Introduction

Executives struggling with a lack of long-term growth may blame the organization for ‘poor execution’ without realizing that not only are the plans they hold the organization accountable for not worth executing, but that holding the organization accountable for ‘hitting’ them may be the root cause of the lack of long-term growth.

Sure, poor execution may also play a part in poor results, but that varies case by case.

What’s practically certain is that in all cases where the focus is on ‘hitting the plan,’ the organization not only wastes time and effort on activities that don’t drive long-term growth but also actively hinders it.

The simple reason is that it is virtually impossible to describe what ‘good performance’ looks like in the dynamic, probabilistic real world through a static plan that is updated annually. Demanding adherence to the plan presents a Sophie’s Choice for managers: whether to ‘hit the plan’ or improve performance.

Common symptoms include (but are not limited to): ‘Venetian Blinds’ or ‘Hairy Backs,’ created by the ‘strategic’ or long-term plans, approving budgets where the topline is approved but costs are cut in half, as well as year-end gimmicks like cutting marketing costs or moving demand from January to December to ‘hit the plan.’

Focusing on static plans is not only what many companies do today, but it’s also how the Politburo managed the Soviet Union in the 1920s. Put differently, it’s ironic that while most executives are devoted proponents of free-market principles, how they run their companies resembles more communism than free-markets.

In reality, there is little evidence that these principles improve long-term performance. In fact, over 70 years of research shows that if ‘strategic planning’ were a medicine, in three out of four cases, it would either have no effect or make the condition worse.

Despite this, surveys of managers and executives show they overestimate its impact on financial metrics by a factor of at least three—and sometimes as much as six.

Creating annual and 5-year plans resembles more bloodletting than antibiotics. It was practiced for 2,000 years with ‘great results’ by the best physicians of their time. In reality, it killed more people than it helped.

Similarly, Soviet planning practices—and the corporate planning systems modeled after them—are far more likely to bleed companies to death than to drive their long-term performance.

Related (click to open): Practical Experience Can Be Misleading

People are capable of believing in things that not only fail to produce the desired result but the exact opposite of it.

For example, in the mid-1800s, bloodletting was considered a practical cure for infections. After all, it was practiced by the best physicians with ‘great results.’ It was practiced for 2,000 years, and despite good intentions, it ended up killing (allegedly) more people than it cured. It’s natural to think, that was back in the Middle Ages, when no one knew better. “Surely now, people have changed.”

While a single book today can contain more information about medicine than the best physicians in the 1800s could have learned in their entire lives, people, fundamentally, remain the same. They still believe in all kinds of things with little to no proof that they actually work, simply because ‘this is how we’ve always done it,’ or because ‘everybody does it.’

Similarly, the most common modern planning practices—such as the annual budgeting process or annual strategic planning—are, in the light of what is known today, more akin to bloodletting than antibiotics. They are, therefore, more likely to bleed the company to death than to help grow its profits in the long term.

Planning in the Soviet Union

Planning in the Soviet Union was based on annual and five-year plans created by the centralized planning committee, Gosplan.

The Five-Year Plans set broader strategic direction for the long term, while the Annual Plans served as tactical tools to break those goals into specific yearly targets and resource allocations.

For example, a five-year plan might set the key objective of increasing steel production from 4 million tons in Year 1 to 10 million tons by Year 5.

This objective would then be broken into annual quotas, such as:

- Year 1: 5 million tons

- Year 2: 6 million tons

- Year 3: 7 million tons

- Year 4: 8.5 million tons

- Year 5: 10 million tons

Gosplan allocated critical resources such as coal, iron ore, and labor to factories like the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works based on these annual targets.

Performance monitoring was a constant process, occurring monthly, quarterly, and annually. State-owned production units were required to submit detailed reports to regional planners, who aggregated the data and sent it to Gosplan for review.

