The Problem

Those rolling out (no bun intended) rolling forecasting processes often notice that not all cross-functional stakeholders are eager to ‘be on board’ with the program.

Although the title (along with many people implementing such approaches) picks on sales, you could just as easily replace sales with any other cross-functional stakeholder.

Sales are the ‘usual suspects’ because sales (both the function and the outcome) play a critical role in forecasting, and it’s difficult to have an effective planning process without forecasts.

Yet executives aiming to implement rolling planning processes often end up wondering: “Why aren’t the sales on board?”

It seems odd, right?

After all, the logic of rolling forecasting is simple and straightforward: the world is constantly changing, and the company needs to understand where it’s going to make the right decisions continuously.

What’s so hard to be ‘on board’ with that?

Executives pondering this may find themselves asking:

“Don’t they get it?

“Don’t they understand what’s good for them?”

“Don’t they care about how the company is doing?”

How frustrating!

The Reason Why Sales Aren’t ‘On Board’

While the factors mentioned above might play a role in rare individual cases (and while the initial problem might be that they don’t ‘get it’), the odds are that in most situations, these are not the reasons why sales (or anybody else) eventually isn’t ‘on board.’

In fact, it’s the exact opposite. It’s because they do (eventually) ‘get it,’ and certainly understand what’s ‘good for them,’ that they aren’t ‘on board.’

The real issue? For them, it’s simply not worth being on board.

It’s not that they wouldn’t care about how the company is doing either. They do, but they also care more about how the program affects them personally (as most people would).

Put differently, it’s not that sales doesn’t care about the rolling forecast or its benefits. Instead, executives implementing these processes send a clear message—without necessarily realizing it—that sales shouldn’t care, or that they should care more about something else, often something contradictory.

Three key issues drive this misalignment:

- No Accountability: There’s little accountability for what happens in the rolling forecast process—neither for the content going in nor the outcomes coming out.

- Misaligned Incentives: Incentives tied to rolling forecasting are either weak or nonexistent compared to more powerful, often conflicting, incentives.

- Change in Power: In the ‘old way,’ they might have had significantly more influence over some decisions, such as products or production. With the ‘new way,’ some of that power is gone.

When the question is reframed as, “Why aren’t sales acting against their own incentives and accountabilities and willing to relinquish their power?” the answer becomes obvious.

That’s a silly question.

As the MythBusters used to say: “Well, there’s your problem.”

Executives wondering why sales isn’t engaged need to look in the mirror. They are implementing a system that requires behavioral change without addressing the incentives or accountabilities driving those behaviors and changes the power of the stakeholders without managing those repercussions.

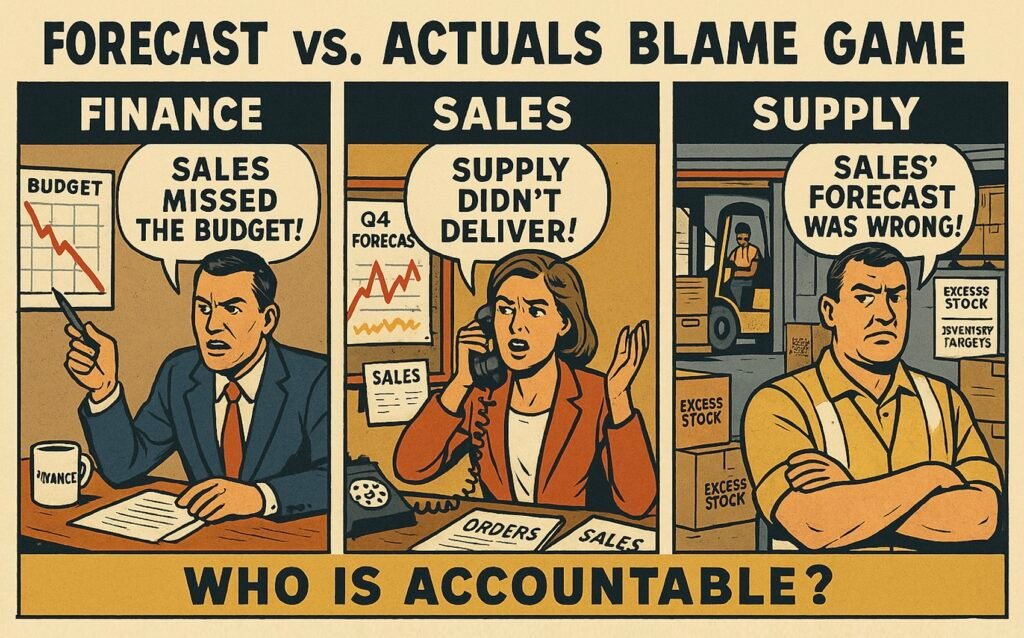

No Accountability

The simplest reason why any stakeholder group, such as sales, is not ‘on board’ with the rolling forecasting process (or any planning process) is that they have no real accountability for its inputs or outcomes.

