Introduction

After thousands of books on the subject, there is still no consensus on what strategy actually is. However, although many of the details vary, according to many definitions and most strategy experts, strategy guides the rest of the choices made by the company.

Whether it is a guiding rule, as defined by Richard Rumelt, a unique positioning as defined by Michael Porter, or an integrated set of choices—like where-to-play and how-to-win—as defined by Roger Martin, a key purpose of strategy is to create focus by choosing what not to do.

Similarly, most strategy experts agree that planning is important in implementing the strategy. However, while they focus on definitions of strategy and how companies can create an effective strategy, they often fail to recognize how common planning practices limit the usefulness of carefully crafted strategy.

Peter Drucker is often misquoted as having said that ‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast,’ and there is certainly some truth to that. If a company has a command-and-control culture, crafting a strategy that requires empowerment of employees to make decisions on the front lines is doomed to fail, regardless of how brilliant it otherwise is.

However, while many people recognize the possible constraints that a culture may impose on how effective a strategy can be, far fewer recognize that, in most companies, there is one even more powerful mechanism that ‘will eat strategy for breakfast.’ Namely, the Annual Budgeting Process.

Annual Budgeting Eats Strategy for Breakfast

What’s the most common question in companies all over the world?

Well, who knows for sure, but “Are we on the budget?” has to be quite high on the list.

The logic is straightforward. Most companies tie their incentives, including annual bonuses to the budget, and as a consequence the executives and managers become highly interested on whether the company is still on track with it.

And if it isn’t, their next question is “how are we going to close the gap?”

Sure, there are some exceptions that don’t even have an annual budget and some who are laser focused on the strategy (the big choices or guiding rules) that override the budgets.

However, for the vast majority, the number one focus is on tracking the progress against the budget and executing action plans to close those gaps.

So, what’s wrong with that?

Well, maybe nothing, but the odds are, a lot.

Finance experts will argue that the budget is a tool to implement the strategy. It is how the company can ensure it is on the track with the strategy.

And while it’s a comforting theory, as it provides an illusion of control, it doesn’t work particularly well in the real world.

Some of the reasons why, include:

- Incentives are to ‘hit the budget,’ not to implement strategy.

- Budget has a 12-month time-horizon, strategy doesn’t.

- Strategy is a living thing, annual budget, isn’t.

Since the budget is, or inevitably will become, disconnected from the strategy, the executives are faced with a Sophie’s choice: whether to implement the strategy or whether to ‘hit the budget.’

And since most, if not all, incentives are in hitting the budget, it’s not really a tough choice or even a choice at all. The budget is in practice what steers all the decisions in the company, not the strategy, regardless of the framework used to formulate it and regardless of how brilliant it may otherwise be.

Case Study: The Conflict Between Strategy and Budget

Consider a case of an organic snack company operating in the natural food industry. Its strategy is centered on three key choices:

- Winning Aspiration: To lead the premium organic snacks market as the first choice for urban millennials seeking sustainable snack options.

- Where-to-Play: Targeting affluent urban millennials who value sustainability and organic products.

- How-to-Win: Differentiating through product innovation and a premium brand built on transparency and ethical sourcing.

To execute this strategy, it:

- Invests in R&D to develop innovative organic snack options.

- Builds strong relationships with sustainable suppliers, ensuring a consistent supply of premium ingredients.

- Allocates marketing spend to educate consumers about their brand values and sustainability practices.

While the budget may initially reflect the strategy, as the year progresses, the executives face increasing pressure to meet annual revenue and profit targets. Sales are lagging due to slower-than-expected market growth and a delay in launching a new product line.

In a budget review meeting, the CFO concludes that unless drastic measures are taken, the company will miss its budget targets.

To ‘hit the budget,’ the management team takes several actions that violate their strategic choices:

- Product Expansion: In an effort to increase revenue, the company introduces a lower-cost product line that appeals to a broader audience. This move diverts resources from their core premium offerings and confuses their brand positioning, alienating their target audience.

- Supplier Substitution: To cut costs, they switch from their high-cost sustainable suppliers to cheaper conventional ones. While this move reduces costs and improves margins in the short term, it undermines their promise of ethical sourcing, eroding consumer trust.

- Price Discounts: The marketing team launches aggressive discount campaigns to boost sales volumes. These discounts dilute the brand’s premium positioning and train customers to wait for promotions instead of paying full price.

- R&D Cuts: To preserve profitability, the company freezes its R&D budget, delaying the launch of its innovative snack line. This decision compromises their ability to sustain differentiation in the future.

By the end of the fiscal year, the company successfully ‘hits the budget.’ However, in doing so, they have in practice changed their strategy:

- Where-to-Play Change: The introduction of a lower-cost product line shifts company’s focus away from affluent urban millennials to a broader, price-sensitive audience. This dilutes their original “where-to-play” choice, weakening their position in the premium market.