For instance, a steel factory such as Magnitogorsk Iron might submit a monthly report stating it produced 500,000 tons of steel in February, slightly below its monthly target of 520,000 tons. This discrepancy would be flagged during the monthly review at the regional level.

A factory manager who exceeded the steel production quota might receive public praise, a medal, or additional resources. Conversely, a manager whose factory consistently underproduced could be arrested or sent to labor camp.

Strict control mechanisms to ‘hit the plan’ were effective in ensuring compliance with annual and five-year plans, but they also resulted in managers prioritizing ‘hitting the plan’ at any cost.

Planning in Many Companies Today

The planning practices of companies often resemble the following (not always, but many of these elements are also presented as best practices by finance experts):

- Create a five-year plan (e.g., for 2025 to 2029) outlining ‘strategic priorities.’ These plans are often referred to as a ‘strategy.’ However, it’s not uncommon for companies to have several such plans—one for each function or business unit.

- Develop an annual budget and annual operating plan (AOP) for the next calendar year (e.g., 2025). This is usually completed in H2, with final approval from the management team and the board by December.

- Set annual bonus targets based on the budget. For example, achieving revenue of $1 billion and a margin of $100 million.

- Create a forecast (latest view of the future) by including actuals and updating what has changed from the budget. This is typically done monthly.

- Conduct a variance analysis comparing the budget to the forecast and understand the key drivers (80/20) of delta.

- Plan gap closing actions to align the company’s performance (forecast) with the budget (target).

For example, a corporation with a five-year objective to grow annual revenue from $900 million to $1.4 billion might break this into annual targets:

- Year 1: $1.0 billion

- Year 2: $1.1 billion

- Year 3: $1.2 billion

- Year 4: $1.3 billion

- Year 5: $1.4 billion

Annual targets would then be further broken down during the annual budgeting process by the central finance team and allocated to different business units. This process often involves multiple rounds of adjustments, during which business units present their bottom-up plans to the management team.

However, if the company has an overall target to hit—whether set by the management team or the board—those numbers are likely allocated to business units regardless of whether they are based on solid real-world assumptions.

Adherence to the plan is often monitored at monthly intervals. While the main focus may be to hit the annual target, there is also intense pressure for each silo to ‘hit the plan’ on month level. Local finance teams track and report progress toward targets, which are then reviewed by the central finance team and company leadership.

The main focus is on the delta between the budget and actuals and what actions will be taken to correct the course.

Business units that are on track or exceeding the budget are praised, while those falling short are reprimanded and subjected to greater scrutiny. These units are required to implement gap-closing actions and provide more detailed explanations of their performance.

Planning in Soviet Union vs. in Many Companies Today

Imagine two people describing their current planning principles—one from the 1920s Soviet Union and one a finance expert from the 2020s—would you be able to tell which is which?

The similarities are striking.

For example:

- Purpose of planning: Both see the purpose of planning as creating a static plan, which is then followed at high costs, regardless of what happens in reality.

- Calendar based: As a corollary to the previous point, planning in the 1920s Soviet Union (and in finance best practices today) was a ‘calendar-based’ event, not a continuous process.

- Focus on numbers: Emphasis is on determining what are the key numbers that represent the desired (pre-determined) outcomes.

- Target setting: Both rely on setting fixed rigid targets, whose level of difficulty over time is largely dependent on luck.

- No mechanism to revise plans: Both are ‘unscientific,’ meaning that they lack a mechanism to test and revise hypothesis (how well the business logic described in the plans aligns with the reality).

- Time-horizon: Both use arbitrary annual and 5-year planning horizons, that have little to do with lifecycles (impacts) of real decisions.

- Cadence: Both use arbitrary annual planning cadence, that is suitable to decisions with lifecycles of 20+ years.

- Deterministic: Both are based on flawed assumption that the world is deterministic, when in reality it is probabilistic.

- Antithetical to learning: Adjustments are bureaucratic and rare.

- Incentives: Both have heavy incentives for ‘hitting the plan,’ whether it no longer (or ever did for that matter) makes sense to hit.

