Introduction

According to Rita McGrath, “Conventional planning approaches tend to focus managers on meeting plan, usually an impossible goal for a venture rife with assumptions. It is also counterproductive—insistence on meeting plan actually prevents learning.“

Many companies spend their time debating static numbers instead of understanding what’s really happening in the business. This focus has, at best, no impact on performance; at worst, it’s actively harmful.

In contrast, the more productive approach is to be explicit about the assumptions (real-world factors) behind the numbers—or better yet, behind the business decisions the organization has made and plans to make.

For example, $1 billion in sales might be a good result, or it might not. It depends on real-world factors, that one unavoidably makes assumptions about.

For instance, is the market going to grow or decline, and by how much? Are competitors launching new products or raising prices, and what will be their impacts? Will the organization’s new products be launched on time, and how will they affect sales?

Without context—i.e., without making the assumptions explicit—it’s pointless to debate whether the company will reach $1 billion or $2 billion in sales. The key question is: under what circumstances?

Similarly, without being explicit about the assumptions in advance, it will be impossible to say whether the decisions made were good or bad afterward.

A typical mistake is to argue that ‘anything can happen,’ and therefore it is ‘useless’ to assume anything. However, making assumptions is like breathing—no way to avoid it.

The only optional things are (1) how explicit the assumptions are, (2) how aligned different stakeholders’ assumptions are, and (3) how effectively people are able to continuously learn from them and use that knowledge to close future performance gaps.

What’s more, some executives still swear by ‘Dilbert-style management,’ believing it’s up to ‘execution’ to reach the static figures negotiated in the budget in all situations, regardless of the real-world factors.

While that may be possible, the right question is not how to reach them, but rather does it still make sense to reach them? And that depends. That depends on the assumptions.

The Problem

Companies often fixate on static numbers, like $1 billion in sales, instead of considering the assumptions that make those numbers realistic and challenging.

Focusing on numbers often results in forecasts that underestimate near-term possibilities and overestimate long-term potential.

In most companies, debates around numbers are unscientific because they lack the creation of hypotheses, careful testing, and the questioning of assumptions.

By definition, targets, decisions, and plans are valid only under specific assumptions. For the same reason, pursuing the same numbers and executing the same decisions when the assumptions are no longer valid will harm performance.

These issues stem from four key reasons: everyone makes assumptions, stakeholders’ differing assumptions hinder performance, assumptions may be disconnected from reality, and when they are, companies are unable to alter the course.

Everyone Makes Assumptions

As Rita McGrath wrote, “Even the best companies can run into serious trouble if they don’t recognize the assumptions buried in their plans.”

Executives are often reluctant to make their assumptions explicit because they may not be entirely sure what those assumptions are. Yet they fail to recognize that assumptions are unavoidable; making them is like breathing—everyone does it.

It’s impossible not to make assumptions, as this would imply that any target, outcome, or decision would be equally valid, making $1 billion in sales just as likely as $2 billion in sales under all circumstances, regardless of the decisions made.

That’s ‘stupid on its face,’ so there must be an assumption about the real-world context in which a specific number is a realistic and challenging outcome.

For instance, the sales figure of $1 billion is based on the assumption that the market will grow 10%. Whether this assumption is explicitly stated or implicitly understood, different growth rates could make $1 billion either unrealistic or unchallenging.

Even in a theoretical case where nothing is assumed about the market, and it could grow or fall by any amount, there is still an assumption that something will counter those effects, such as ‘everyone just needs to work harder.’

Similarly, all decisions rely on assumptions.

A decision to develop new sustainable products is valid under the assumption that the sustainable product segment will grow, and the legacy segment will decrease, but not if the opposite happens.

This is true for all decisions, even though it’s impossible to predict outcomes with certainty, and whether the assumptions are made explicitly or not.

Moreover, executives don’t just make assumptions; they actively use them, often as excuses for nonperformance after the fact, when it’s too late to affect outcomes.

For example, if new sustainable products sold $80 million while the assumption was $100 million, executives typically have no difficulty articulating which assumption had changed: ‘the market was down,’ ‘competitors decreased prices,’ or some department didn’t deliver as assumed by some other department, etc.

The only way ‘not to assume anything’ is to believe that there is never any reason for nonperformance, including blaming external factors like the market or other departments, such as product management for delays in launching new products.

