Introduction

Charles Munger and Warren Buffett used to say: “95 percent of behavior is driven by personal or collective incentives”, only to later correct themselves: “95 percent was wrong; it is more like 99” (as cited in Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick).

Many leaders claim to have a growth strategy but struggle to grow and wonder why, often blaming the execution. At the same time, they set targets that not only fail to incentivize long-term growth but actively incentivize to kill it.

As the MythBusters used to say: “Well, there’s your problem.”

In most companies, target setting incentivizes people to lie, cheat, and sub-optimize the short-term rather than maximize business performance and long-term growth.

Executives obsess hitting set targets, even at the expense of improving the company’s performance. The major reason for this is the misconception that a shareholder’s valuation of the company is determined by whether it hits the targets.

In reality, as shown by Bain & Co research on almost 4,000 companies, actually improving performance is 35 times more important for total shareholder return than hitting the predicted static numbers companies have communicated.

And according to McKinsey, organizations that prioritize long-term value creation over short-term profits are nearly twice as likely to outperform competitors in terms of growth and return on capital.

Traditionally, target setting is based on static absolute figures from the Annual Budgeting Process (ABP).

Due to the unpredictability of the real world, static absolute targets—such as $1 billion in sales—encourage dishonesty about how realistic it is to achieve them when negotiating the targets.

Static figures are realistic and challenging only under specific assumptions, i.e., real-world factors such as whether the market is growing or declining.

Since these assumptions constantly change while the targets stay the same, it is a matter of luck whether the targets become unrealistic or unchallenging. The odds that static absolute figures will remain realistic and challenging over time are essentially non-existent.

This represent a Sophie’s choice for the executives: whether to hit the targets or make the best decisions to improve the company’s performance?

The good news is that the characteristics of target setting are entirely within the organization’s control and can therefore be addressed.

The Problem

Executives push companies to meet targets but fail to recognize that these targets may not only be unworthy of reaching but could also be the root cause of killing growth.

Often, targets reflect a mixture of political power, negotiation skills, and luck rather than being realistic, challenging, and aligned with how the company’s resources should be directed to maximize its chances of success. This creates a Sophie’s Choice for managers: whether to meet their bonus or do what is good for the company in the long term.

Even when initially sensible, these targets often become disconnected from reality as the underlying assumptions change, making them either unchallenging or unrealistic to achieve. This incentivizes bad behaviors, such as lying and cheating, or even creates a culture where “it becomes the norm that performance commitments won’t be kept.”

Ironically, poor target setting can even lead companies to celebrate underperformance as overperformance, without realizing their targets were flawed from the start due to four key factors: they aren’t based on reality, difficulty is influenced by luck, there’s a bias toward short-term costs, and different levels of difficulty are treated the same.

Targets Are Not Based on Reality

Executives often set ambitious targets based more on hope than on reality, relying on rules of thumb, such as 10% increase, psychologically satisfying numbers like $1 billion, or political compromises.

Richard Rumelt refers to such targets as “Dilbert-style corporate management” because they are disconnected from the reality of the situation—arbitrarily set rather than grounded in an understanding of critical challenges and opportunities.

In addition, as Janet Bannister notes, companies often miss critical nuances when they mandate uniform 10% expense cuts across all departments.

For example, an organization may set a sales target of $1 billion because it is a nice round number and a significant stretch from current sales.

However, if the organization’s where-to-play choices remain the same as the past decade—focused on mature markets with already high market shares—reaching $1 billion could mean acquiring an absurdly high market share, like 85%.

The fact that the most important targets—those the organization cares about most—are typically static figures while the real world is probabilistic creates an incentive to sandbag them, building in buffers for uncertainty.

What makes matters worse is that targets are typically tied to annual bonuses, which exacerbates these bad behaviors. Sandbagging from the bottom leads top executives to push for stretch targets that are not based on anything in the real-world.

The underlying issue is that people know they will be measured and rewarded based on what they say they can achieve rather than on actual performance.

For instance, a business unit leader might be measured against a static sales target of $100 million, which she successfully argued for based on a conservative 2% market growth expectation. However, when the market actually grew by 5%, even though she exceeded the target, the company lost market share to competitors.

As a result, final target numbers are more likely to reflect the political power and negotiation skills of different stakeholders rather than the reality of the situation.