- Behaviors: Both create counterproductive behaviors that have negative consequences (inefficiencies, manipulation etc.) for the whole over the long-term.

- Focused on silos: Both are obsessed about closing all individual gaps between plan and actuals, assuming (falsely) that it leads to maximizing the performance of the whole.

In other words, odds are that many companies would find a person with extensive experience in the planning practices of the Soviet Union ‘fitting’ to their culture.

What’s Wrong with Planning in Many Companies Today

At first glance, the best practices for planning described by many finance experts sound straightforward and logical. It makes sense for the company to have strategic priorities, which must indeed be broken down into granular plans, supported by resource allocations and individual incentives.

And of course, you need to have an updated view of the latest situation, understand the drivers of differences, and take action to steer the company to reach its targets.

There’s nothing wrong with the general logic—other than that it’s like a house built on sand. It relies on the flawed assumption that it’s effective to capture reality in static deterministic plans that are updated annually. Unless this assumption holds true (which it doesn’t), the whole house of cards collapses.

In that case, the structure is steering the company efforts from real performance toward hitting plans disconnected from reality.

Related (click to open): Poor Practices Can Lead to Great Results

A common argument for annual or strategic planning is to name a successful company, perhaps from personal experience, and ask, “If these practices are so harmful, how do you explain all the great results?”

While there is a point—namely, that in the short term, the differences may indeed be negligible and, even in the midterm, not necessarily existential—that argument is akin to asking: if communism is such a bad idea, how did it sustain the second most powerful superpower for 70 years?

The Soviet economy’s long-term average annual growth rate from roughly 1928 to 1991 is generally estimated at around 2–4%, which was broadly comparable to the U.S. average of about 2–3% during the same period. Does that mean communism was as good (or even better) for a country, let alone its stakeholders, such as the people living in it, as free-market principles? Of course not.

However, that is exactly the same type of argument often given in favor of annual budgeting or strategic planning: “Look at these historical results.” Does that mean annual budgeting, or ‘strategic planning’ is as good (or even better) for a company, let alone its stakeholders, such as the employees, shareholders or customers, as alternative planning practices? Of course not.

The Issue with Static Plans

By definition, plans are coordinated sets of decisions designed to achieve specific targets based on specific assumptions, such as whether the market will grow or decline and by how much.

Static plans inevitably disconnect companies from reality because assumptions inevitably change, not all decisions are executed as planned, and new decisions arise outside the plan.

Even if none of that happens, the outcomes of assumptions and decisions are inherently probabilistic, not deterministic. This means it’s not only impossible to predict outcomes precisely, but results will differ even with the same ‘level of execution.’

When assumptions fail to materialize as expected, decisions deviate from the plan, and outcomes differ from projections, the plan ends up describing a version of reality that never existed—and never will.

Given the virtually infinite possible realities (how assumptions, decisions, and outcomes can unfold), the odds of static plans aligning with actual events diminish rapidly to zero over time, which is why in business context, holding on to such plan presents a Sophies Choice: whether to ‘hit the plan’ or improve performance.