It’s like wondering why the CEO isn’t excited about the new mail cart in the mailroom: she isn’t responsible for delivering the internal mail.

No, the point isn’t to equate rolling forecasting to delivering mail. It’s simply that people naturally care less about things outside their purview.

Sure, the CEO cares whether the mail gets delivered, but she likely cares far more about achieving the performance targets she is responsible for. The same principle applies to sales and their level of interest in the new rolling forecasting process.

Reasons to implement it may include:

- Provide more frequent visibility (monthly or quarterly) into how the business is performing.

- Extend the planning horizon, such as looking 12 or 18 months ahead.

And after implementing a rolling forecast, executives may wonder why sales isn’t updating their projections for the year, quarter, or month despite the new ‘more effective’ process.

They also don’t understand why sales isn’t generating new ideas that drive growth next year or engaging in substantive discussions about it. Instead, they see half-hearted projections, illogical initiatives, technical mistakes, and an overall lack of effort in what is presented for the next year.

In other words: “Why isn’t sales on board?”

Could it be that, regardless of the new process, they have no accountability of the updated monthly estimation (what it is, or whether it realizes), nor what happens past the calendar year?

They have accountability to deliver figures for the calendar year that were set in stone 6, 7, 8 or how many months ago.

“What if the situation has gotten worse?”

Well, it may have been worse already 3 or 5 months ago, but nobody listened to them then either-so why would they now? And if the lower ‘reality’ is reflected in the rolling forecast, what happens?

Appraisals and rewards for being honest and truthful?

Or do they get the toilet brush, increased micromanagement to get to the bottom of the problem, and mounting pressure to implement whatever short-term suboptimization is necessary to ‘hit the plan,’ even if it undermines the longer-term aspirations the rolling forecast process was meant to support?

“What if the situation is better? Shouldn’t we prepare?”

Yes, you should. However, if sales ‘surprises’ with more demand, accountability for delivering on that demand falls to someone else. Sales is prepared on its part and is likely to hit and exceed bonus targets, possibly even maximizing them.

Why, then, are you asking sales to take accountability for others’ readiness, or to deliver more than they are incentivized to provide?

Often, not only is there no accountability of what happens as a consequence, but even the accountability to produce the forecast (or plans), is not with the stakeholder group that has ‘natural business accountability.’

For example, the accountability about what will be sold (forecast) or what decisions and assumptions (the plan) it is based on, is not with sales, but with finance or operations.

Put differently, a group of people who have no business accountability of what will be sold, are making plans and forecasts about what will be sold, while executives wonder, why doesn’t the stakeholder with business accountability (for example sales), feel accountable of those plans and forecasts (that are made by someone else).

It’s the same as asking the marketing team to design a new product without input from the engineering team and then wondering why the engineers don’t feel accountable for the product’s performance.

Misaligned Incentives

As a corollary to not having accountability for what goes into rolling forecasting or happens as a consequence, sales (or any stakeholder group) typically has existing contradictory incentives to what rolling forecasting is trying to accomplish.

For example, sales incentives typically focus on delivering the budget, set annually and often split into quarters and months. The pressure is to hit static targets determined months ago, on a shrinking time horizon, whether or not those targets still make sense.

In fact, if they deliver more than expected, it will likely result in higher static targets for the next year. Despite the ‘rolling forecasting,’ the reality remains that targets are still set annually, one calendar year at a time.

In other words, you’re asking them to accept lower bonuses or higher risks for no clear benefit. And if there is any flexibility in targets, which way is that likely to go?

If sales is 100% truthful and transparent about all opportunities, is it more likely that the targets for the year (without additional compensation) will go up or down?

The effect is the same: the risk of failing to achieve bonuses—or at least being reprimanded—rises. And for what benefit? The company may or may not perform better?

How about the lack of interest in the long term?

Could it be that whether sales executives can renovate their kitchen or take their family on holiday depends entirely on hitting arbitrary numbers for this year—while whatever appears in the rolling forecast for next year has absolutely no impact on their performance evaluation, let alone their bank account?

If next year’s forecast appears overly cautious, with few significant opportunities, or overly optimistic, with little risk, could it be because the negotiations over what needs to be accomplished—and next year’s vacation money—have yet to take place?

At the very least, there is a strong incentive to align forecasts with whatever position benefits those negotiations: maximizing resources with overly optimistic forecasts or minimizing sales targets with overly pessimistic projections.

What’s the incentive to tell the truth? And more broadly, where is the accountability for the story being told?

