Introduction

Over 70 years of research shows that if Strategic Planning (SP) were a medicine, in three out of four cases, it would either have no effect or make the condition worse.

Yet, surveys of managers’ and executives’ beliefs show they overestimate its impact on financial metrics by a factor of at least three and as great as six.

In most companies, the Annual Budgeting Process (ABP) is a joke, and everyone knows it. It “takes an inordinate amount of work for no obvious purpose” other than helping senior executives to command and control.

As Michael C. Jensen and Jack Welch have written, it wastes time and encourages managers to lie, cheat, lowball targets, and inflate results. It penalizes honesty, turning business decisions into gaming exercises that hinder growth.

According to McKinsey’s research on 1,600 companies over 15 years, for a third of them, next year’s budget is essentially the same as last year’s budget.

Moreover, how often does the budget become obsolete before the ink dries, causing the company to question the months spent creating it? How often does SP produce a lengthy PowerPoint full of incoherent activities that the company never acts on?

As Kaplan and Norton put it: “Typically, such plans then sit on executives’ bookshelves for the next 12 months.”

At best, SP and ABP have no impact on decisions; at worst, they are actively harmful. This is because they focus on creating static plans rather than making decisions.

As a result, plans become disconnected from real business decisions, and obsessing over ‘hitting the plan’ conflicts with making the best decisions. The good news is that this disconnection is entirely a result of how the company is managed—not VUCA or the inherent uselessness of planning—and can therefore be fixed.

The Problem

Executives struggling with growth often blame poor execution or poor forecasting for not ‘hitting the plan.’ However, they fail to recognize that their plans, targets, planning processes, and worldviews are likely flawed from the start and the real root causes of poor performance.

In business, a plan is a coordinated set of decisions aimed at achieving specific targets based on specific assumptions.

Plans become ‘actively harmful’ for four key reasons: they are valid only under specific assumptions, the characteristics of the planning processes that create them misalign with the characteristics of real decisions, the targets the plans aim to achieve are poorly set, and the worldviews that created those planning systems and targets assume the world is deterministic, when in reality it’s probabilistic—meaning outcomes are shaped by uncertainty and luck, and the impacts of which are ignored or misunderstood.

Plans Are Valid Only Under Specific Assumptions

As Rita McGrath wrote, “Even the best companies can run into serious trouble if they don’t recognize the assumptions buried in their plans.”

Assumptions are real-world factors that may or may not materialize. For example, the market could rise or fall by a certain amount. While it’s impossible to predict outcomes with certainty, decisions inherently rely on assumptions—whether explicitly stated or not.

For instance, an Annual Operating Plan (AOP) may include decisions to develop new products and raise prices, assuming the sustainable products segment will grow by 25% and raw material prices will rise by 5%

The plan also includes assumptions about the impacts of these decisions: new products will increase sales by $100 million, and price increases by $50 million. The plan, including the impacts, is valid if the sustainable products segment and raw material prices grow as expected, but not if both remain unchanged.

As Mike Tyson put it, Everybody has a plan, until they get punched in the face.

Executives are often reluctant to make assumptions explicit because they cannot be sure what they are. However, they fail to understand that there is no ‘not assuming.’ Making assumptions is like breathing; everyone does it.

Failing to make assumptions explicit increases the likelihood that stakeholders will operate under different assumptions, leading to misalignment that hinders performance, regardless of how the assumptions play out.

For example, the product team might expect the sustainable product segment to grow by 25% anticipating $100 million in sales, while the sales team assumes 10% growth, expecting only $70 million in sales.

Regardless of market growth, this misalignment hinders performance, causing the company to either waste R&D resources or fall short in selling and delivering new products.

Failure to align across functions is often cited as the biggest obstacle to strategy execution, with only 9% of managers saying they can reliably depend on other functions.

Even when stakeholders agree on the assumptions in the plans, they are often disconnected from reality. This disconnect occurs because the ‘plan creation’ processes tend to be more about political negotiations than a genuine effort to understand what is happening in the business.

Lower levels aim for lower targets to increase their chances of exceeding goals and maximizing bonuses, while top of the company pushes for higher targets to drive maximum effort and build a buffer for the inherent uncertainty.

Additionally, according to McKinsey, since most projections are created by finance teams disconnected from the business, these numbers often include built-in biases, inconsistencies, mistakes, and missing components.

These disconnections are rarely addressed properly, as focusing on creating static plans is antithetical to learning: it lacks the creation of hypotheses and the careful generation of tests, and it fails to question the underlying assumptions.

The root cause of many of these problems stems from the characteristics of the planning processes themselves, as they misalign with real decisions and lack a feedback loop from real data.

Planning Processes’ Characteristics Misalign with Decisions

According to a survey, organizations that run annual planning processes make only 2.5 major strategic decisions a year, and often do so despite their planning processes rather than because of them.

Targets and plans become disconnected from reality when the characteristics of planning processes used to create them are not aligned with business decisions.

Common planning processes like SP and ABP are typically calendar-driven, while most decisions are made continuously —over dinner, in the shower, or during meetings with key stakeholders.

As Roger Martin has said, “People have nutty corporate tendencies to do strategy in ‘September,’ and if I were truly bloody-minded and wanted to stomp all over a competitor, I would attack them the day after the board has approved the strategy.”

Typically, the cadence and time horizons of calendar-driven planning processes do not align with the frequency and impacts of real business decisions.

For example, the ABP has an annual cadence and a 12-month time horizon, which makes it suited for decisions that can be made once a year in the fall and have impacts limited to a calendar year.

Try listing real business decisions that fit these criteria—you might find it difficult.

A low planning cadence either significantly decreases agility or disconnects plans from real business decisions.

Consider the decision to launch new products. It may take 1 to 2 months to make the decision, after which it takes 6 to 12 months to develop the product, after which it remains in the portfolio generating revenue for 3 to 4 years. In other words, it has a decision lifecycle of 4 to 5 years.

An annual cadence (if used to make real decisions) can extend decision-making time by 6 to 12 times, execution time by 100% to 200%, and the overall decision lifecycle by 20% to 25%, significantly delaying the renewal of the entire product portfolio.

Moreover, artificial time horizons encourage gaming and sub-optimization, as many decision impacts fall outside the planning scope.

Since costs occur upfront while revenues come later, the planning process’s 12-month time horizon creates a cost bias in decision-making, often leading to short-term cost cuts at the expense of long-term growth.

Finally, ‘plan creation’ processes like SP and ABP represent single-loop learning, whereas genuine learning includes an additional step: reflecting on assumptions and testing hypotheses.

In other words, these processes lack a crucial component of strategic learning: gathering feedback, testing hypotheses, and making necessary adjustments.

According to Mankins and Steele, less than 15% of companies track performance against their strategic plans, which may explain why many continue funding losing strategies rather than changing course.

In fact, in many companies, “performance monitoring amounts to little more than reporting the weather.” Fixated on static numbers, they obsess over “How did we perform?” instead of asking the more critical question: “Should we alter course?”

The root cause for this, and for the characteristics of the planning processes, often lies in how companies set targets, as poorly set targets not only fail to require such planning systems but also drive behaviors that render these systems ineffective and unnecessary.

Targets Are Poorly Set

Charles Munger and Warren Buffett used to say: “95 percent of behavior is driven by personal or collective incentives”, only to later correct themselves: “95 percent was wrong; it is more like 99” (as cited in Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick).

Executives often set ambitious targets based on hope rather than reality, relying on rules of thumb, such as a 10% increase, psychologically satisfying numbers like $1 billion, or political compromises.

Richard Rumelt calls such targets as “Dilbert-style corporate management” since they are disconnected from “the reality of the situation”, meaning they are arbitrarily set instead of based on an understanding of critical challenges and opportunities.

Even when targets are initially based on reality, the level of difficulty is influenced by luck. The most important targets are often static figures, but they rarely remain realistic and challenging over time because the assumptions behind them inevitably change.

Bjarte Bogsnes illustrates the absurdity of static absolute targets with a football team aiming to score 45 goals next season. Similarly, sales of $1 billion might not reflect good performance in every scenario.

For example, while a sales target of $950 million may be realistic and challenging in a flat market, as assumed in the budget, it would require 3% higher performance if the market declined by 3% and would allow for 3% lower performance if the market grew by 3%—equivalent to nearly $30 million higher or lower sales.

Put differently, static targets have a dynamic level of difficulty.

The fact that targets are often not initially based on reality—and even if they are, they rarely remain so over time—creates an incentive to lowball them and lie about what is really happening in the business.