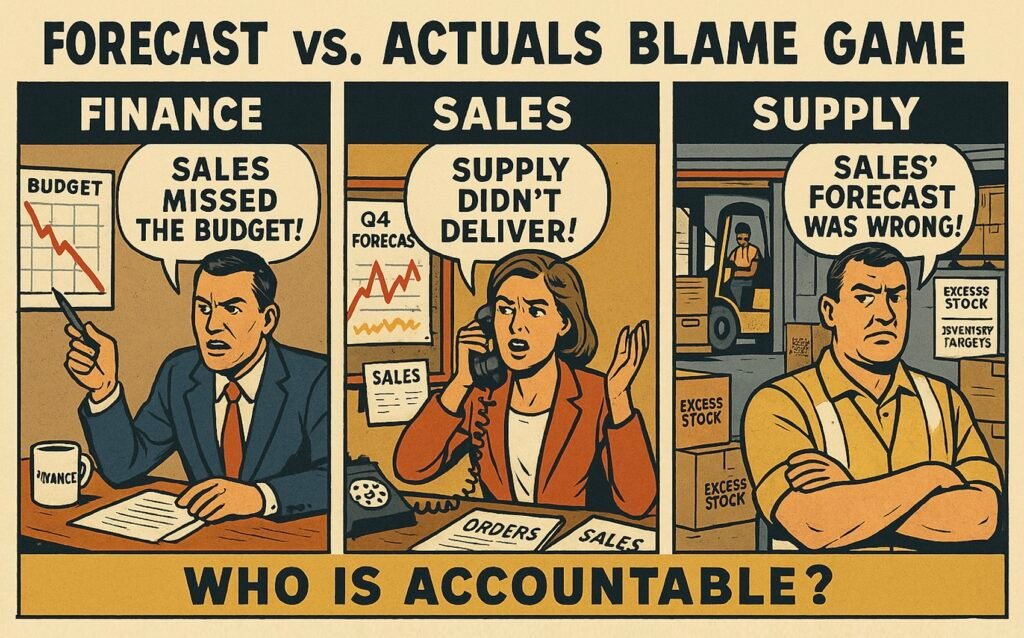

Counterproductive Behaviors

The practical consequence of the most common planning practices in companies is that they incentivize dishonest and counterproductive behaviors, ultimately undermining long-term performance.

The advantage of these practices is that they are effective in creating behaviors where people will do anything required (including lying and cheating) to ‘hit the plan.’ The disadvantage, however, is exactly the same.

Both approaches are focused on the trees but fail to see the forest: whether the plans still make sense to hit.

Because individual performance is evaluated based on the ability to hit a static budget, negotiations often center not on actual performance but on how to negotiate the largest hidden buffers in targets.

Top executives, aware of this dynamic, also build hidden buffers into their demands to counteract the business units’ buffers and allow flexibility when ‘things don’t go according to plan.’

This happens because, in traditional planning processes, performance is evaluated against what one was able to negotiate, not against reality.

For example, a business unit leader could have negotiated $100 million target based on the assumption that market grows 3%. She may hit the target even with worse performance if the market growth turns out to be better—say, for example, 5%.

Moreover, when hitting the plan is more important than real performance, it leads to short-term suboptimizations at the expense of the long term.

Common tactics include (but are not limited to):

- Paying to move future demand forward (e.g., through campaigns or discounts).

- Selling lower-margin or lower-quality products, even when the strategic focus is on premium, high-quality offerings.

- Running down inventories, leading to lost sales and overtime costs later.

- Cutting marketing or product development budgets to reduce short-term costs, regardless of their impact on long-term growth opportunities.

None of this aligns with the performance of the company in the long-term, let alone interests of the customers or shareholders.

The company would perform better if the time and effort spent on manipulating outcomes were used to improve performance, and if efforts were focused on critical challenges or opportunities addressed by the strategy.

Customers don’t need the products in December and would likely prefer innovations or new products delayed by cost-cutting measures.

Shareholders could do better if the company adhered to its strategic goals, growing sales through high-margin, high-quality products that fit its brand image, differentiate it from competitors, and align with its core capabilities.

Searching Signs of Alien Life from TV Static

As a corollary to the issues of static plans and counterproductive behaviors, running a variance analysis between the budget often resembles searching for signs of alien life in TV static, since the delta is not a reliable indicator of a real performance gap.

This is for two reasons:

- The target is a poor proxy for great performance: Since the original plan is typically the result of political negotiation rather than an objective representation of reality, the odds that it represents good performance are low. Even if it does, it is likely to become disconnected from reality over time as assumptions change.

- The actual is an unreliable indicator of real performance: The effects of random noise are often overlooked. Additionally, because the system is prone to gaming, actual results frequently reflect gimmicks that distort outcomes rather than represent true performance.