Unless you can answer those questions, these are the reasons why sales isn’t ‘on board.’ And even if you come up with an answer, the odds are it pales in comparison to the incentives driving the behavior you’re observing.

Here’s a simple test: Write down the biggest incentive and accountability (concretely, not vaguely) for sales (or whichever cross-functional stakeholder group isn’t ‘on board’).

Next, write down the biggest incentive and accountability for the behavior you’d like to see (for example, avoiding surprises this year or focusing on how to grow in the long-term).

Unless the incentives and accountability for the desired behaviors are at least equal to—and preferably much higher than—those driving current behaviors, “well, there’s your problem.”

Change in Power

To have an impact on performance, the rolling forecast process needs to change the way decisions have been made. This is likely to change the power dynamics of the stakeholders.

When incentives and accountabilities are not aligned with new intended behaviors, the odds are that changes in the power dynamics are also not properly managed.

For example, in the absence of a formal cross-functional planning process, sales often achieve their goals through personal relationships—for instance, with key stakeholders in product management or supply chain.

Even with the best intentions, and even if it could be soundly ‘proven’ that the new way is ‘more effective,’ the reality is that a reduction in sales’ influence over product or inventory decisions may be the real reason they don’t see the point in ‘getting on board.’ They are already on board with the people they need. If they need a product, they call Mike in R&D; if they need inventory, they call Jane in production.

However objectively better it might be for the company to shift these decisions to a holistic cross-functional process, that doesn’t change the fact that sales would lose some of their personal influence, making it harder for them to ‘hit the plan.’

In addition, they may have had more ‘artistic freedoms’ in the story they tell about how the future looks, and that story may differ between finance and operations.

For finance, the story might be more conservative, to ensure sales is more likely to exceed it, while for operations, it might be more optimistic, to ensure enough is delivered to meet their actual needs.

The reason they do either is the same: it serves their self-interest.

They know from experience that whenever they fall short of financial estimations, they’ll get reprimanded. Similarly, if there is no buffer in the forecast to operations, they often end up missing products for customers, failing to meet their sales targets, and once again, getting reprimanded.

So, it’s not that they don’t ‘get’ that the new approach is better for the company—they do. But they also understand that it may be worse for them personally.

In other words, setting aside individual exceptions, when you find yourself asking, “What’s wrong with this group?” or “Why don’t they get it?” the odds are there’s nothing wrong with them. In fact, it’s because they do get it that they’re not ‘on board.’

It’s simply because, in the context of their current incentives, accountabilities, and the impact to their power, the program simply isn’t worth getting ‘on board.’

The Solution

How do you get sales (or any stakeholder group) on board?

It’s simple: make it worth their while to be on board. At the very least, ensure it does not conflict with their current incentives and accountabilities.

Start by identifying the purpose of the new planning process or system. What problem is it intended to solve?

For example, let’s say the purpose of the rolling forecasting process is to enable better decision-making, close gaps to objectives, or exploit new opportunities to drive profitable growth.

And to accomplish that, there must be:

- A regular monthly update on how the business is performing.

- An extension of the planning time horizon to 12 months.