Moreover, setting aggressive stretch goals that are not based on reality can have damaging repercussions, as it may amplify poor behaviors.

For example, Michael C. Jensen illustrates this with a case where a new CEO of a multinational corporation learned the hard way when his attempt to counter suspected sandbagged targets backfired.

As business unit managers realized the stretch targets were unattainable, they deferred revenues and profits, deteriorating current-year performance in hopes of more realistic targets the following year.

Even if targets are initially based on reality, they’re unlikely to remain so over time as underlying assumptions inevitably change.

Level of Difficulty Is Influenced by Luck

Bjarte Bogsnes illustrates the absurdity of static absolute targets with a football team aiming to score 45 goals next season. Similarly, sales of $1 billion might not reflect good performance in every scenario.

Consider a company targeting $850 million in sales from legacy products and $100 million from new sustainable products.

If legacy product sales are based on flat market growth, a 3% variance in market conditions could result in sales ranging from $825 million to $875 million.

Similarly, if sustainable segment growth is projected at 20% to 30%, outcomes could range from $95 million to $105 million.

Thus, depending on market developments, total outcomes of $920 million, $950 million, or $980 million could all be as realistic and challenging targets.

Conversely, setting a static total target of $950 million makes the difficulty level dynamic. While this target is realistic and challenging when the legacy market is flat, it would require 3% higher performance (equivalent to an additional $30 million in sales) if the market declined by 3% and would allow for 3% lower performance (or $30 million less in sales) if the market grew by 3%.

If 3% better performance is possible during a downturn, 3% lower performance should not be acceptable when the market is up, as it would mean leaving money on the table.

On the other hand, demanding 3% (or $30 million) higher performance above what is already realistic and challenging could lead to missed targets, dissatisfied employees, or short-term moves like heavy discounting that hinder future growth.

Similarly, a company’s financial performance may be influenced by macroeconomic factors such as the U.S. inflation rate and the USD/EUR exchange rate, both of which are beyond the company’s control.

A profit target of $100 million, realistic and challenging with 2% inflation and an exchange rate of 1.1 USD/EUR, could become unrealistic if inflation rises to 5%, raising production costs, and the exchange rate shifts to 1.3 USD/EUR, lowering international revenues.

The fact that companies cannot control many of these core assumptions, and that makes the level of static targets dependent on luck, results in a subtle yet rapid cultural shift: unrealistic plans create a norm where commitments are not expected to be fulfilled.

According to Mankins and Steele, over time, this fosters a culture where managers focus on self-protection rather than improving performance, diminishing the organization’s capacity for self-criticism and harming overall performance.

Short-term Cost Bias

Why are marketing costs always the first to be cut when the profit target is in danger?

Most performance management systems focus on short-term financial measures, neglecting long-term strategic objectives. This narrow view fails to provide a holistic picture of the company’s real performance, as many strategic decisions can’t be tracked solely through financial targets.

Moreover, many companies set targets—especially those tied to bonuses—based on these short-term financial measures, while executives are not typically held accountable for achieving strategic objectives.

This leads to two main issues: first, a bias toward short-term cost-cutting in targets and incentives; second, a culture where it is not only accepted but expected that strategic plans are ignored, and strategic objectives are unmet.

Without accountability for these shortfalls, the cycle of failure repeats for years, leading to familiar patterns like ‘Venetian Blinds’ or ‘Hairy Backs,’ or worse—to be a little dramatic—a culture of short-term cost bias.

The root cause of this short-term myopia often lies in the characteristics of executives’ planning processes, particularly the artificial 12-month horizon in ABP.

As discussed elsewhere, when decisions are made continuously, as they typically are, ABP captures at best only 20% to 25%, and at worst, only 1% to 2%, of the impact of resource allocation decisions with a commitment time of 4 to 5 years.

Conversely, the 12-month horizon suits decisions with a 6-month commitment time on average, though even then, it fails to capture the full impact half the time.

This means that targets set for a 12-month period often fail to capture the true impact of major decisions, incentivizing short-term cost cuts and causing a misalignment between hitting targets and maximizing performance.

Since costs occur upfront while revenues come later, setting targets, and especially incentives, only for the first 12 months creates a bias toward cost-cutting, at the expense of long-term growth.