Finally, implicit assumptions lead to a tendency to jump too early into solutions without fully understanding the problem or what makes the solution viable. In other words, executives may not realize how wrong they are until it’s too late.

Disconnected Siloes

Managers often cite misalignment across functions as the biggest obstacle to strategy execution, with only 9% saying they can reliably depend on other functions.

Differing assumptions among stakeholders can significantly hinder performance, regardless of whether those assumptions prove correct or not.

For example, the product team might assume the sustainable product segment will grow by 25% and that consumers will accept 10% price increases, expecting $100 million in sales.

Meanwhile, the sales team might assume lower 10% segment growth and doubt that consumers will accept any price increases, expecting only $70 million in sales.

This hinders performance because the teams’ actions will be misaligned. Even if the product team is correct, sales efforts might not focus on promoting sustainable products, and the sales forecast may not reflect high demand.

This can lead to lost sales due to insufficient efforts and poor availability, as operations may not stock enough products or invest in the required capacity.

Conversely, if the sales team is correct, the company allocates R&D resources based on inflated expectations, missing other, better opportunities to drive revenue growth.

Even if finance attempts to reconcile these views by estimating a compromise, say $85 million, the conflicting actions within the sales and product teams remain unchanged.

Furthermore, even if the reconciled $85 million estimate aligns with actual results, it may be due to a self-fulfilling prophecy—lower sales expectations might lead to insufficient resource allocation or capacity building.

One might ask why these issues can’t be resolved by simply aligning stakeholders on the numbers? While this would be a step in the right direction, it is not sufficient.

Even if both the sales and product teams agree on a $85 million sales target for new sustainable products without aligning on the underlying assumptions, their actions will still likely remain uncoordinated.

For example, they might differ on basic assumptions like segment growth. The product team might believe the segment will grow by 25%, while the sales team might think the segment will grow by 10%.

Since both cannot be right, this discrepancy indicates that other underlying assumptions are also misaligned. The product team might assume sales will acquire more new customers, while the sales team might assume faster market growth is based on sustainable products having superior functionalities to legacy products.

Even if stakeholders align on basic assumptions, such as the market growth, they may still disagree on the reasoning behind those assumptions. Suppose both teams agree on 25% market growth and a 10% price increase.

The sales team might still assume that new products novel features justify the price increase, while the product team might believe that the ‘sustainable’ label alone justifies the price increase, even if some features are inferior to legacy products.

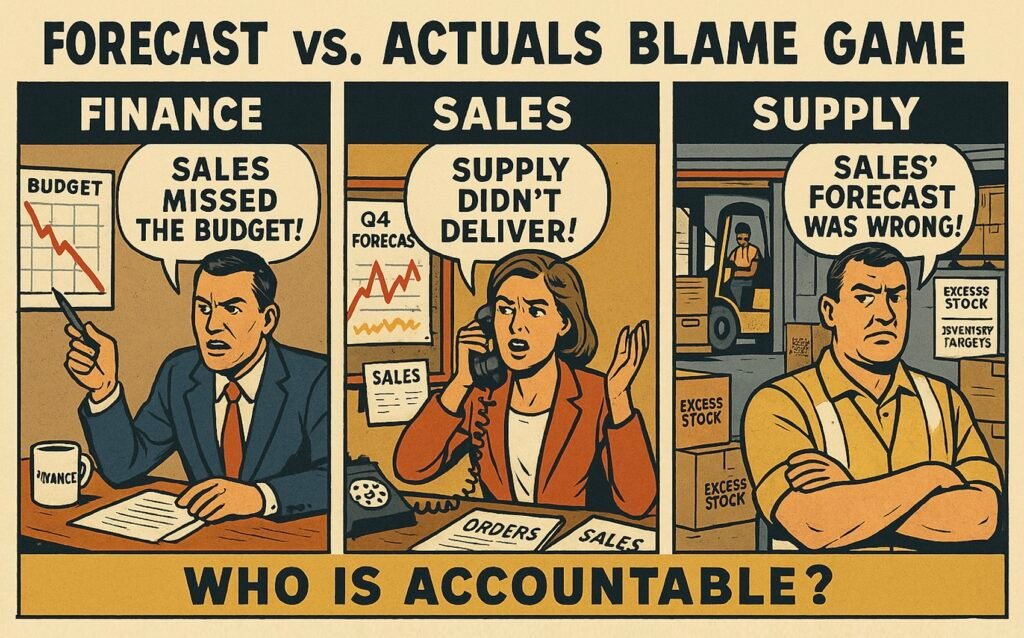

Differing assumptions are likely to cause stakeholders to blame one another: Sales might argue, ‘We couldn’t raise prices because the product team developed inferior products,’ while the product team might respond, ‘We missed investment targets because sales failed to enforce the agreed price increases.’