- How-to-Win Change: By substituting suppliers and focusing on discounts, company sacrifices product quality and brand integrity. This undermines their differentiation based on transparency, ethical sourcing, and premium quality, effectively abandoning their “how-to-win” choice.

In other words, while these changes enable the company to ‘hit the budget’ in the short term, in the long term, the dilution of strategic choices makes it harder for the company to create unique value and differentiate itself from the competition.

In effect, their real strategy becomes ‘do whatever you have to do to hit the arbitrary static budget numbers,’ which is essentially the exact same ‘strategy’ that many of their competitors have.

This makes it harder for them to grow in the long term, as they are competing with ‘operational excellence,’ not with a unique value proposition.

What to Do Instead

In practice, executives need to make a choice: which is more dynamic, the strategy or the budget? If a company wants to have a strategy—meaning a strategy that steers the business in practice, rather than collecting dust in drawers—the budget needs to be dynamic.

This means returning to the original purpose of the budget: a financial interpretation of the business plan. And the business plan is widely thought to represent how to implement the strategy.

For some reason, over time, the roles have reversed. The budget has become the dog, wagging not only the business plan but also the strategy.

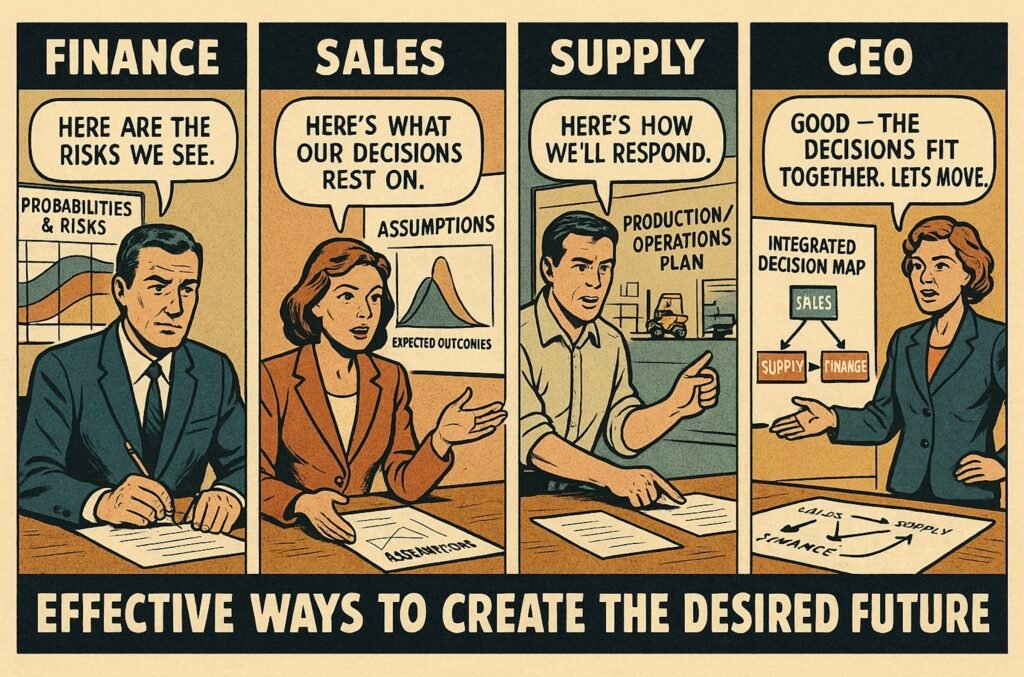

To keep the strategy dynamic, companies should:

- Set dynamic targets that address strategic challenges or opportunities.

- Implement a continuous resource allocation process.

- Focus on the assumptions instead of the numbers.

- Focus on improving the odds of winning instead of ‘hitting the plan.’

The budget has two main purposes: target setting and resource allocation.

Traditionally, both are static or, at least, very rigid. If companies wish to hold on to their strategies, both need to become much more dynamic. Put differently, they need to be ‘the means to an end,’ not the end itself.

The reason why both are so rigid is that the budget focuses on the number outcomes.

Although there are often assumptions about the real-world context behind the numbers, they are typically used as political negotiation chips, rather than tools for aligning the numbers with reality.

Therefore, the key to making budgets more dynamic is to focus more on the assumptions behind the numbers and to update those assumptions as reality changes.

Finally, while traditional annual budgeting focuses on producing a plan that is then followed at all costs (the outcomes, not necessarily the content), putting strategy in the driver’s seat requires a different focus: continuously making better decisions, even if the outcomes cannot be precisely controlled.

In other words, it means concentrating on improving the ‘odds of winning.’