This is why marketing costs are the first to be cut when profit targets are at risk: costs are short-term, while revenues are long-term. When targets ignore long-term growth, short-term profits can be artificially inflated to hit the targets.

Different Levels of Difficulty Are Treated the Same

“Don’t play for safety – it’s the most dangerous thing in the world.”

All targets have an inherent level of difficulty, yet this is often not considered in target setting. While executives expect risk-taking, they often not only fail to reward it but instead reward risk-avoidance, leading to risk-averse target setting that hinders performance.

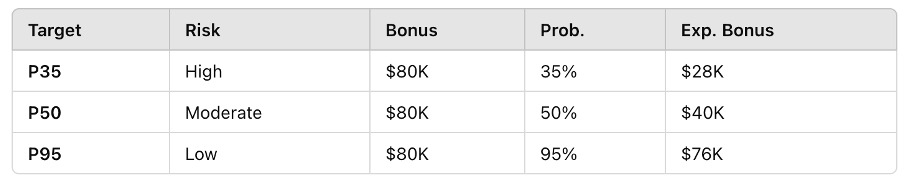

When difficulty is not factored into target setting, reaching a target that triggers, for example, a bonus of $80 thousand does not mean that the expected bonus is $80K.

For example, a P35, P50, or P95 target represents a 35%, 50%, or 95% chance of meeting or exceeding the goal, with the nominal $80 thousand bonus’s expected value ranging from $28 thousand to $76 thousand (Table 1).

Table 1.

In other words, the real incentive to go for the high-risk P35 option would be almost 65% less than going for the low-risk P95 option.

Ignoring difficulty in target setting incentivizes managers to argue for easier targets to maximize their bonuses. In fact, two-thirds of managers would recommend setting easily attainable goals rather than striving for ambitious targets, resulting in a bias toward cost reductions at the expense of long-term growth.

Even when stretch targets are set, ignoring the difficulty level prevents accurate performance evaluation. For instance, a $100 million P35 target can have an expected value of $95 million, but reaching it is perceived as ‘underperformance.’

Similarly, a P95 target of $100 million can have an expected value of $110 million, which is celebrated as ‘overperformance’ when, in fact, the level of execution in both cases is exactly the same.

Ironically, underperformance, such as $105 million in the P95 scenario, might be mistakenly celebrated as ‘overperformance,’ while overperformance, such as $97 million in the P35 scenario, could be viewed as ‘underperformance.’

Disclaimer: In reality, it is not possible to draw such conclusions from single outcomes, which is explored more here. However, the point still stands, as companies often operate in such ways regardless.

The Solution

Assuming Buffett and Munger were right, and since incentives are typically tied to reaching targets, a company’s target setting may dictate up to 99% of people’s behavior, regardless of how it affects company performance.

According to Richard Rumelt, goals are decisions about what is important and should therefore result from working through challenging problems, not serve as antecedents.

Additionally, as McKinsey notes, “unless there is a sense of shared ownership for the fortunes of the company, you will have a hard time getting the full commitment of your team to the big moves required to mobilize your business.”

Therefore, to incentivize behaviors that drive company performance, executives must ensure that making the best decisions for the company is aligned with achieving set targets.

Executives can do this by setting targets that address critical challenges and opportunities, are dynamic to stay relevant over time, account for the impacts of business decisions to eliminate short-term suboptimization, and incorporate probabilities to reflect difficulty and the influence of luck—accounting for risk-taking while avoiding rewards or penalties for dumb luck.

Address Critical Challenges and Opportunities

Instead of arbitrary, psychologically satisfying numbers, such as $1 billion, or rules of thumb, such as +10%, executives should base targets on understanding critical challenges and opportunities.

At the company level, this means integrating target setting into strategy formulation.

If a company is struggling to grow, it should ask: what makes growth difficult? For example, already high market share in a declining market. The company should also identify key opportunities, such as new sustainable product segment growing by 20% to 30%.

To address challenges and seize opportunities, the company should revise its strategy (e.g., expanding into sustainable product segment) and set targets that align with these choices, such as $100 million in sustainable product sales.

Suppose last year’s sales were $900 million. The ‘reality of the situation’ may be that reaching $850 million in legacy product sales, within a declining market and under increasing regulatory requirements, is already a realistic and challenging target.

Therefore, instead of $1 billion, or $990 million, a realistic and challenging target for the full year would be $950 million, which includes defending legacy sales and adding $100 million in sustainable product sales.