Disconnected from Reality

When executives fixate on numbers, even when they use market assumptions to justify a specific figure, the odds are that neither the numbers nor the assumptions reflect reality.

This is because the objective of the number debate is not to understand the business better, but rather to settle on the most favorable number for individual interests.

Therefore, planning that focuses on numbers often turns into a political negotiation aimed at compromise, rather than a process to understand reality and maximize performance.”

Lower-levels of the organization push for targets as low as possible, improving their chances of exceeding goals, maximizing bonuses, and career advancement.

For example, a business unit head might see the market growing by 5 to 8%, but she has an incentive to argue for a lower growth estimate, say 3 to 5%, to justify lower targets and create a larger buffer for uncertainty.

On the other hand, the top of the organization argues for the highest possible numbers to meet board and shareholder expectations, ensure maximum effort from the organization, and leave room for a ‘safety margin’ in case something goes wrong.

This can lead to absurd implicit assumptions, where ‘hitting the number’ may require achieving an unrealistic high market share, such as 85%.

This highlights the basic problem with static numbers, as noted by McKinsey: if developments in the marketplace are sufficiently different from the assumptions used, managers can’t make their numbers no matter what they do. Or, at worst: this leads to the company facing a crisis after being weakened by the hidden costs of all the short-term actions undertaken by managers endeavoring to make their numbers.

Even when assumptions are made explicit, they can still prove to be false.

For example, as described by Rita McGrath, Disney assumed that visitors to Euro Disney would spend an average of four days in the park, as they do in the U.S., but in reality, the average was only two days. They failed to account that while the U.S. parks had nearly 50 different rides, Euro Disney started with only 16, which visitors could cover in a single day.

Finally, according to McKinsey, since most companies’ projections are made by finance teams that are disconnected from the business, these numbers often contain built-in biases, inconsistencies, mistakes, and missing components.

For example, long-term revenue projections often rely on crude estimates of average pricing rather than real sales and marketing plans for future price increases. Or, assumptions about inflation rates may be missing or conflicting between cost and revenue estimations.

Whether intentionally misrepresented—by emphasizing negative assumptions while omitting positive factors, like market growth—or simply overlooking key details, such as the number of rides at Euro Disney, assumptions can easily become disconnected from reality, which means companies’ efforts are directed to the wrong direction.

Unable to Alter the Course

According to research, nearly one-third of managers say that the difficulty of adapting to changing market conditions is their greatest challenge in executing their strategy.

Focusing on numbers is a major reason why companies find it difficult to alter their course: it is antithetical to learning.

Static figures, such as $1 billion in sales, are unscientific because they leave no room for learning based on which assumptions turn out to be correct and which do not.

This is analogous to a scientist who decides the outcome of a clinical drug test in advance and is fixated on making the results support that, by any means necessary.

Failing to learn results in two major issues: the inability to determine whether poor performance is due to flawed decisions, poor execution, both, or neither, and a failure to update plans, recognize new gaps, and make right decisions to close them.

In many companies, “performance monitoring amounts to little more than reporting the weather.” Fixated on static numbers, they often obsess over “How did we perform?” instead of asking the more critical question: “Should we alter course?”

Consider the earlier example with new sustainable products. If the initial sales projections were $100 million and actual sales reached only $80 million, what conclusions should the executives draw?

Is the shortfall due to poor strategic where-to-play (WTP) choices or execution? If the former, was it because of inadequate market growth? Suppose the market grew by 25%. Was this growth more or less than expected, and by how much?

If it’s an execution issue, is the problem with the product itself, poorly executed projects, or insufficient sales efforts? For example, if sales assumed 10% growth and flat price increases, but they sold $10 million more than their expected $70 million, how was the issue poor sales efforts?

With just the numbers and without the real-world context they’re based on specified in advance, it is impossible to say. The core issue is that when executives rely on only numbers, ‘learnings’ afterward can be anything one wants.

Stakeholders may shift blame to external factors or each other. Sales might blame the product team for poor functionality, while the product team could blame sales for not raising prices, or both could fault external factors like ‘the market’ or ‘the weather,’ even when those don’t explain the gap.

