re worse than their peers, let alone worse than somebody more junior or lower status.

Focusing on the system’s bottleneck might create the biggest gains for the company—but it also kills pet projects. These are often the things people enjoy, even if they don’t matter to performance.

Even the CEO isn’t exempt. Her personal incentives may not align with the company’s long-term interest. Her odds of career success may rise faster by chasing short-term wins than by optimizing long-term decisions.

These principles may maximize the odds for the company to succeed—but they often conflict with the best interests of individuals, their teams, and even the CEO.

Bottom line: Most reject this because it’s rational for them to reject it.

Quarter-end blame games don’t happen because people are incompetent. They happen because the dysfunction works—for them.

To the company, it’s a system and leadership failure.

To the people inside, it’s the system working as intended—letting them distort the truth and game the odds in their favor.

That’s why, for most, the status quo beats changing it.

Why it still matters

Every company exists to achieve something as a whole—which is exactly what this solution is built to deliver.

They may never fully follow it—because they have to balance the parts against the whole, while navigating human nature: more emotional, biased, and political than rational, objective, or truth-seeking.

Yet they can’t escape four fundamentals this solution aligns with:

- World – probabilistic, unpredictable

- Decisions – interdependent, time-bound, with varying odds

- People – driven by personal incentives

- Companies – systems with defined accountabilities

Personal interests often conflict with what’s best for the whole. But owners’ interests depend on what the company achieves as a whole—and they ultimately decide how it’s run. This solution serves those interests.

And despite bias, politics, and self-preservation, most people still want the company to succeed. That’s the purpose they attach to their role—even if they also have other interests. This solution delivers on that claim.

It fits reality. And it fits the reason companies—and the roles within them—exist.

That’s why it works.

Conclusion

To maximize the odds of creating the future you want, focus on decision quality—not outcomes.

Most companies do the opposite. Cassie Kozyrkov calls it “one of society’s favorite forms of mass irrationality.” She’s right.

If the forecast is 100 and actuals are 90, the wrong questions are “Who underperformed?” or “How do we close the gap?” The right ones are “What can we learn?” and “How can we improve the decisions—or the system behind them?”

In a probabilistic world, that’s all anyone can do.

Over time, it’s what drives outcomes. You can’t maximize the whole by optimizing the parts—yet companies keep trying. They launch initiatives to improve planning, forecasting, budgeting, incentives—but only in isolation.

As Ackoff pointed out, that’s why most improvement efforts fail.

That’s also why so many dismiss real decision principles—like probabilities—as “theoretical.” They try one piece, it fails, and they conclude the whole thing’s flawed.

All they’ve really proved is obvious: you can’t fix the whole by fixing the parts.

It’s like testing market pricing inside the Soviet Union, where Gosplan still dictates annual and five-year plans—then declaring that capitalism “doesn’t work in practice.”

When making decisions, companies double down—optimizing the outcomes of a subset of decisions to hit predetermined, meaningless targets—instead of improving the quality of all decisions across the company.

That’s a triple Type III error: optimizing the wrong thing (part of the decisions), against the wrong thing (meaningless outcomes), with the wrong thing (a system incapable of effectively shaping the future).

No wonder forecasts miss, end-of-quarter debates persist, and the blame game between Sales, Supply, and Finance is universal. It’s exactly what you’d expect from how most companies are run.

It’s a feature, not a bug.

Practical Insights

- Match leadership with the system; one is always the bottleneck.

- Redesign the system; don’t try to execute in a broken one.

- Make decision logic visible so it can be improved.

- Align decisions of different stakeholders in advance instead of afterward.

- Hold people accountable for the quality of their decisions.

- Incentivize desired behaviors that improve decision quality.

- Make probabilities and risks explicit to manage them effectively.

- Set meaningful targets that account for the time horizon of decision impacts.

- Use double-loop learning to continuously improve decision logic.

- Focus on improving the bottleneck decision odds to create the desired future.