The difference between this and a generic $1 billion or +10% target is that the number is based on real-world assumptions, not the other way around.

This enables debating, testing, and revising the targets when the assumptions change—in other words, basing the targets on reality. This is explored further in here.

Of course, companies also use real-world assumptions to ‘justify’ arbitrary numbers.

Then, however, real-world factors often become tools in political power games, with the goal of negotiating as large a buffer as possible to the static target, rather than genuinely understanding the business situation.

While a skilled negotiator may thrive in companies where targets are based on static numbers as a result of political negotiations, a company will perform better as a whole when targets are based on critical real-world challenges and opportunities.

Set Dynamic Targets That Remain Valid Over Time

To be effective, targets need to remain valid over time. Rather than static figures, companies should set dynamic targets that remain realistic and challenging across various future scenarios, especially those beyond their control.

According to BCG, companies should replace static targets with flexible ones and use external benchmarks like market share, return on capital employed, or relative total shareholder return to create more adaptable and accurate performance measures.

Consider the earlier example of $950 million in sales. Instead of setting a target to increase sustainable product sales to $100 million and maintaining legacy sales at $850 million, the company could aim to capture a sustainable segment market share of 5% and preserve market share in legacy products.

This shifts the target from static to dynamic—where sales volumes fluctuate with market changes—and from absolute to relative, measuring performance against the competition.

Additionally, according to McKinsey, macroeconomic factors such as inflation and exchange rates should be automatically adjusted, regularly reviewed and communicated across the organization to ensure alignment at all levels.

For example, assume the company’s strategy is viable when sustainable products cost 10% more to produce, with cost targets based on a 2% inflation rate.

Rather than setting a fixed cost target, like $100 million or $100 per pound, the company should automatically adjust for inflation. For instance, a $100 million target based on 2% inflation would adjust to $103 million under 5% inflation.

While inflation can often justify price increases, this approach works well in many scenarios. However, when it doesn’t, the company must assess at what point profitability becomes unsustainable.

At that stage, the company may need to revise its strategic choices, rather than relying on operations to further reduce costs, as all reasonable cost reductions should always be in place, regardless of inflation.

Account For the Impacts of Business Decisions

Jack Welch wrote, Anyone can manage for the short-term, and anyone can manage for the long-term, but the mark of a leader is to have the rigor and courage to do both simultaneously.

According to a BDO survey, companies should align incentives with their strategies by adjusting short-term incentives to account for economic conditions and prioritizing long-term incentives to promote sustained growth.

To eliminate sub-optimization (read: cheating), targets must cover decision impacts. This may require setting targets three to four years out.

Teams should have an extended period of time to reach these targets, which allows them to focus on continuous improvement and long-term value creation rather than short-term target achievement.

This also means tying bonuses to longer term projections instead of annual measures, which is harder to do but less prone to manipulation.

When managers regularly make decisions that (1) have long-term impacts and (2) involve both short- and long-term trade-offs, true performance can only be measured with metrics that account for the impacts of both.

Consider the earlier example of a company switching focus from legacy products to sustainable ones. Instead of setting targets for only the next year, executives making decisions four years out should have targets that extend that far into the future.

Instead of targeting a 5% segment share for sustainable products, they should set targets to reach, for example, 5%, 10%, 14%, and 18% in years 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Further, instead of setting four bonus measures for the first year only, companies should distribute the bonuses over four years, and continue the same practice in subsequent years.

This way, an executive who starts this year is eligible for only 25% of the total bonus in year 1 and for the full 100% only after four years (Picture 1).

Picture 1.

The key difference from traditional target setting is that this approach better captures the real impact of executives’ decisions. The timeline, whether two, four, or six years, depends on the situation. The point is that the calendar year is not the ‘one size fits all’ solution it’s often assumed to be.

This may seem less agile, but it isn’t. Agility depends on decision lifecycles, not the frequency of target revisions. In any case, executives make decisions with impacts that span several years. Aligning targets to those has little to no negative impact on agility, but it improves executives’ accountability for those decisions.

Of course, not all individuals make decisions that affect performance several years into the future. Therefore, a logical conclusion is to set targets with different time horizons for different levels of the organization.