These behaviors are exacerbated by tying static targets to annual bonuses, as is often the case. This, at the very least, ensures that targets become disconnected from reality.

Because of this, like planning in general, target setting is often more a political negotiation than a genuine attempt to determine what is good for the business as a whole in the long-term.

Additionally, targets set for a calendar year often ignore the multi-year impacts of major decisions, leading to cheating and a misalignment between achieving targets and maximizing performance.

That’s why marketing costs are the first to be cut when profit targets are at risk: costs are short-term, but revenues are longer-term. When targets ignore long-term growth, short-term profits can be artificially inflated to hit the targets.

However, as Kaplan and Norton argue, “meeting short-term financial targets should not constitute satisfactory performance when other measures indicate that the long-term strategy is either not working or not being implemented well.”

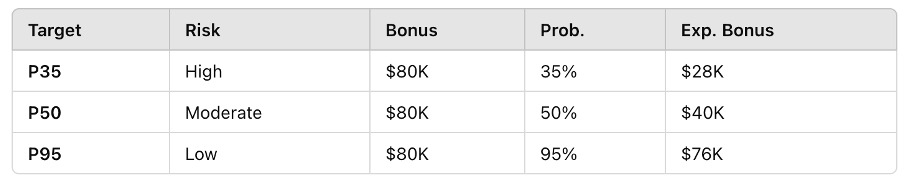

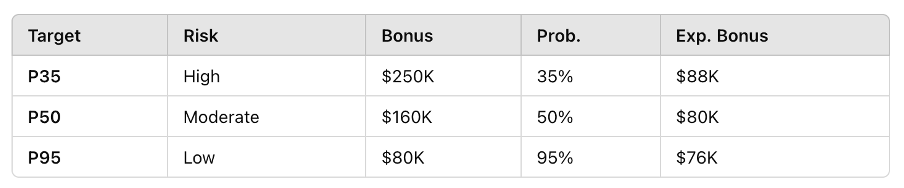

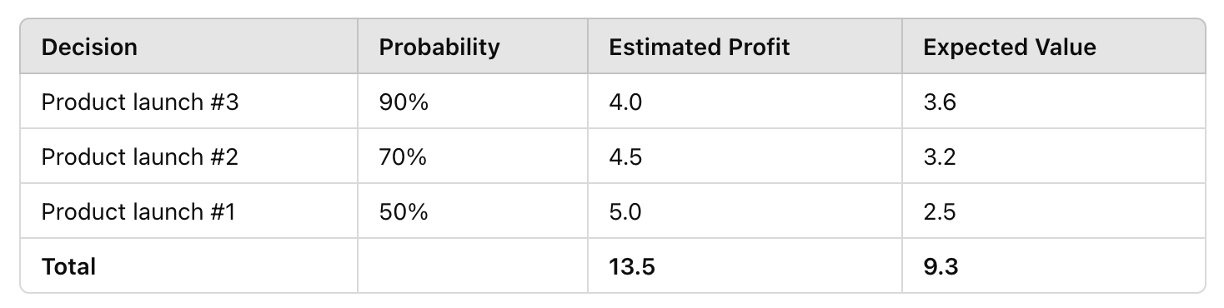

Finally, like all decisions, targets are probabilistic, but this is rarely addressed in target setting. Depending on whether the targets are P35, P50, or P95, there can be a 35%, 50%, or 95% chance of reaching or exceeding the target.

As a result, for example, with a nominal bonus of $80 thousand, its expected value may vary from $28 thousand to $76 thousand (Table 1).

Table 1.

On one hand, executives expect risk-taking; on the other, they not only often fail to reward it—but, in fact, discourage it. This disconnect leads to risk-averse targets, which will hinder performance.

Even when stretch targets are set, ignoring probabilities prevents accurate performance evaluation. This can ironically even lead to situations where underperformance is celebrated as overperformance, as explained here.

The root cause for poor target setting is acting as if the world is deterministic.

The World Is Probabilistic, Not Deterministic

Jeff Bezos wrote to Amazon shareholders in 2016: “Given a 10 percent chance of a 100 times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten.”

While exaggerated for effect, the same principle applies to all decisions. Without probabilistic thinking, executives are unable to make bets with the highest expected values; instead, they play it safe, which “is the most dangerous thing in the world.”

The root cause of the misalignment between planning processes and business decisions is executives’ flawed view of the world: they act as if it’s deterministic, when in fact, it’s probabilistic—shaped by uncertainty and luck.

However, the unpredictability of the future, as demonstrated by Edward Lorenz, is a fundamental characteristic of the real world—something that no amount of budget revisions, better forecasts, or improved ‘execution’ can overcome.

The key misconception is treating business decision-making like a game of chess, where objectively ‘right decisions’ exist, and success depends solely on the player’s effort and skill.

In reality, business is more like poker: there are no ‘right decisions,’ and outcomes involve an element of luck that skill or effort cannot eliminate.

Yet many executives fail to acknowledge the role of luck or understand how to leverage it by considering assumptions and their probabilities.

Instead, they evaluate decisions based on outcomes: a $1 million profit is seen as a good decision, while a $1 million loss is viewed as a bad one.

This is known as ‘resulting’ or ‘outcome bias,’ which Cassie Kozyrkov calls “the most important concept in decision analysis” and “one of society’s favorite forms of mass irrationality.”

While it may seem like common sense to judge the quality of a decision based on its outcome, the two are different.

In reality, outcomes are probabilistic, meaning that a decision to launch new products could have, for example, a 10% probability of losing more than $1 million, a 20% probability of an outcome between a $1 million loss and a $1 million profit, and a 70% probability of earning a profit greater than $1 million.

The probabilities depend on the assumptions. For instance, there might be a 10% chance the market drops by more than 5%, a 20% chance it fluctuates between -5% and +5%, and a 70% chance it grows by more than 5%

This means that, as Annie Duke points out, learning in probabilistic environments is not trivial, as they “by definition respond every time differently to the same input.”