Set Dynamic Targets That Address Strategic Challenges or Opportunities

To be able to hold on to strategic choices, instead of chasing static annual targets, executives must use dynamic targets that account for decision impacts and address critical strategic challenges or opportunities.

A key opportunity for an organic snack company with an annual revenue of $900 million could be to capture a bigger share in the sustainable organic snack segment by differentiating the brand with transparent and ethical sourcing.

Therefore, instead of setting a static annual target of $1 billion or $990 million (+10%), a realistic and challenging target could be to grow market share from 20% to 25% in four years.

If the market were to grow 5% as assumed, that would result in $1 billion in sales after a year. However, if market growth were higher, for example 10%, it would result in $1.05 billion in sales after a year, or $960 million in sales if the market were flat.

By not having to focus on ‘closing the gap’ to the arbitrary static number, the company could focus on implementing its strategic choices, which would lead to higher performance over the long term, which is the very reason to have a strategy.

If the company can find a better set of strategic choices, it may, of course, change them. But that should be based on evaluating the business logic behind the choices, not dictated by whether the company is able to hit an arbitrary budget number by the end of the fiscal year.

Implement a Continuous Resource Allocation Process

To implement strategic choices—such as targeting millennials who value sustainability and organic products, differentiating through product innovation, and building a premium brand based on transparency and ethical sourcing—a company must invest in R&D, build strong relationships with suppliers, and educate consumers about its brand values and sustainability practices.

However, these decisions cannot be made just once a year; they must be made continuously.

The company cannot know in advance how many products it should launch, which technologies to invest in, how many people to hire, or how much to spend on building the brand.

To do this effectively, it needs a dynamic resource allocation process that continuously updates its view of the future, evaluates the effectiveness of its decisions, revisits the core assumptions behind those decisions, and allocates resources accordingly.

The planning cadence of such a process must align with the nature of typical resource allocation decisions. While this may vary by industry, most resource allocation decisions impacted by annual budgeting have lifecycles spanning multiple years.

For instance, decisions like launching new products, which involve multi-year commitments, require at least a bi-monthly cadence and often benefit from even monthly cadence. Conversely, the annual cadence most companies use is better suited to decisions with lifecycles of 20 years or more.

Additionally, for resource allocations to be effective, the process must consider their long-term impacts, which in most cases extend several years beyond the calendar year.

The best time horizon for an individual company will vary by industry, but as a rule of thumb, for most companies, it likely falls somewhere between 2 and 5 years.

The key difference from traditional annual budgeting is that extending the time horizon from a shrinking calendar year to a rolling 2 to 5 years increases the coverage for understanding decision impacts by 300% to 900%.

The uncertainty surrounding these impacts is irrelevant, as the company is making those ‘bets’ regardless.

It’s about ‘improving the odds to win.’

Increasing the cadence from 12 months to monthly decreases unnecessary delays to agility by an average of 6 months.

But the goal is not merely to change the cadence and time horizon.

Companies need to rethink the purpose as well.

Originally, budgets were a financial interpretation of the business plan—a means to an end. In typical annual budgeting, however, they’ve become the end itself.

It obviously doesn’t make much sense to set static budget constraints for Q4 2025 in Q4 2024. But there is value in having a financial interpretation of the business plan for Q4 2025, and even for 2026 or 2027, because companies make decisions that have cost and revenue impacts that far into the future.

Better understanding these impacts enables companies to make the best possible resource allocation decisions and constantly improve their performance.

Focus on the Assumptions Not the Numbers

When strategy is what wags the tail, instead of the annual budget, planning should be more about the assumptions than the precise number outcomes.

Instead of being fixated on static numerical outcomes, such as sales of $1 billion, or even the market share of 22%, the company should be more focused on the assumptions behind those numbers.

Consider the earlier example of organic sustainable snack company which has a winning aspiration to lead the premium organic snacks market as the first choice for urban millennials seeking sustainable snack options.

Instead of debating whether the sales will be $1 billion or $1.1 billion, or even whether the market share will be 22% or 23%, the question should be ‘what would have to be true,’ for the strategic choices to be good?

For example, what would have to be true, that the choice to differentiate with ethical and transparent sourcing is good?

Sure, one could argue that being transparent and ethical are ‘good’ choices on their own, but in this context the more specific question is how is it good in making its winning aspiration to become true?

For instance, improving transparency and ethicality of sourcing is a ‘good choice’ if it is decisive criteria how the targeted millennials choose their snacks.

Focusing on what drives the millennials choices, is more valuable than focusing on what the exact sales of a specific year will be. By creating more unique value, the numbers will follow.

Continuously revising future assumptions enhances the company’s ability to predict outcomes, recognize performance gaps early, and make necessary decisions sooner—ultimately improving performance.

Focus on Improving the Odds to Win

Resourcing decisions are rarely ‘safe bets.’ And even if there were such a thing, companies have numerous different possibilities for how to allocate their resources.