While top executives, whose strategic decisions have multi-year impacts, must have targets that create ‘skin in the game’ for several years, lower-level operational roles, where decision impacts last weeks or months, should have targets set for shorter periods and revised more frequently.

This also increases the clarity of decision rights, which not only improves accountability and commitment but also enhances decision quality and speed.

There are a few key reasons why executives might oppose such a system. First, they may not consider a partial bonus in the first year ‘fair.’

In reality, the opposite is true. It’s not ‘fair’ to fully reward an executive who makes decisions with multi-year impacts based solely on one year’s performance.

First, most of the decisions affecting that year were made by someone else years ago. Second, it’s impossible to determine how much of the results stem from ‘cheating’ (e.g., moving sales from next year to this year) versus sustainable actions that enhance long-term performance.

Some will object, believing this will lead to too many measures. They may already have five to ten measures for the current year, and extending those to four years out would quadruple the number of targets, making none of them meaningful.

While this may be true, many measures are often needed because they aren’t based on a critical challenge or opportunity. When they are, a small number—perhaps only one—is enough, as the criteria for the issue or opportunity ensure overall performance improves.

Finally, the most common concern is that setting long-term targets seems impossible, but this is often a self-imposed issue. Static numbers can’t stay relevant far into the future, which is why targets should be dynamic to adapt to changing factors outside executives’ control, such as market dynamics.

While it won’t eliminate uncertainty, dynamic targets make outcomes more dependent on performance than on luck. Remaining uncertainty from difficulty and luck should be managed by incorporating probabilities.

Set Probabilistic Targets

According to McKinsey, “Organizations that invest in low-probability, high-payoff projects are more likely to outperform competition on revenue growth and return on capital.”

Whether explicitly stated or not, all targets have an inherent level of difficulty and reaching them is influenced by luck. Therefore, to incentivize risk-taking, companies should use probabilistic targets.

In fact, as McKinsey puts it, to be able to determine afterward whether the result was due to poor performance or poor luck, companies must be explicit about whether a plan is a P30, P50, or P95 (the exact numbers not being the point).

Instead of setting deterministic targets, such as achieving a 18% market share, executives should assign probabilities based on underlying assumptions.

For example, reaching a 18% market share may depend on several factors: an 80% probability that R&D will develop sustainable products with functionality comparable to legacy products, an 80% probability that sales will acquire the necessary customers once the product is ready, and an 80% probability that operations will keep cost increases below 10%, as cost management depends on both product characteristics and sales volume.

Therefore, the probability of reaching a 18% market share is approximately 50% (80% × 80% × 80%), making it a P50 target.

Disclaimer: This is a simplified example. In practice, estimating the probabilities involves more complexity and interdependencies between factors.

Being able to address these factors is critical when setting targets for longer-term. Executives might worry, “What if we miss the first-year targets? Then targets for years 2, 3, and 4 will become impossible to achieve.”

Well, that may be the case, but at the same time, they’ve been making decisions that impact the four years. If those decisions don’t result in expected performance, why should they be rewarded with bonuses?

“Something unexpected might happen.” That’s certainly a possibility, but if the targets are dynamic, they remain valid in many such scenarios.

And the inherent remaining uncertainty is addressed with probabilities. For example, the target for year 1 may be P95, for year 2 P80, for year 3 P65 and for year 4 P50 (Picture 2.). By definition, missing some targets is expected, but rewards are also higher when they are reached.

Picture 2.

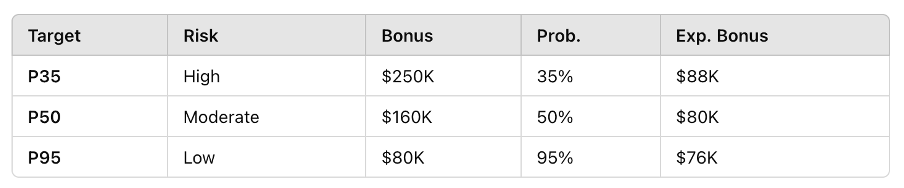

Consequently, achieving a P35, P50, or P95 target should be rewarded differently.

Think, for example, of gymnastics. Athletes’ performance is judged by summing the score for the difficulty of the routine and the score for the quality of the execution.

Similarly, in business, hitting a P35 target should have a higher reward than hitting a P50 target, and a P50 target should have a higher reward than hitting a P95 target (Table 2).

Table 2.