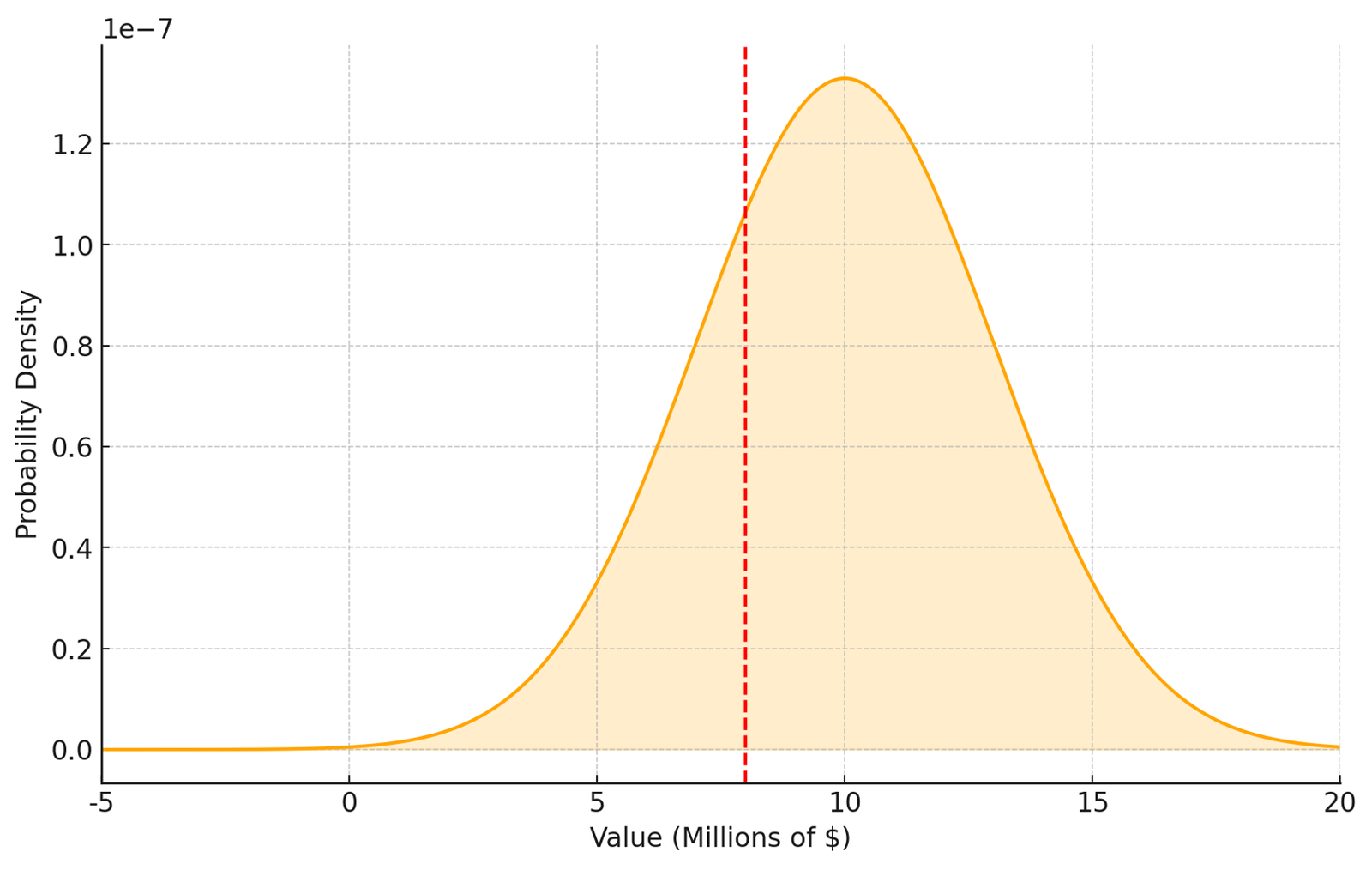

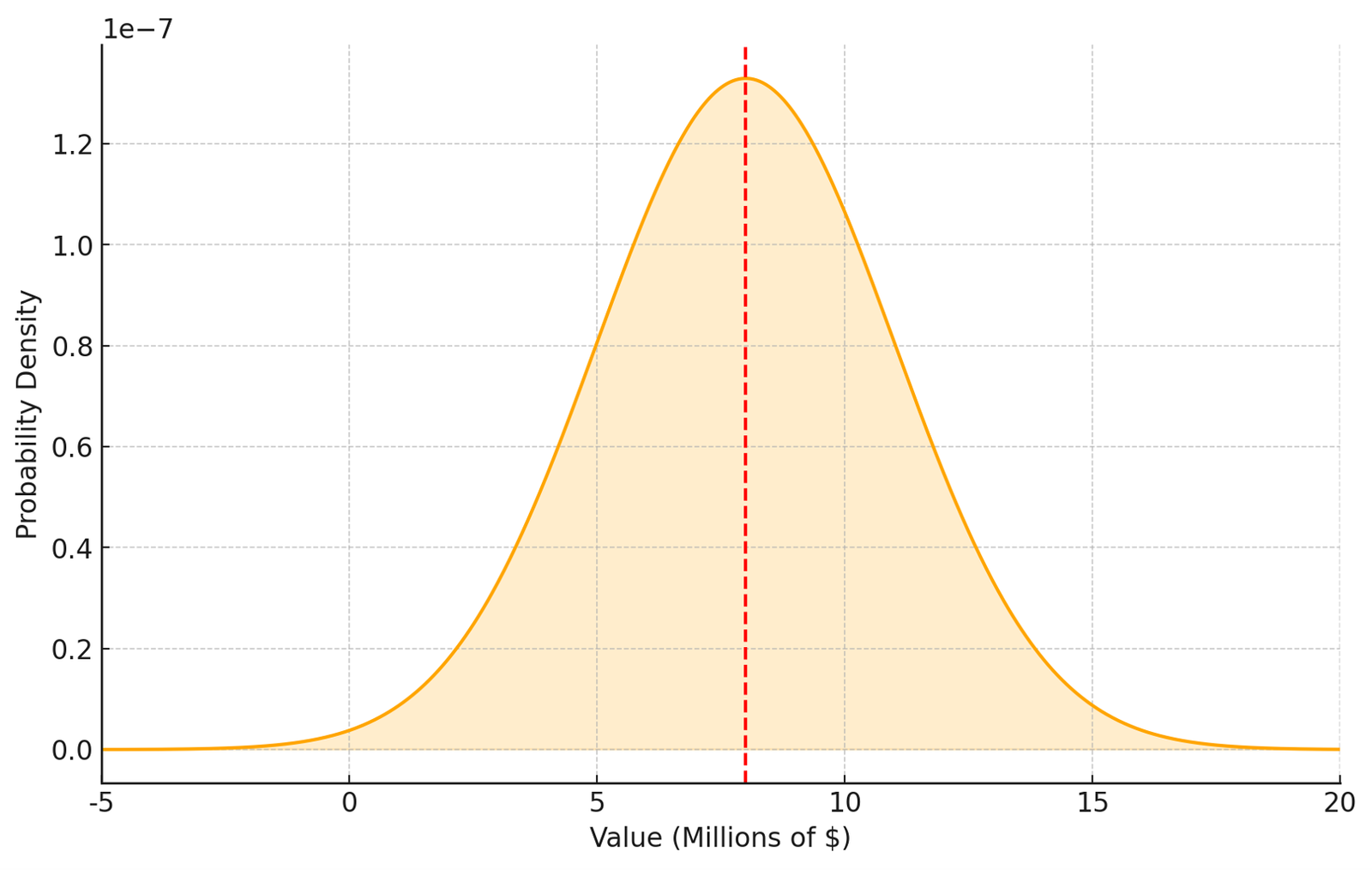

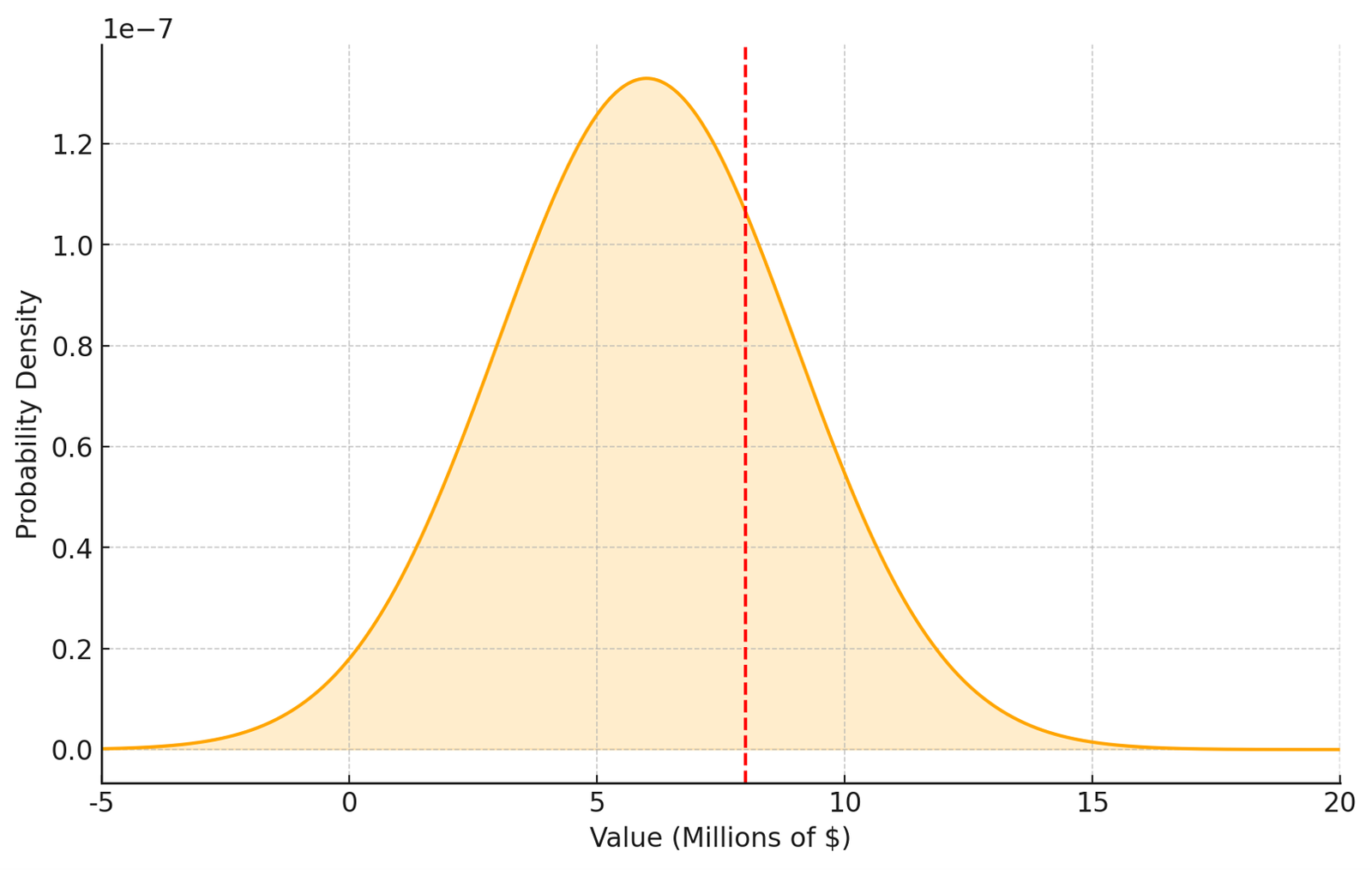

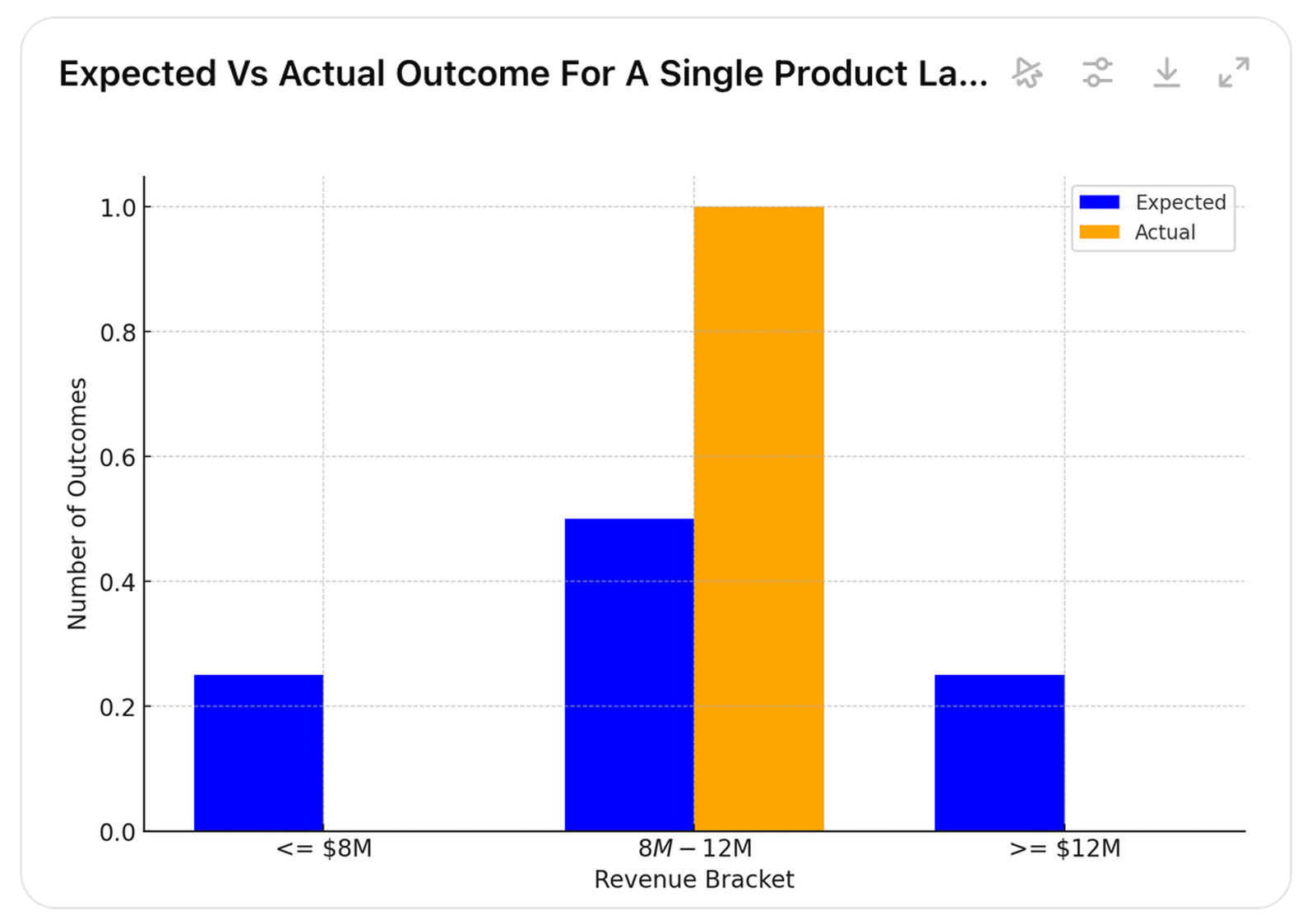

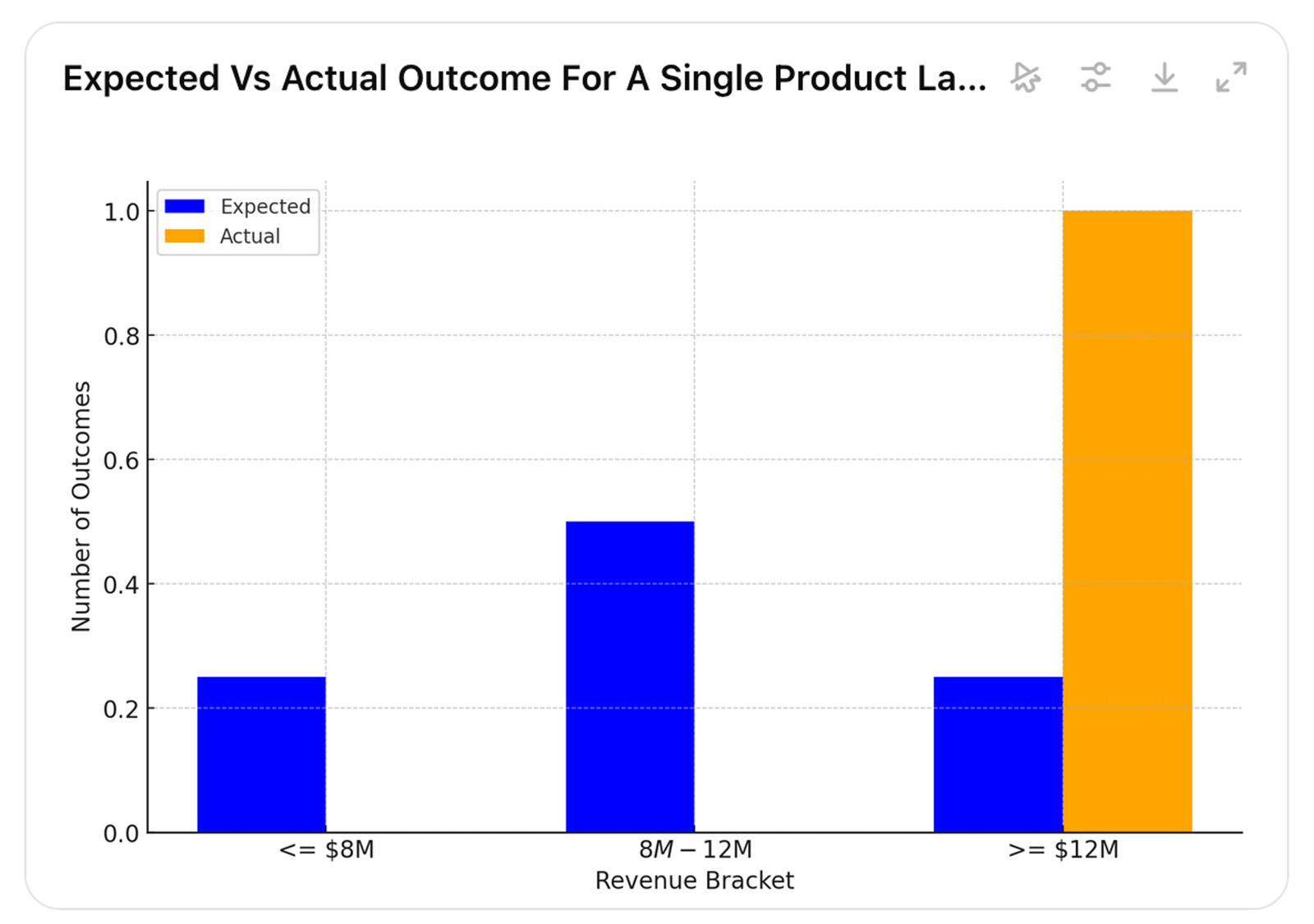

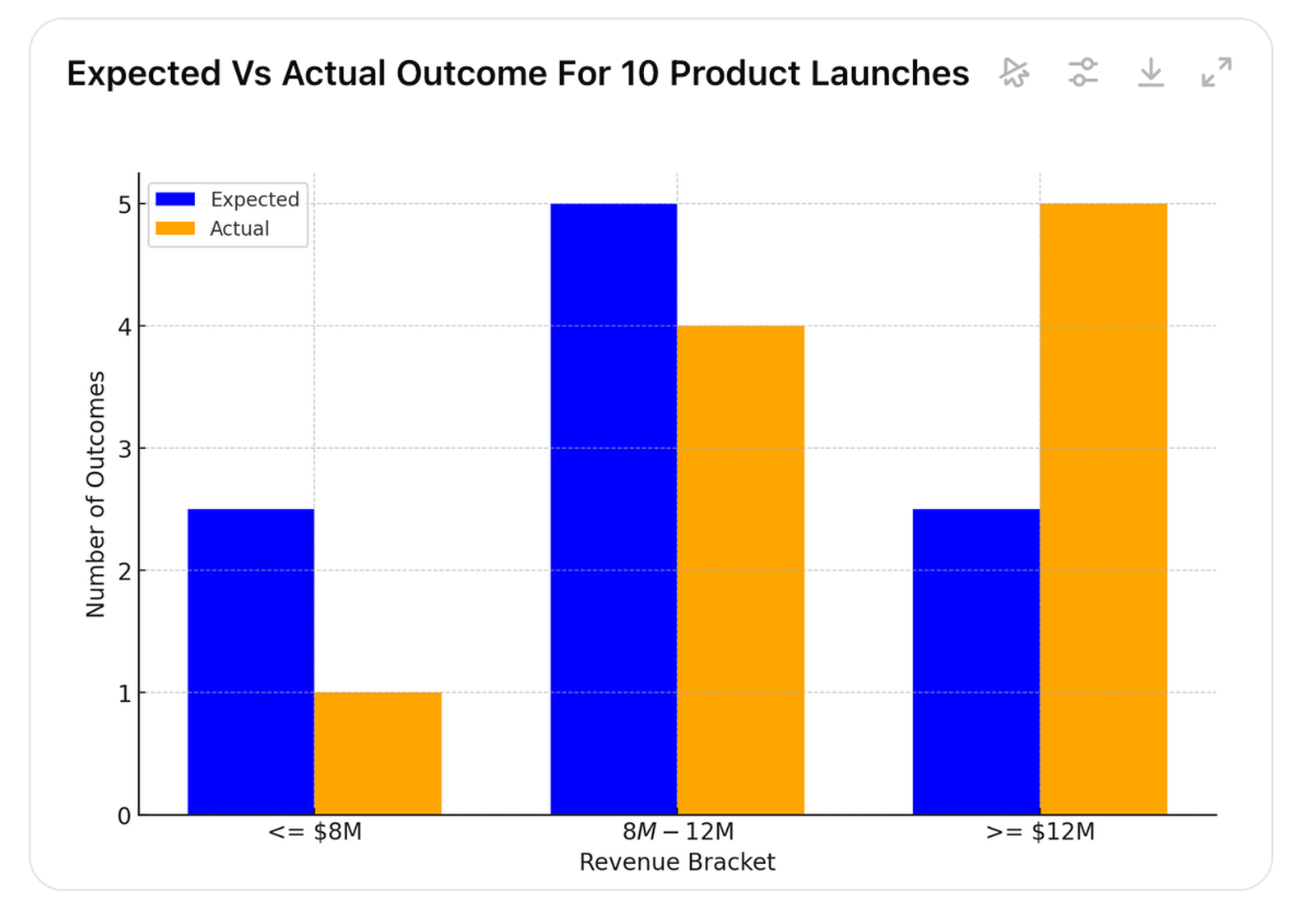

For instance, an $8 million sale could result from a probability distribution with an expected value of $10 million, $8 million, $6 million, or any number of other possibilities (Pictures 1 to 3).

Picture 1.

Picture 2.

Picture 3.

Based on a single outcome, it’s impossible to determine which, making it impossible to conclude how much luck influenced that outcome.

Explaining the reasoning in depth is beyond this article’s scope. However, the logic applies equally when we’re making decisions in the real world, just as it is with scientific and statistical questions.

A flawed view of the world, coupled with the ‘non-triviality of learning,’ leads to, at best, ineffective, and at worst, actively harmful ‘performance management.’

This happens when executives focus on improving individual outcomes rather than overall performance, which comes in several forms.

The most basic form is opting for the ‘safe bet.’ Consider the Bezos quote: if there were a second option with a 90% chance for a 2x payoff, its expected value would be 1.8x, while the riskier bet with a 10% chance for a 100x payoff has an expected value of 10x.

At the company level, this manifests as dividing the company into numerous deterministic silos across business units, functions and time periods, where ‘hitting the plan’ means those individual parts hitting their short-term targets, rather than the company having the best chance of hitting a holistic objectives in the long term.

While companies often have such holistic targets, they ignore that maximizing the whole requires more than optimizing its parts. In other words, obsessing over numerous deterministic short-term targets not only fails to deliver the best possible holistic performance, particularly in the long-term, but is likely counterproductive.

Finally, as described in more detail here, due to their deterministic nature, companies’ performance management may resemble searching for messages in TV static, as they don’t recognize that actual values are often distorted by meaningless noise.