This inability to pinpoint the real reasons for performance gaps prevents the organization from recognizing and addressing similar gaps in the future until it’s too late.

Say the performance gap of $20 million was due to ‘low segment growth,’ while the next year sales projections are based on the implicit assumption that the sustainable segment grows 25%, while the actual growth has been closer to 10%.

Failure to revise the assumptions in the plans means that the organization fails to recognize that there are similar $20 million gaps in the future for each year, and that the strategic WTP choice should be revised.

However, if the actual market growth of 10% had been assumed, the $20 million gap might have been due to insufficient sales efforts and stakeholder misalignment.

Instead of revising strategy and next year’s numbers based solely on poor performance, the organization should stick to the strategic choice, while focusing on improving sales efforts and cross-functional alignment.

Without clear assumptions, corrective actions are often based on subjective opinions, stakeholder negotiation skills, and personal relationships rather than objective business realities, resulting in poor performance.

The Solution

Instead of focusing on the numbers, executives should focus on the assumptions behind the numbers.

Rather than being fixated on deterministic outcomes, such as sales of $1 billion, and why they are ‘right’, or ‘whose number is right’, executives should focus on asking “what would have to be true for the option on the table to be a fantastic choice.”

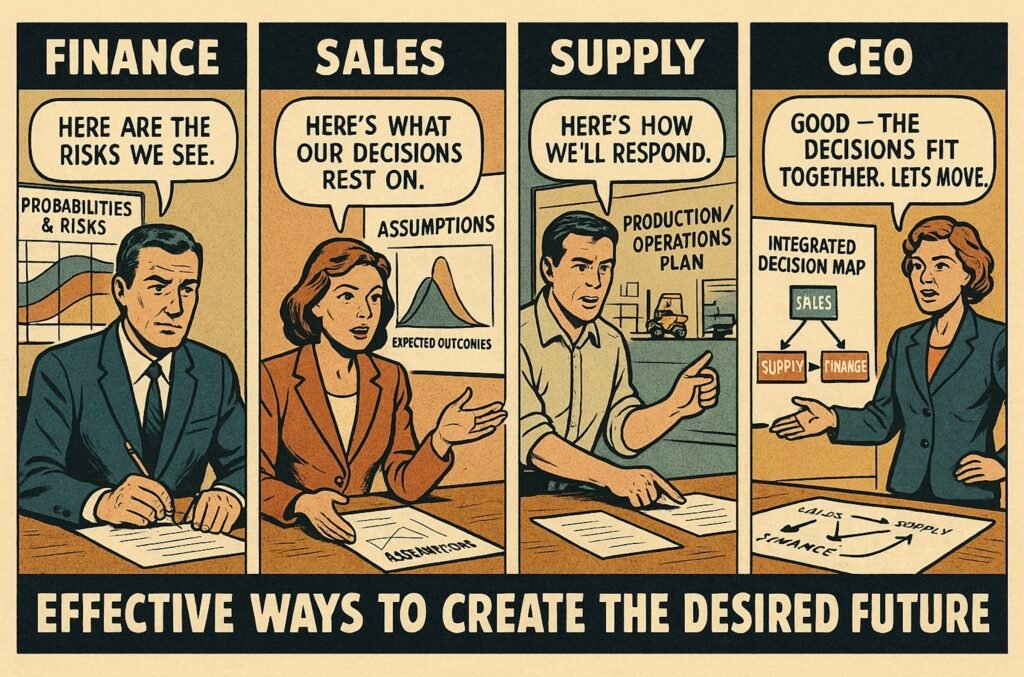

This means being explicit about the assumptions in the plans, debating those assumptions among the key stakeholders to gain alignment, testing the assumptions everyone commits to, and continuously learning and updating the assumptions and their implications to plans, meaning the numbers and decisions in them.

Make Assumptions Explicit

According to Rita McGrath, “Companies can learn to spot when they’re making unconscious assumptions.”

Executives need to shift from asking “What is the right answer?” to “What are the right questions?” They can achieve this by focusing less on the numbers in their plans and more on the assumptions behind the numbers.

These assumptions must be clearly documented; otherwise, aligning stakeholders, testing, and learning which decisions were sound becomes impossible.