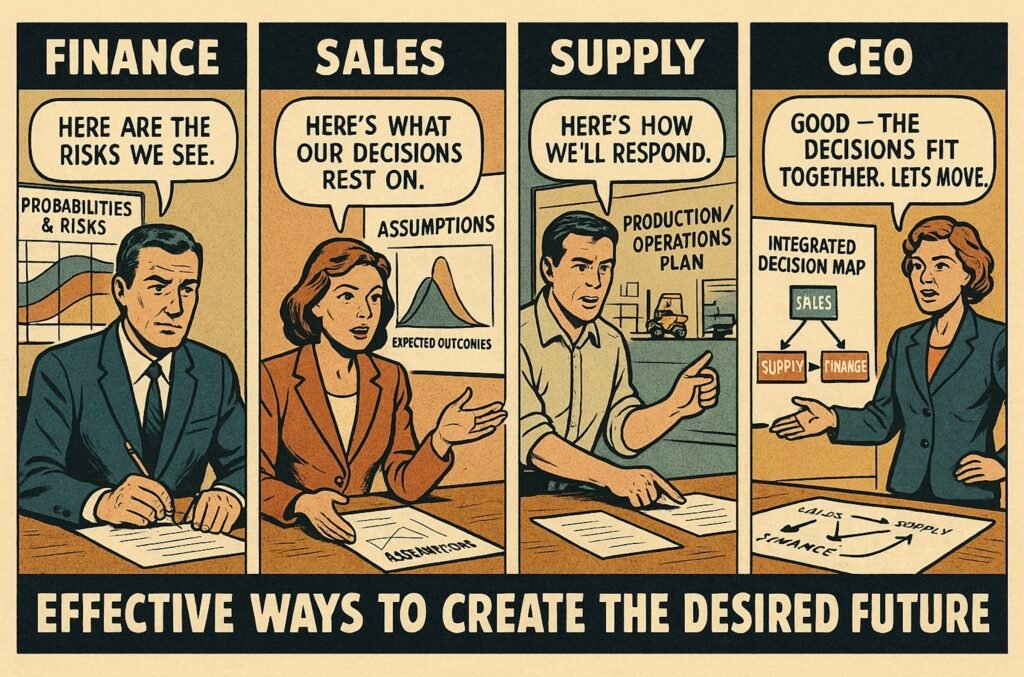

To create a behavioral change that supports this, companies must:

- Assign planning accountability to stakeholders with ‘natural accountabilities.’

- Align incentives with the desired behaviors.

- Manage changes in power dynamics.

When it comes to forecasting (e.g., predicting future sales) or planning sales (e.g., defining key assumptions and decisions), accountability for what goes into the forecast or plan—as well as the outcome (e.g., $1 billion in sales)—must lie with sales.

To do this effectively, the people creating the forecasts or plans should ideally be located within the sales organization, aligning with their natural accountabilities.

Moreover, if the desired behavior is to maintain a realistic view of how the business is performing on a monthly basis, this behavior needs to be incentivized—or at the very least, not discouraged. There are several ways to achieve this, but exploring them all is beyond the scope of this article.

One common, simple and effective approach is to establish a KPI for bias and tie it to bonuses. While forecasts can never precisely predict the future, planning can eliminate bias (systematic error), which reflects deliberate or unconscious misrepresentation of reality and distorts decisions.

The most common counterargument is that this focus detracts from ‘real results,’ such as selling more. While it may occasionally lead to unintended behaviors in individual cases, over time and on a larger scale, focusing on eliminating bias is likely to reduce far more unwanted behaviors than it creates.

What is often forgotten in these counterarguments is that bias always indicates a poor understanding—or a deliberately misleading view—of reality. This comes with a high price: additional costs, inefficiencies, and missed opportunities. By definition, these impacts affect the system as a whole and compound over time.

If the desired behavior is to have visibility (and react to changes) on a rolling 12-month horizon, ask: Why is what happens in the rolling 12-month horizon more meaningful to sales (or whichever stakeholder) than where their focus is now (for example, the calendar year, which determines 100% of their bonuses)?

If the purpose is also to increase focus of the long-term (instead of shrinking calendar year), most heavily incentivized targets must reflect that. For many it means letting go from annual target setting for the calendar year and setting dynamic targets that remain relevant over rolling 12-month horizon.

Finally, as implementing a rolling forecast process where inputs and outputs matter will likely change the current power dynamics, the company must make sure the behaviors that drive sales old behaviors are also managed

Again, there are many ways to do this (and there are many possible changes to power), and it’s out of the scope of this article to cover them all.

One example to address for instance the previously mentioned change in the ‘artistic freedom’ to tell the story about the future is to agree to build financial buffers only to financial estimate and increase safety stocks in operations.

The technical effect is the same, but the buffers that counter uncertainty are visible rather than hidden, closer to where they serve the right need, and based on the same underlying assumptions about what will be sold.

But the nature of the problem itself is not technical (where to build the buffers); it is psychological (the behaviors of different stakeholders). Therefore, to accomplish the ‘technical change,’ it is necessary to shift executives’ mindsets from deterministic to probabilistic, and shift focus from individual siloed outcomes in the short term to improving the odds to win in the long term.

The psychological side is more difficult, as it requires accepting that having a realistic but challenging target in an uncertain world means that, by definition, actual results will sometimes be higher and sometimes lower.

In such conditions, there is no such thing as being precisely on target all the time (every month, every quarter, every year). Or, to be precise, it is impossible to be precisely on target all the time while maximizing performance over the long term.

While in terms of maximizing the growth of the entire company in the long term that is no issue whatsoever, in terms of the mindsets of some individuals, it may be hard to accept, and there are no easy solutions to address that.

Sometimes, it’s not possible to change that, no matter what, other than by changing the people.

However, as long as the expectation is for performance to follow a deterministic straight line from now to the horizon of the rolling forecasting process, don’t be surprised if some people are reluctant to ‘get on board’ with that or to tell the truth about what’s happening in the business.

They are behaving exactly how one would expect them to behave.

Practical insights

- Sales are not ‘on board’ because it’s not worth being on board.

- Assign accountability for plan content and resulting outcomes.

- Align incentives with desired behaviors.

- Manage changes in power dynamics.

- In an uncertain world, there is no being exactly on target all the time.