When those actuals are compared to a budget that no longer reflects reality—as decisions and assumptions have changed—companies draw conclusions from the gap between what expected performance shouldn’t have been and what the actual performance wasn’t.

Indeed, the real world is probabilistic, yet executives’ mindsets—and therefore their planning systems—are deterministic, making their targets and plans flawed from the start. As a result, they are often unable to determine whether poor performance is due to flawed decisions, poor execution, both, or neither.

This leads to holding on to bad decisions when they should be revised, revising decisions when execution should be improved, and assigning blame when no one is at fault, which results in rewarding dumb luck and punishing ‘noble failures.’

The Solution

Bain & Company’s 2020 research of 3,713 companies found that focusing on high performance has 35 times more impact on total shareholder return than aiming for accurate quarterly earnings predictions.

Effective planning must therefore be a continuous, iterative process that produces better decisions, rather than a periodic ‘plan creation’ process that results in static plans, which quickly become obsolete and hinder performance.

While planning involves creating plans, the key difference is that in effective planning, plans are merely tools to improve the chances that decisions will have better outcomes over time. In contrast, in ‘plan creation,’ the plans and their static numbers become ends in themselves.

As partners from Bain and Co bottom-lined it, “Ultimately, a company’s value is the sum of the decisions it makes and executes.” And research shows that decision effectiveness correlates with financial results with over 95% confidence across industries and company sizes.

To shift focus from plan creation to making better decisions, companies must focus on the assumptions, not the numbers; align planning cadence and time horizons with decisions; set dynamic targets that account for decision impacts; and focus on improving the ‘odds to win.’

Focus on the Assumptions, Not the Numbers

According to Rita McGrath, “Companies can learn to spot when they’re making unconscious assumptions.”