Put differently, much of variance analysis is a comparison of ‘what the performance wasn’t’ to ‘what the performance shouldn’t have been.’

This leads not only to gap-closing actions that address gaps that may not be worth closing in the first place but also to missing real performance gaps and failing to act on them in time.

Even if neither is true, it is still overlooked that focusing on the deltas of individual parts is not equivalent to improving the performance of the whole.

Free Market Principles

The purpose of this article is not to describe how free markets work, but it is worth pointing out a few characteristics that align well with effective planning practices.

For example:

- Outcomes are not pre-determined. The fundamental difference is that while a communistic system assumes that the future can be predicted precisely, free market principles are based on the opposite assumption.

- Adaptive actions: As a corollary to the fundamental assumption about outcomes, while operators in a communistic system are focused on realizing pre-determined outcomes, operators in free market systems are focused on making the best possible decisions at every moment, regardless of whether they result in the pre-determined outcome or not.

- Active learning: A free-market system is constantly learning and improving based on real-life data. In other words, it is inherently scientific: it continuously tests different hypotheses, allowing the ‘better’ ones to thrive and the ‘worse’ to diminish.

- Encourage risk-taking: Free markets encourage risk-taking by enabling higher returns to operators who take actions that may be unlikely to lead to successful outcomes, while a communistic system focuses more on whether individual efforts succeed or fail.

- Incentives: In free markets, individual incentives are more aligned with what is good for the whole, as the success of individuals depends on how beneficial other parts of the whole (other stakeholders) see the individuals’ actions. In a communistic system, the individual incentive is to hit the plan, which may or may not (often not) be seen as beneficial by other stakeholders.

Overall, the practical impact is that in free markets, the focus is much more on ‘real performance’—i.e., what produces the most real value—than on the ‘illusion of performance,’ i.e., producing outcomes that match what someone thought would be valuable 12 months ago or some other arbitrary number of months ago.