This is because, as Ackoff and Martin have noted, without writing assumptions down, the human mind is prone to claim, ‘being right’ afterward, regardless of what the original assumptions that decisions were made against were.

A good place to start documenting assumptions is the reasons for underperformance.

For example, if an organization expected $100 million in sales from new sustainable products but only achieved $80 million, and the reason given is that segment growth was lower than expected, executives must explicitly state what they assume about the future segment growth.

The inability to predict segment growth precisely is irrelevant; the goal is not to find the ‘right answer’ but to foster debate and test the assumptions for continuous learning and adaptation as early as possible.

Let’s say the actual market growth was 10%, the sales estimate was $100 million, and the actual result was $80 million. If low segment growth is cited as a significant reason for the $20 million gap, then the segment growth assumption in the plan must have been higher than 10%.

Starting from reasons for underperformance is straightforward, as most executives are already using assumptions this way, but the downside is that it’s reactive.

A proactive alternative is to tell ‘a happy story about the future’ and ask, “What would have to be true?” Instead of debating whether new sustainable products will generate $70 million or $100 million in sales, tell a story about what conditions would need to be true for launching these products to be a good decision.

For example, segment growth might need to be 25%, and consumers would have to accept a 20% price increases, as the sustainable products have higher costs.

This approach works even in the highest level of uncertainty: ‘Level 4,’ where estimating a range of possible outcomes is impossible.

The key is to avoid the common pitfall of trying to prove assumptions right in advance or limiting them to what seems likely, as it’s impossible to prove what will happen, and unlikely scenarios may offer high returns.

As Roger Martin has explained, Aristotle observed 2,500 years ago that there are two parts of the world: one where things cannot be other than they are, and one where things can be other than they are.

Gravity is an example of the former. It remains constant, allowing precise calculations far into the future, such as predicting the trajectory of interplanetary objects.

A computer is an example of the latter. IBM chairman Thomas Watson is often misattributed with predicting in the 1950s that only five computers would ever be needed worldwide. In reality, demand grew to billions over the next 70 years.

While it would have been possible to predict the trajectory of an asteroid from the 1950s to the 2020s, it would have been impossible to predict how computers would transform communication, work, and entertainment during the same period.

The bigger the business decision, the more likely it falls into the category of things that ‘can be other than they are,’ meaning it’s impossible to prove in advance that the decision is ‘good.’ This is explored in more detail here.

Therefore, major business decisions are more about telling ‘happy stories’ about ‘what would have to be true’ and making the assumptions explicit, rather than attempting to analytically prove a specific outcome is ‘right.’

Although this may sound simplistic, Kaplan and Norton found that merely making the assumptions explicit improves decision-making compared to relying on short-term operational results.

Furthermore, there is evidence that simply describing the future can influence decisions made today, and research has shown that imagining an event has already occurred increases the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30%.

And even if one doesn’t believe in these specific benefits, making assumptions explicit is a prerequisite for aligning different stakeholders around them.

Debate the Assumptions

According to McKinsey, “the number one predictor of fast, high-quality decisions for big-bet, important decisions that companies make is the quality of the debate that goes into it.”

Mankins and Steele have found that high-performing companies approach planning differently. Rather than debating numbers, they focus on aligning assumptions with market realities to develop realistic and actionable plans.

High-quality debates require decision-makers to explore assumptions and alternatives, seek disconfirming evidence, and play devil’s advocate by offering counterarguments. Companies that do all three are more likely to outperform their peers in revenue growth.

Focusing the debate on assumptions, instead of numbers, makes it easier to create externally oriented and internally consistent forecasts across the organization.

As McKinsey puts it, “Effective finance leaders, in fact, recognize that a discussion about core assumptions is in itself a process that leads to better decision making.”

Regardless of the level of uncertainty, and regardless of which assumptions turn out to be correct, an organization can improve performance by aligning the assumptions of different stakeholders.

Consider the earlier example, where the product team assumes that the new sustainable products will generate $100 million in sales, but sales doesn’t believe more than $70 million.

Instead of debating whether the sales will be $70 million or $100 million, or debating only after the fact what the assumptions behind those numbers were, the question should be, ‘what would have to be true’ for the sales to be $70 million or $100 million?

Indeed, as Roger Martin suggests: “Managers must shift from asking “What do I believe?” to asking “What would I have to believe?”…and such a mind-set does not come naturally to most people.”

This approach keeps the focus on the real world, where the future can be influenced, instead of on arbitrary static figures or who is ‘right’—neither of which helps improve performance.