Companies need to shift focus from the numbers in the plans to the assumptions behind the numbers. These assumptions need to be clearly documented, because otherwise, as Ackoff, Martin and Kozyrkov have argued, people are prone to hindsight bias—forgetting what the original assumptions were, or adjusting them to fit whatever happened afterward.

A good place to start documenting assumptions is the list of reasons for underperformance.

For example, if the company expected $100 million in sales from new sustainable products but actual sales were $80 million, and the stated reason is that segment growth fell short of expectations, the company must make explicit what is assumed about future segment growth.

Documenting assumptions will enable stakeholders to debate them, align expectations, test them against real-world events, and learn from the findings to revise decisions.

Consider the earlier example where the product team expects $100 million in sales from new sustainable products, anticipating segment growth of 25%, while the sales team predicts only $70 million because they expect lower 10% segment growth.

Instead of debating whether the sales will be $70 million or $100 million, or debating after the fact what the assumptions behind those numbers were, the question should be ‘what would have to be true,’ for the sales to be $70 million or $100 million?

This shifts the focus to real-world factors, and the future that can be influenced, rather than static figures or who is ‘right’—neither of which improve performance.

The conclusion could be that to reach $100 million sales, the sustainable product segment would have to grow 25%, and consumers would need to accept 10% price increases: two real-life factors that can be tested and learned from.

Rather than treating either assumption as a static fact, the company should test them in practice, beginning with the one stakeholders are least confident in. For example, the company could test the price sensitivity with pilot products or markets.

Instead of getting stuck with the static outcome of $100 million, the company should update the assumptions, and the impacts to outcomes, based on actual data.