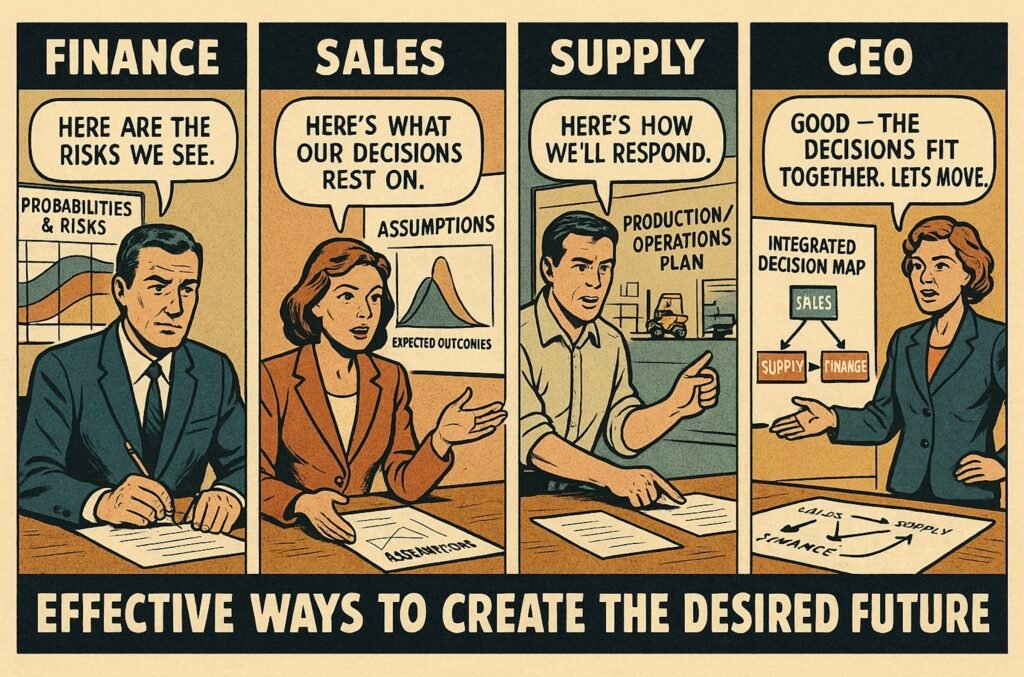

‘Free Market’ Planning Principles

The fundamental difference between alternative planning approaches and traditional annual or 5-year plans is that planning becomes a continuous process focused on ‘improving the odds’ of winning in the long term by learning and adapting, rather than a calendar-based event focused on ‘hitting the plan’ by sub-optimizing the short term and parts of the whole, without questioning whether that still makes sense.

What would that look like? In many ways it’s the exact opposite of the communistic version.

For example:

- Purpose of planning: To make better decisions in the present moment.

- Continuous: As a corollary to the above, decision-making is a continuous process, so planning must also be continuous.

- Focus on assumptions: To understand the real-life factors, such as market changes or competitor actions, behind the numbers.

- Target setting: Dynamic targets that remain relevant over time and account for decision impacts.

- Mechanism to revise plans: Scientific, meaning that the hypotheses outlined in plans are regularly tested and updated.

- Time horizon: Based on the lifecycles of real-life decisions.

- Cadence: Twenty times shorter than the typical decision lifecycle.

- Probabilistic: Explicit about the probabilities of targets, assumptions, and outcomes.

- Incentives: Aligned with the long-term performance of the organization as a whole.

- Behaviors: Encourage truthful reporting about business performance and focus on what matters for the organization’s long-term success.

- Adjustments: Agile, made when needed, but only when the benefits justify the effort.

- Focused on the whole: Not every delta of the parts is meaningful, and even sacrificing the ‘performance’ of the parts for the benefit of the whole.

While a detailed description of above is beyond the scope of this article, some of these properties are explored more, for example, in the following:

- Focus on decisions, instead of static plans.

- Characteristics of planning processes.

- Focus on assumptions.

- Target setting.

- Focused on improving the whole in the long-term.

These principles are not specific to any particular planning concept or acronym; rather, they are general principles that improve the ‘odds’ that planning drives business performance.

It’s similar to how there is no ‘one right’ way to eat and exercise, but there are fundamental principles for effective diet and exercise that apply across all successful programs, regardless of their names or the celebrities endorsing them.

Related (click to open): Why Are Alternative Planning Practices Seen as Theoretical?

Alternative planning practices are theoretical to many because few have practical experience of ‘free markets where there is no role accountable for setting prices.’

However, that’s more a symptom of the fact that subjective experience is a poor benchmark for what works than any kind of ‘proof’ that the idea doesn’t work.

It’s like how a physician from the mid-1800s might find it theoretical that a simple pill of antibiotics could be superior to bloodletting. Not only would the physician have to let go of something they’ve believed for ages, but understanding how a pill cures infections would require acquiring new information—like what bacteria are.

A similar lack of experience or knowledge is often why so many arguments against alternative planning practices are misconceptions or straw men—most of which stem from the mindset of ‘this is how we’ve always done it.’

One common argument (misconception #4) against continuous planning is that it takes too much effort. While that may be true if annual budgeting were simply extended to ‘budgeting 12 times,’ it isn’t the case when the real reasons why annual budgeting is so time-consuming are understood and addressed.

As a corollary to that, it’s quite common to argue that ‘endless planning’ leads to no action. This is also true—but it’s a straw man. In other words, it has nothing to do with planning. That’s like arguing it’s better not to drink water because ‘endless drinking’ could kill you.

Another popular ‘proof’ against continuous planning is that it often leads to mere updates of the plans, with little impact on the business. This is also true. However, what is equally often overlooked is that accountability for the continuous planning is typically delegated to a separate planning team or pushed down in the organization.