McKinsey research indicates that executives who are comfortable disagreeing with their leaders are 1.8 times more likely to report outperformance in revenue growth. Further, studies have shown that combining the views of several experts is more likely to yield accurate assumptions than relying on any single expert.

Therefore, it is likely that the mere discussion of several experts will result in more accurate assumptions, despite the fact it can never lead to precise predictions that are always right.

However, even if we wouldn’t believe in the wisdom of the crowds, the alignment (which doesn’t require agreement) alone would improve performance.

Say that both the product team and sales team are not convinced by the arguments of either side and stick to their own views. Executives should follow Jeff Bezos’ rule of ‘disagree and commit.’

This means that after hearing all arguments, the stakeholders commit (not necessarily agree) to a common view that will be tested.

For example, that to reach $100 million in sales, the sustainable product segment would have to grow 25%, and consumers would need to accept a 10% price increase.

This alone will improve performance, since the sales organization is now committed to focus its efforts on selling the sustainable products and it will reflect this view in the sales forecast, which means that operations is building capacity and stock for sustainable products.

Yes, there is still a possibility that the organization will fail if the assumptions turn out to be wrong, but the likelihood of success is now higher, regardless of what happens.

Unlike static numbers taken as facts—such as “sales must reach $100 million under any circumstances”—the organization has identified two real-life factors that can be tested: segment growth and consumers’ price sensitivity.

The fact that stakeholders don’t agree on these, and the fact that ‘anything can happen’ is irrelevant. Since it’s a characteristic of the real-world that it is impossible to precisely predict the future, no matter what, the organization needs to test the assumptions behind its plans and be willing to revise them based on real data.

Test Assumptions

According to Harvard Business School professors, ‘“Facts” come in two varieties: those that have been carefully tested and those that have been merely asserted or assumed. Effective decision-making groups do not confuse the two.’

Because the real world is unpredictable, no amount of debate will result in precise predictions or assumptions that are always right. This is why companies must continuously test their assumptions.

While covering everything on this topic is beyond the scope of this article, a few key points are worth mentioning.

First, assumptions must be measurable. When companies understand the importance of assumptions, a common pitfall is identifying them everywhere and going overboard.

For example, managers might describe as assumptions that the war in Ukraine will impact sales negatively by $10 million, the overall negative economic outlook will decrease sales by $50 million, and increased interest rates will reduce consumers’ purchasing power, thereby decreasing sales by another $20 million.

While all of the above may be relevant real-world factors that impact the organization’s performance, their impacts are not measurable—and that may be the reason why they are selected.

On one hand, the benefit of assumptions is that they enable a better understanding of where the performance gaps are. On the other hand, the downside of assumptions is that they enable a better understanding of where the performance gaps are.

Managers who are skilled in playing ‘budgeting games’ can view this increased accountability as a negative. Being purposefully vague about the market assumptions leaves more room to explain nonperformance through factors outside their control.

When assumptions cannot be measured—such as in the case of a $10 million performance gap—it’s easy to claim afterward that the ‘impact of the war in Ukraine’ was greater than expected. However, this does little to help improve future performance, since the ‘actual’ impact is another subjective assumption, not a real-world data point.

Therefore, assumptions should be measurable. For example, instead of listing vague factors like the war in Ukraine or a negative economic outlook, it’s better to be explicit about something concrete that they impact and what can be measured, such as market growth or competitors’ price changes.

Depending on the types of decisions, there can be significant risks involved, and it can be expensive to test assumptions.

To minimize the effort and costs, the organization should first test the assumptions that stakeholders are least confident about, or, depending on the magnitude of effort, alternatively, what is easiest to test.

For example, if the organization is least confident about the price sensitivity of consumers, it should test that first. If it turns out to be true, the likelihood of the entire hypothesis grows significantly, and if it turns out to be false, the organization should re-evaluate the decision.

Further, as Rita McGrath suggests, in the case of major decisions with high uncertainty, it is wise to set milestones that must be met before making bigger commitments.

For example, the organization may initially test assumptions about segment growth and price sensitivity with a limited product or in a pilot market before launching sustainable products across all product groups and markets.

Put differently, testing assumptions must be an iterative and continuous process, where current assumptions are continuously updated based on actual data.