It could turn out that the customers are willing to accept even higher +15% price increases which would lead to $105 million sales, but on the other hand the market growth could be only 10%, indicating only $90 million sales.

Continuously revising future assumptions enhances the company’s ability to predict outcomes, recognize performance gaps early, and make necessary decisions sooner—ultimately improving performance.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover these topics in detail, but they are discussed further here.

To focus on assumptions rather than numbers, companies must align their planning systems with real business decisions; otherwise, they won’t be able to understand the full impact of those decisions or update plans when assumptions change.

Align the Characteristics of Planning Processes with Decisions

According to McKinsey research, having the right process is six times more important than analysis in improving revenue growth and profitability.

Executives must recognize that decision-making is not a one-time event but a process that unfolds over time. As BCG partners put it, “planning cannot be a one-time thing. It needs to be an all-the-time thing,” which, as Ed Barrows characterizes, is “a more realistic approach than the once-a-year planning meeting that still dominates many corporate planning efforts.”

In practice, all-the-time doesn’t mean ‘all the time’; it means a regular cadence. Just as being in the gym all the time would be overkill, and going only from April to July wouldn’t be sufficient, finding the right cadence, like four times a week, is the key.

The right cadence depends on the typical decision lifecycles—how long it takes to make, execute, and commit to a decision. Ideally, the cadence is at least 20 times shorter.

This is because the decision lifecycle determines agility. A cadence less than 20 times the typical decision lifecycle causes only a negligible decrease in agility—on average 2.5%, and at worst, 5%.

For example, tactical decisions like launching new products, which involve multi-year commitments, require at least a bi-monthly cadence. Operational decisions with shorter commitments, such as deciding which SKUs to stock, need a minimum weekly cadence. Conversely, the annual cadence that most companies use is best suited to decisions with lifecycles of 20 years or more.

Additionally, the planning time-horizon should reflect decision impacts, rather than arbitrary periods like the calendar year or what seems ‘relatively predictable,’ such as the next six months.

This is because, regardless of predictability, executives influence the company’s future over the time-horizon their decisions impact.

For instance, if the decision to launch new products affects the company’s future 4 to 5 years out, the planning time-horizon should reflect that. Regardless of what happens, a significant portion of the company’s product portfolio will consist of sustainable products, influencing its costs and ability to generate revenue.

Furthermore, because companies make different types of decisions, aligning cadence and time-horizon requires implementing multiple planning processes.

For example, one for strategic decisions with a quarterly cadence and a rolling 5- to 10-year time-horizon, one for tactical resource allocation decisions with a monthly cadence and a rolling 3- to 4-year time-horizon and one for operational decisions with a weekly cadence and a rolling 20- to 30-week time-horizon.

Finally, the most critical characteristic of any planning process is having a feedback loop from actual data, which tests the validity of assumptions and the quality of decisions in the plans, leading to continuous revisions of the plans.

This means the planning processes used to create and revise plans must also serve as performance measurement systems that track actuals against the plans.

When even one of these conditions is not met—if the planning process isn’t continuous, its cadence and time-horizon don’t align with real decisions, or it lacks a feedback loop for continuous revisions—the process will produce plans disconnected from reality, while real decisions are made elsewhere.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover these topics in detail, but they are discussed further here.

To align their planning processes with real decisions, companies must set dynamic targets that account for decision impacts; otherwise, these processes will produce plans aimed at targets that undermine long-term growth.

Set Dynamic Targets That Account for Decision Impacts

Assuming Buffett and Munger were right, and since incentives are typically tied to reaching targets, a company’s target setting may dictate up to 99% of people’s behavior, regardless of whether it maximizes the company’s performance.

To align individual success with company performance, executives must set dynamic targets that account for decision impacts, address critical challenges, and consider the level of difficulty and the role of luck.

A key challenge for a $900 million company struggling with growth may be its high market share in a declining market, while the sustainable product segment, growing 20% to 30% annually, offers a significant opportunity.

Therefore, instead of setting a target of $1 billion or $990 million (+10%), a realistic and challenging target could be $950 million, consisting of $850 million in legacy product sales and $100 million in new sustainable product sales.

However, to be effective, the target needs to remain realistic and challenging across various possible future scenarios, particularly those beyond the company’s control.

Rather than targeting $950 million, the company could aim to capture a 5% share of the sustainable segment while maintaining its legacy product market share.

Although market share has its limitations and may not always be ideal, it is dynamic: the required dollar amount for strong performance increases in a growing market and decreases in a declining one.

In addition, targets must account majority of decision impacts to eliminate sub-optimization (read: cheating), typically for the short-term.

As Jack Welch has written, Anyone can manage for the short-term, and anyone can manage for the long-term, but the mark of a leader is to have the rigor and courage to do both simultaneously.

Since managers regularly make decisions that (1) have long-term impacts and (2) involve both short- and long-term trade-offs, true performance can only be measured with metrics that include the impacts of both.

This may require setting targets three to four years out.

Instead of targeting a 5% segment share for sustainable products, they should set targets to reach, for example, 5%, 10%, 14%, and 18% over the next four years, with bonuses tied to those milestones.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to explore the reasoning or numerous counterarguments for this, the most common being ‘it’s impossible to set targets that far out,’ which, in fact, is a self-imposed issue.

Indeed, it’s impossible to set static numbers that will remain relevant far into the future. This is why targets should be dynamic—so they stay relevant when factors outside executives’ control, like market dynamics, change.

While this won’t eliminate uncertainty, it will increase the likelihood that hitting or missing the targets is more due to performance and less due to luck. The remaining inherent uncertainty, due to difficulty and the influence of luck, should be addressed by incorporating probabilities.

According to McKinsey, to be able to determine afterward whether the result was due to poor performance or poor luck, companies must be explicit about whether a plan is a P30, P50, or P95 (the exact numbers not being the point).

Instead of setting deterministic targets, such as achieving a 18% market share, executives should assign probabilities based on underlying assumptions.

For example, reaching a 18% market share may depend on several factors: an 80% probability that R&D will develop sustainable products with functionality comparable to legacy products, an 80% probability that sales will acquire the necessary customers once the product is ready, and an 80% probability that operations will keep cost increases below 10%, as cost management depends on both product characteristics and sales volume.

Therefore, the probability of reaching a 18% market share is approximately 50% (80% × 80% × 80%), making it a P50 target.

Disclaimer: This is a simplified example. In practice, estimating the probabilities involves more complexity and interdependencies between factors.

Consequently, achieving a P35, P50, or P95 target should be rewarded differently.

Think, for example, of gymnastics. Athletes’ performance is judged by summing the score for the difficulty of the routine and the score for the quality of the execution.

Similarly, in business, hitting a P35 target should have a higher reward than hitting a P50 target, and a P50 target should have a higher reward than hitting a P95 target (Table 2).

Table 2.

An astute reader might think this could lead to even more gaming, as it creates an incentive to lie about the probability to inflate the bonus. While possible, also the opposite can be true, and even more likely, as discussed here.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover these topics in detail, but they are discussed further here.

To set dynamic targets that account for decision impacts, companies must focus on improving the ‘odds to win,’ as considering longer-term impacts effectively requires a holistic view of performance and the use of probabilities.

Improve the ‘Odds to Win’

As Annie Duke put it: “Making better decisions starts with understanding this: uncertainty can work a lot of mischief.”

According to McKinsey, probability-weighted, scenario-based forecasts produce the most reliable results, and investing in low-probability, high-payoff projects correlates with organizations outperforming their competitors on revenue growth.

To be effective, planning must focus on improving the odds that decisions will ‘win’ by learning and adapting, rather than predicting the unpredictable and obsessing over ‘hitting the plan.’

Research shows that the ability to think probabilistically and change one’s mind in the face of new information determines how well one can predict the future.

The factor that best distinguishes superforecasters from others is that they believe estimating probabilities of real-world events are a skill that can be learned.

As Philip Tetlock wrote: “Foresight isn’t a mysterious gift bestowed at birth. It is the product of particular ways of thinking, of gathering information, of updating beliefs. These habits of thought can be learned by any intelligent, thoughtful, determined person.”

Here’s a simple test by Tom Chivers. Imagine a cancer test that is 99% accurate: it correctly identifies 99% who have cancer and correctly identifies 99% who don’t have cancer. Despite that, 99% of people it says have cancer don’t.

If you can explain why, you may be literate in probabilistic thinking. If not, understanding is likely your issue, and you might need to study the basics.

While it’s essential to have some basic knowledge, it is far more important to start using probabilities in practice. As the old saying goes, “It’s easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting.”