Meanwhile, those with real business accountability—such as sales or product management—often lack accountability for what goes into rolling plans, let alone what their consequences are.

Not only that, but most of their incentives remain tied to static plans. The real question, therefore, is not why rolling plans keep changing with little effect on the business, but why sales (or any other stakeholders, for that matter) would act against their own accountabilities and incentives.

However, where most struggle the most is in applying principles of probabilistic thinking. That is particularly difficult as it not only requires new skills—skills that take time and effort to acquire—but leaning into probabilities is psychologically challenging, as it shatters the illusion of predictability and control.

It is slightly ironic that what executives see as practical—setting deterministic numbers in stone far into the future—is, in fact, ‘theoretical.’ That is, if ‘theoretical’ means it doesn’t work well in practice.

What they see as theoretical—such as stating explicit probabilities of outcomes or assumptions—is, in fact, not only more aligned with the fundamental properties of reality but also leads to better outcomes in practice.

Not only that, but the ultimate irony is that what a communist finds theoretical in free-market principles—such as having no single role accountable for setting prices—is often the very essence that makes the free-market system more effective.

Similarly, it’s often those very aspects that make alternative planning practices, such as probabilistic thinking, more effective that executives find the least ‘practical.’

There are also a number of myths deeply ingrained in executives’ minds. One they like to repeat often is that “we are a public company, and therefore we have no choice other than to hit the quarter and annual estimates.”

While they have a point that attempting anything else is risky—since most current incentives are tied to arbitrary short-term results, and a company that is steered by the short-term attracts short-term investors, and as a consequence boards may draw their conclusion that the management team is incompetent and change—the belief that the stock market prioritizes companies hitting their guidance in the long term is a myth.

As outlined, for example, in Bain & Co research, the stock market cares far more—over 30 times more—about real performance than about whether a company hits its arbitrary projections.

Conclusion

How many companies are steered with annual and five-year plans resembles more how the Politburo managed the Soviet Union than how free markets operate.

One of the main similarities is the focus on creating and ‘hitting’ static plans, with all costs. The advantage of this is that it is effective in steering all the efforts in hitting that plan. The disadvantage is that the odds that the plan aligns with what is best for the long-term performance is virtually non-existent.

This presents both an opportunity and a risk for executives running modern companies. On one hand, if they are looking for ways to improve the performance in the long-term, there is a tremendous potential to move from ‘communistic planning principles’ to more ‘free market-oriented planning principles.’

On the other hand, if their performance is mostly evaluated not only by the short-term results, but the ability to hit the arbitrary targets (based on plans no longer aligned with reality), attempting such changes is a major personal risk.

While what is the best decision for each company, and each executive may vary case-by-case, in big picture the change is already well underway, as increasingly amount of companies are adopting more adaptive and continuous planning practices, under different concepts and acronyms.

The Soviet Union used annual and five-year plans for 60 years. The modern annual and strategic five-year plans have been widely used for about 50 years. It took 70 years for the Soviet Union to collapse, and it’s only a matter of time before annual budgeting and five-year ‘strategic planning’ corporate practices collapse as well.

There is, however, one valid reason to avoid alternative planning practices: they focus on improving the performance of the whole in the long-term, and therefore reduce the ability to manipulate short-term results.

Ironically, in public companies, there is no role with real accountability for that. As a result, the incentive to do what is best for the whole in the long term is often weaker than the incentive to suboptimize for the short term or individual parts of the whole.

If that’s your argument for planning like a communist, well, you just might be right to keep doing what you’ve been doing.

Practical insights

- Corporate planning often resembles planning in the Soviet Union.

- Thinking that outcomes can be precisely predicted is fundamentally flawed.

- Incentivizing ‘hitting a static plan’ will lead to counterproductive behaviors.

- Variance analyses are often like searching for signs of alien life in TV static.

- Alternative planning practices are more similar to free market principles.