It may also be wise to designate ‘intellectual watchdogs’ or ‘keepers of assumptions’ to ensure that assumptions are regularly checked and updated, as individuals under the pressure of daily firefights are unlikely to manage assumptions effectively on their own.

Update Assumptions

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

According to McKinsey, revisiting assumptions has always been a best practice. High-performing companies continuously revise the assumptions in their plans, enabling them to distinguish poor decisions from poor execution.

Instead of being stuck with a static outcome of $100 million, the organization should update the assumptions—and their impacts on outcomes—based on actual data.

Testing assumptions can lead to four outcomes: both the assumptions and their impacts are valid; the assumptions are valid, but the impacts are not; the assumptions are invalid; or new assumptions emerge.

For example, segment growth could fall between 20% and 30%, and consumers may be willing to accept a 10% price increase, meaning the company’s plans and decisions are valid.

More likely, some of the outcomes will be different. For instance, market growth could be lower or higher, at 15% or 35%, or price sensitivity could be greater or smaller, at 5% or 15%.

It’s also likely that some assumptions will prove valid, while new ones emerge. For instance, the assumption that new regulatory requirements will increase cost by 5% may prove inconsequential, while competitors’ pricing decisions could significantly impact sales.

When assumptions or their impacts change, a continuous feedback loop should be used to update assumptions in current plans.

This means that the performance management system, where differences between actual and estimated outcomes are evaluated, must be an integral part of the planning system that generates plans.

Whenever they are different, the planning system will generate plans that quickly become disconnected from reality, while real gap-closing decisions are made elsewhere.

In practice, updating assumptions means systematically repeating three steps: make the assumptions explicit, debate them, and test them.

Actual outcomes reveal discrepancies in existing assumptions, debating them improves accuracy and aligns the organization, and testing them makes them more robust.

If real market growth is 10%, not the assumed 25%, the organization should incorporate this new information into future plans. The same applies if it’s recognized that competitors are offering heavy discounts, rather than doing nothing as implicitly assumed in the plan.

As a result of these updates, the organization will identify future gaps earlier and adjust its decisions, rather than holding on to static outcomes, like $100 million in sales, and attempting to ‘gap close’ that.

Without systematically updating assumptions, companies make decisions to ‘gap close’ $20 million, through short-term cost cuts that harm long-term growth.

By updating assumptions, the company will not only see the real gap, but also identify which decisions need revision.

Let’s say actual sales were $80 million, while the expectation was $100 million, and the core assumptions were valid: the segment grew 25%, and consumers accepted a 10% price increase.

When the core assumptions for the strategic WTP decision (in the sustainable product segment) turn out to be true, performance issues are likely in the execution of that decision.

For example, it could be a lack of sales effort or poor availability, or problems with executing NPI projects. However, without making the assumptions explicit in advance, the company might blame ‘poor execution,’ even if the segment grew only 10%.

In that case, the organization should review the WTP decision and possibly revise it, as the context in which it made sense for the organization to be in that business has changed from what the decision was based on.

Focus on the assumptions, Not the Numbers

Assumptions reflect real-world factors, like market developments, while static numbers—such as $1 billion in sales—often result from political negotiations.

Focusing on assumptions not only requires but leads to a better understanding of real-world dynamics, while focusing on static numbers doesn’t require such understanding and likely leads to disregarding reality.

Obsessing about static figures, while ‘not assuming’ anything, means logically that any outcome is equally likely, regardless of the decisions made, and there are no reasons for nonperformance, under any circumstances, which is ‘stupid on its face.’

Therefore, executives need to make a choice. Either they have to accept any outcome and stop ‘explaining’ performance gaps after the fact, or they must make explicit the assumptions under which their plans are valid.

It logically follows that different stakeholders must align (commit, not necessarily agree) on those assumptions to avoid performance losses from misaligned decisions.

Since it’s impossible to predict which assumptions will hold true, executives must continuously test them, revising plans based on real data to identify performance gaps early and make better decisions.

A prerequisite for this is ensuring that planning systems align with real business decisions and incorporate a continuous feedback loop from actual data; otherwise, companies won’t be able to understand the full impact of those decisions or update plans when assumptions change.

Practical insights

- Change focus from numbers to assumptions behind the numbers.

- Make assumptions explicit because everyone makes them anyway.

- Debate the assumptions to gain alignment among different stakeholders.

- Test the assumptions based on actual data to base them in reality.

- Update the assumptions of the future to identify and close gaps earlier.