A practical place to start is by making explicit the probabilities of the business outcomes one wants to improve, such as month-end results or new product launches.

Instead of stating outcomes as a single figure, such as $10 million, one should use probabilities that cover all possible outcomes.

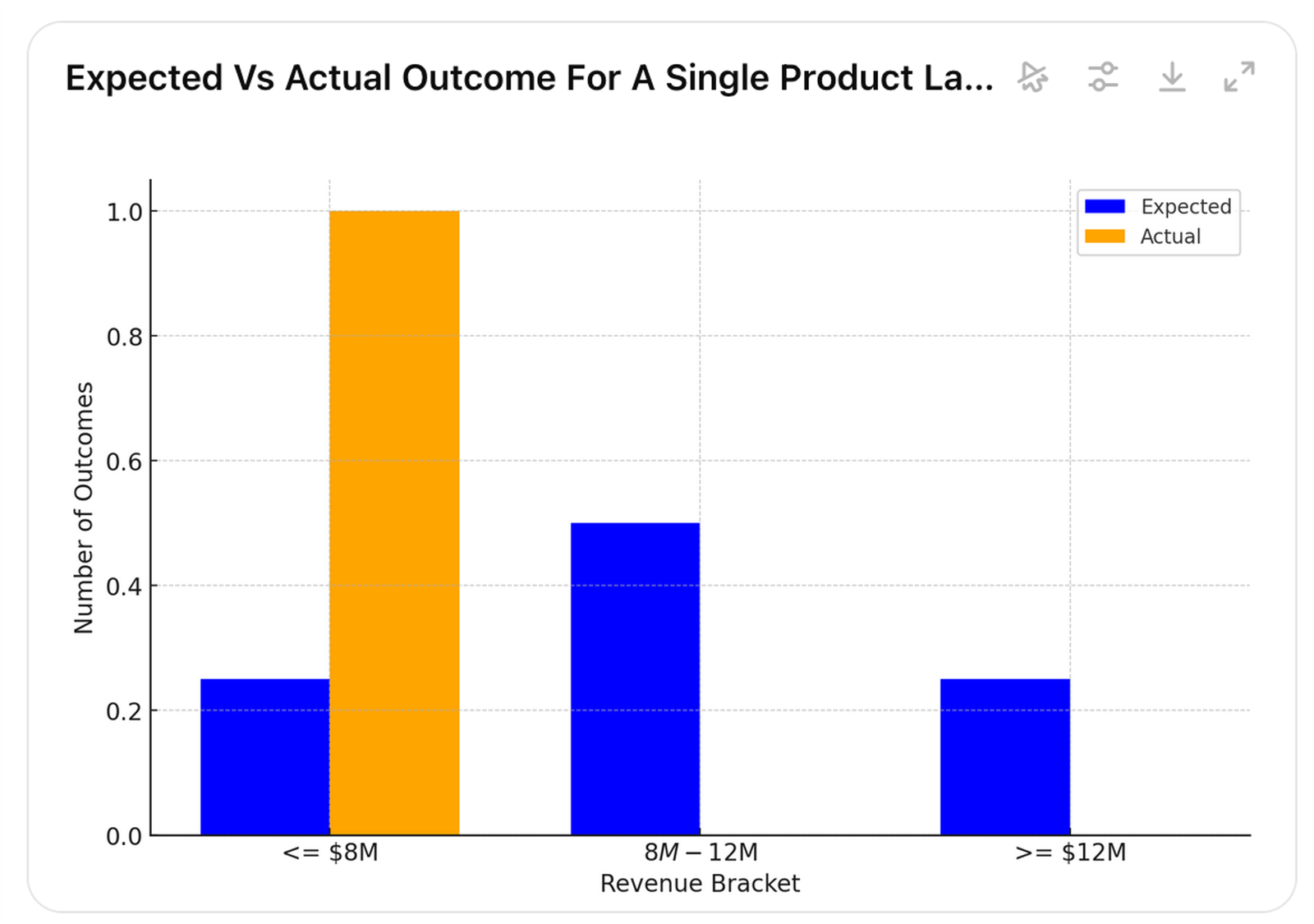

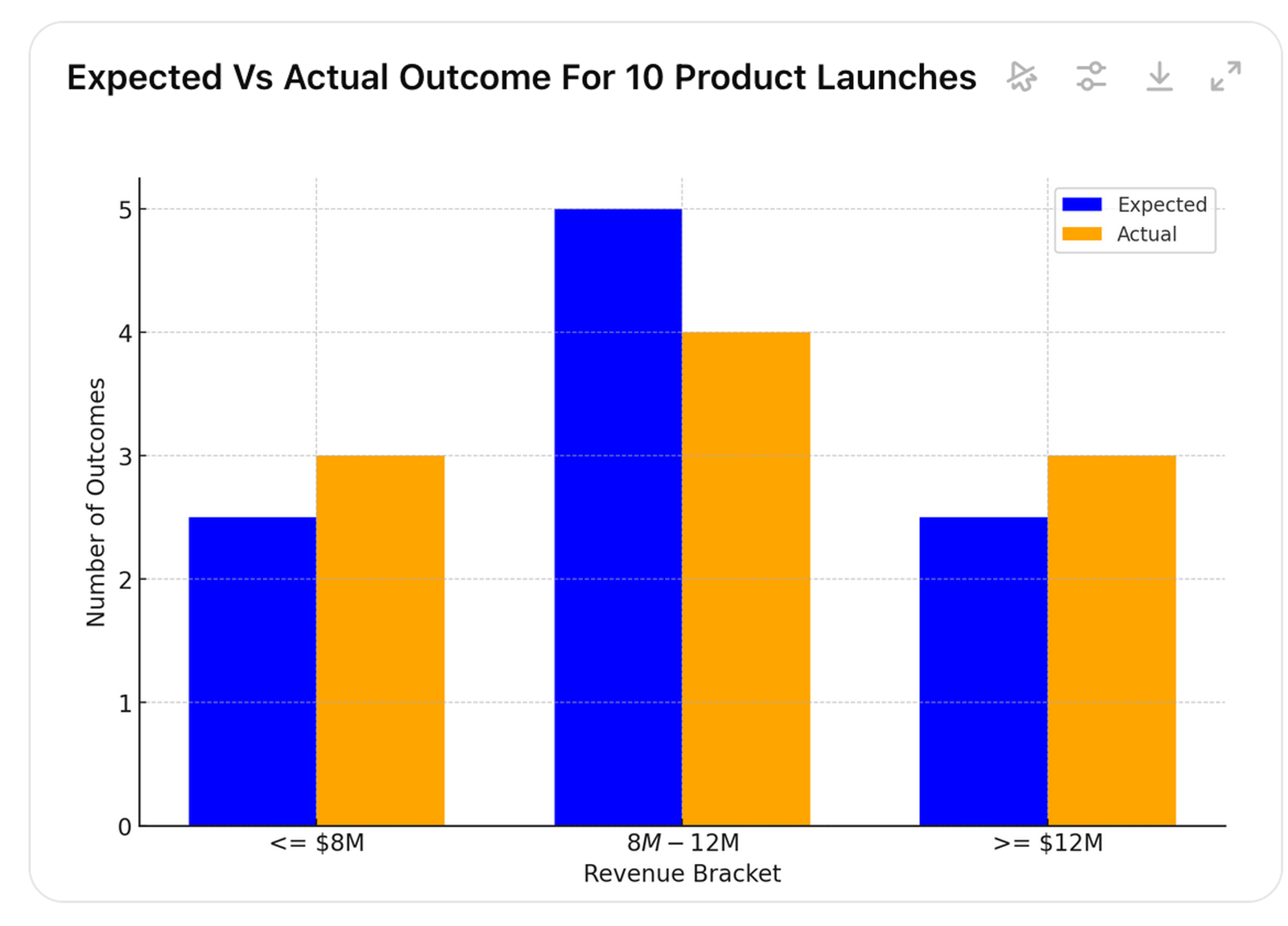

For instance, there may be a 25% probability that sales will be $8 million or less, a 50% probability that sales will be between $8 million and $12 million, and a 25% probability that sales will be $12 million or more.

Similarly, instead of stating that the assumption of future segment growth is 25%, one could say there is a 50% probability that the segment growth will be 20% to 30%, a 25% probability that it will be less than 20%, and a 25% probability that it will be more than 30%.

There is a simple two-step formula to determine the probabilities. First, determine the base rate (outside view). Second, revise that based on specific differences in your situation compared to the outside view.