An organic snack company focused on premium sustainable products needs to invest in launching new products and building its brand, but it can never be absolutely certain—or even highly confident—which products or marketing initiatives will succeed, let alone what the precise impacts on the company’s financials will be.

To find out, it needs to experiment.

Therefore, for resource allocations to be effective, they must focus on improving the odds that decisions will ‘win’ by learning and adapting, rather than predicting the unpredictable and obsessing over ‘hitting the plan.’

Instead of focusing on deterministic point outcomes, such as $10 million, the company should use probabilities that cover all possible outcomes.

For instance, for a specific new product launch, there may be a 25% probability that sales will be $8 million or less, a 50% probability that sales will be between $8 million and $12 million, and a 25% probability that sales will be $12 million or more.

Similarly, instead of stating that the assumption of future segment growth is 5%, the company should say there is a 50% probability that the segment growth will be 5% to 10%, a 25% probability that it will be less than 5%, and a 25% probability that it will be more than 10%.

While individual outcomes will vary, the company as a whole will perform better when it improves its understanding of the underlying likelihoods behind its decisions.

At the company level, this means allocating resources to those business units, functions, or initiatives that improve the expected value of the total. For example, reallocating $10 million from product launches to brand building.

Conclusion

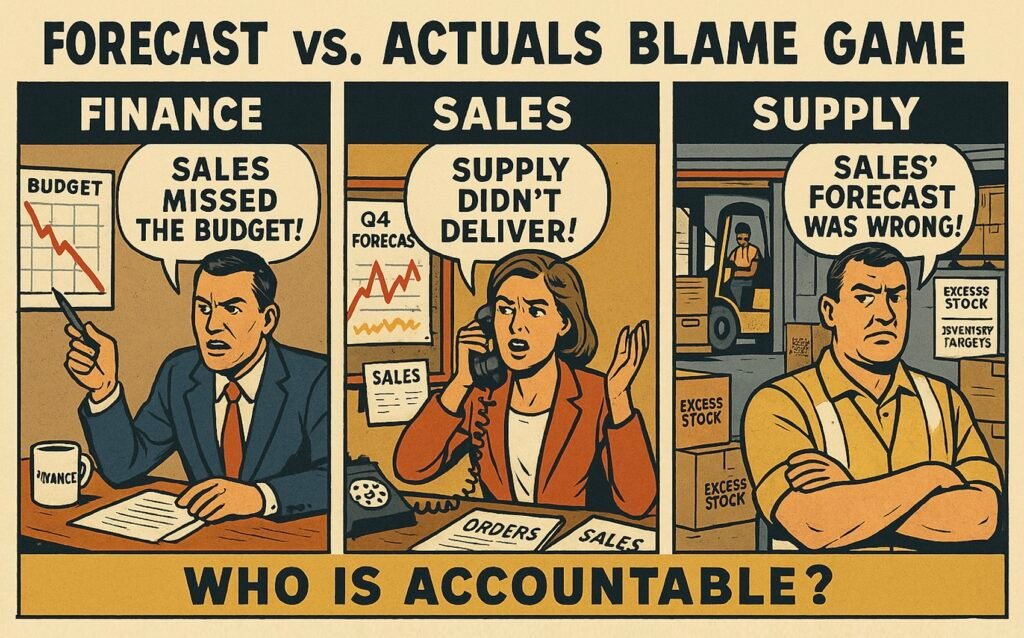

Companies running traditional annual budgeting are likely to derail from their strategies over time.

This happens because the characteristics of annual budgeting create an obsession with ‘hitting the plan,’ rather than making the best possible decisions based on the strategy.

Both strategy and the annual budget share a similar purpose: guiding the decisions executives and managers make. However, the problem is that the way they guide decisions is rarely aligned.

Strategic choices create fit and focus on how the company delivers unique value to specific types of customers. In other words, strategy is about choosing what not to do.

By contrast, the budget does not restrict the choices a company makes in any strategic way. Instead, it only limits the choices based on precise outcomes tied to precise timelines.

This means that, when following the strategy, many of the choices needed to ‘hit the plan’ are not possible. Conversely, many of the choices that enable ‘hitting the plan’ are not aligned with the strategy.

Ultimately, executives must decide what matters more: having a strategy that maximizes the odds of the company ‘winning’ in the long term, or ‘hitting the budget’ and allowing that to dictate the strategy—along with the company’s odds of long-term success.

Practical insights

- To have a strategy, companies cannot have annual budgeting.

- Strategy implementation requires dynamic targets in the short-term.

- Strategy implementation requires dynamic resource allocation.

- When implementing strategy, focus on the assumptions, not the numbers.

- Strategy implementation is about ‘improving the odds to win.’