In our earlier example (Table 1), even if the expected value were the same ($76K) for both P35 and P95 targets, meaning that in the long run the company would not pay more for P35, the incentive to choose it would be almost 200% higher than if the probabilities were not accounted for.

An astute reader might think this could lead to even more gaming, as it creates an incentive to lie about the probability to inflate the bonus. And this can lead to absurdly high bonuses because it is difficult to evaluate the real probabilities.

This is certainly a possibility, though not a necessity, when certain factors are considered.

First, setting probabilistic targets is more difficult than traditional methods. It’s not recommended to jump from a traditional approach to three-times-higher bonuses for P35 targets overnight.

It’s the same as not recommending that someone who is obese and out of shape start running 5 miles, 5 times a week, even though it is arguably highly beneficial for overall health and well-being.

Second, to be useful, probabilities need to be based on real-world assumptions and continuously revised with a planning system capable of learning from multiple outcomes over time, which can make probabilistic targets reduce possibilities for gaming, as explored further here.

Therefore, before applying probabilities to targets, companies must become ‘fluent’ with assumptions and probabilities in decision-making. This means focusing on the assumptions, instead of the numbers, focusing on ‘improving the odds to win’ and changing the characteristics of a company’s planning systems.

From Killing Growth to Incentivizing It

Traditional target setting has major flaws that incentivize behaviors that may kill growth. It is often based on absolute figures resulting from political negotiations rather than on realistic and challenging goals.

Even if initially sensible, these targets often become disconnected from reality and unworthy of pursuit as underlying assumptions change. At the very least, they fail to account for a significant part of decision impacts, making it possible to ‘cheat’ to reach them at the expense of future performance.

In addition, they typically don’t address inherent uncertainty or the influence of luck, incentivizing risk-averse target setting and ironically leading to celebrating underperformance as overperformance, and vice versa.

Despite these flaws, traditional target setting has two major advantages. First, it doesn’t require any change. Second, it doesn’t measure true performance (yes, you read that right).

While ‘that’s what we’ve always done’ is the worst reason to do anything, it does have the advantage of requiring no time or resources to change the way of working.

This is a significant benefit, as changing target setting affects people’s power and bonuses. The efforts to overcome the ‘social side’ of the change are considerable, even if we assume the technical aspects are easily understood and learned—which they likely aren’t.

So, while the benefits can be substantial, the difficulty of such a change is likely high, which may make the expected value not worth the risk. Even if it were, the likelihood of failure—and its fallout—may be too high for the risk tolerance of most.

This doesn’t account for the fact that the status quo is likely better for some. The fact that traditional target setting doesn’t measure real performance creates additional ‘tools’ to reach targets, collect bonuses, and appear to be a high performer.

There is more room to tell compelling stories that are not based on reality, with less accountability for those stories (e.g., what really happens in the next three to four years), since ‘it’s impossible to set targets that far.’

No one is necessarily the wiser, even if a large part of long-term growth was, in fact, killed by short-term cost cuts that offset poor performance (or simply poor luck) in the short term to hit a maximally incentivized static budget figure that didn’t make sense to hit in the first place.

When target setting is deterministic and only loosely based on real-world factors, the odds are there will be ‘surprises’ like the weather, competition, or the economy that can be cited as the reason for yet another ‘hair on the hairy back,’ just like every other year in the past five years.

This is not to suggest that most companies are incapable of working in a better way.

It is only to point out that even if these principles would likely lead to better performance for the entire company in the long term, those benefits must be evaluated in the context that the change itself is much harder than the technical aspects—and not all individuals will come out better off after such changes.

Similarly, while a strong case can be made that the free-market system leads to better performance for countries, it may not be feasible for a communist country to implement such a system. And even if it were, not all individuals who are well off in the communist system would fare as well in the free-market system, which is why they would strenuously resist such change.

It can be difficult to overcome that resistance because setting dynamic targets that account for decision impacts requires focusing on improving the ‘odds to win,’ as considering longer-term impacts effectively requires a holistic view of performance and the use of probabilities.

Practical insights

- Poor target setting may be the root cause killing growth.

- Base targets on critical challenges and opportunities, instead of +10%.

- Set dynamic and relative targets that remain valid over time.

- Include short- and long-term decision impacts in the targets.

- Account for the difficulty and influence of luck with probabilities.