For example, sustainable products in other markets may have grown 15% to 25% in 50% of markets, less than 15% in 25% of markets, and more than 25% in 25% of markets—this is your base rate.

You adjust the growth rates higher based on the added information that, in your specific market, the government is passing stricter restrictions on legacy products than in other markets, which will lead to the probabilities described earlier.

To understand how well actuals align with estimates, companies should focus on learning from multiple outcomes over time. It’s an essential criterion if one is serious about improving predicting the future.

Consider earlier example with sustainable products. Regardless of the probabilities, after one product launch, the actual value could fall into any of the estimated probability brackets (pictures 4 to 6).

Picture 4.

Picture 5.

Picture 6.

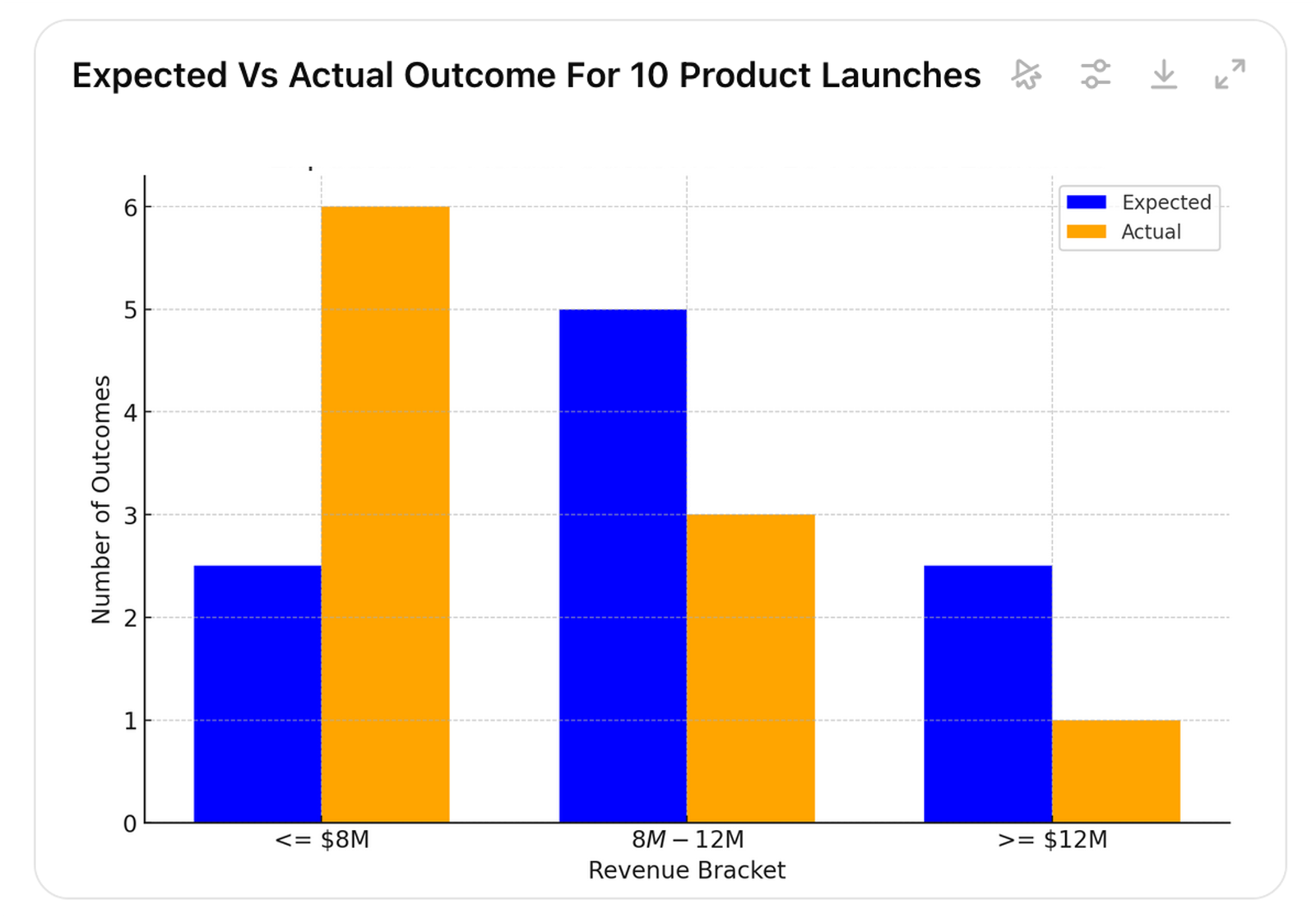

However, after multiple product launches, we are likely to see one of the patterns in pictures 7, 8, or 9 (it is of course also possible that all brackets would be equally likely or the extremes would be more likely than the middle).

Picture 7.

Picture 8.

Picture 9.

Picture 7 indicates that the estimated outcome is overconfident, as lower actual values occur more frequently than expected. In picture 8, actual values occur roughly as often as expected, and in picture 9, higher values occur more often than expected, indicating that the expectation is underconfident.

Whether or not executives consider probabilities in their decision-making, a company’s long-term profits are the cumulative result of the expected values of all decisions, plus luck. And the longer the time-horizon, the smaller the impact of luck.

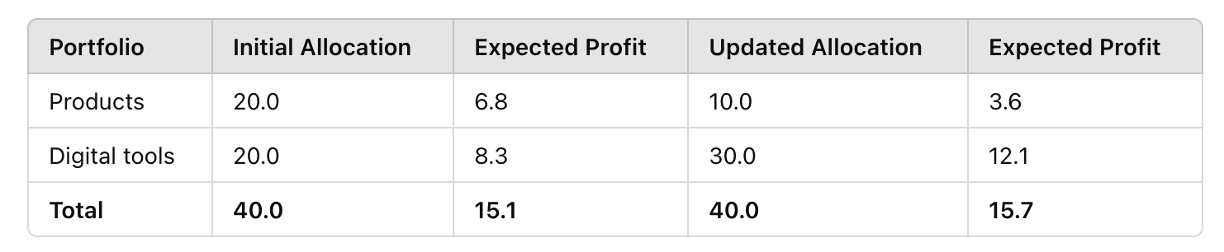

Rather than describing decision outcomes as single deterministic figures and focusing on being ‘right,’ executives should frame outcomes as a combination of probability and utility, prioritizing those with the highest expected value (Table 3).

Table 3.

At a company level, this means allocating resources to those business units, functions or initiatives that improve the expected value of the total. For example, re-allocating $10 million from product launches to digital investments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Moreover, although short-term outcomes are typically more certain than long-term outcomes (think, for example, cutting marketing costs), companies can improve their ‘odds to win’ by reallocating resources in a way that increases expected value over time (Table 5).

Table 5.

With traditional thinking, one would never take a bet with only a 10% chance of success. Even if they did, after failing a few times, they would likely stop and stick with bets where the payoff is low but probable and achievable in the short-term.

With probabilistic thinking, one could take the 10% chance of a 100x payoff every time, even if it meant being ‘wrong’ 9 times out of 10.

A common misconception about being ‘long-term oriented’ is that it means neglecting the short term. In reality, it’s the opposite. While ‘short-term orientation’ does indeed typically neglect the long term, focusing on the long term simply means not neglecting it, or put differently, it means accounting for ‘all the terms.’

It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover these topics in detail, but they are discussed further here.

Plans are Useless – Planning is Indispensable

Despite running annual planning processes like the ABP and SP, most companies also engage in continuous planning, for example, in monthly leadership meetings, month-end budget reviews, or weekly team meetings, to respond to changing assumptions and unexpected outcomes.

How else would the marketing costs get cut so often, despite what’s in the budget?

This raises an important question: If the executives continuously evaluate the real situation and make decisions based on changing factors, and already have a good understanding of the business on the relevant time horizon, “why engage in a slow, painful planning exercise when you’re not even going to follow the plan?”

A more effective approach is to establish continuous planning processes that align with decision impacts, regularly evaluate the latest situation based on real-life factors (the assumptions), pursue dynamic targets that remain relevant, and focus on improving the odds that decisions will ‘win’ over time.

In other words, as Eisenhower put it, Plans are useless—planning is indispensable.

Practical insights

- Change the output of planning from static plans to better decisions.

- Set dynamic targets that cover decision impacts, instead of annual +10%.

- Focus on the assumptions behind the decisions, instead of static numbers.

- Align planning cadence and time-horizon with decisions.

- Improve the ‘odds to win’ rather than obsess over ‘hitting’ obsolete plans.