Introduction

According to W. Edwards Deming, 94% of problems in business are system-driven (responsibility of management). While the quote is from the 1980s, and based on his subjective experience, it remains relevant to business planning today.

Most companies use the Annual Budgeting Process (ABP). It produces bonus targets, which create one of the most powerful incentives in business and, therefore, as Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger would say, determine 99% of people’s behavior.

Unfortunately, as Michael C. Jensen and Jack Welch have written, the resulting behaviors are often to lie, cheat, lowball targets, and inflate results. ABP penalizes honesty, turning business decisions into gaming exercises that hinder growth.

The simple reason is that the characteristics of the ABP—such as its purpose, cadence, and time horizon—disconnect it from real business decisions.

The purpose is often to ‘create a static plan,’ which by definition is valid only under specific assumptions. When those assumptions inevitably change, due to the unpredictability of the real world, the plans quickly become obsolete.

This happens when the planning cadence is too infrequent compared to how often the company makes real business decisions, which results in decisions being made outside the planning process.

Moreover, the time horizon is too short compared to the impacts of business decisions, which means only part of the impact is even attempted to be understood, creating an incentive to suboptimize the short term.

This leads to an absurd Sophie’s Choice for executives: whether to make decisions that result in hitting the numbers from the original, now obsolete plans, or to make decisions that maximize business performance.

The same issues apply to the second-most common planning process used in most companies: Strategic Planning (SP).

Although the impact on behaviors is less, as the plans are typically not tied to incentives, over 70 years of research shows that if SP were a medicine, in three out of four cases, it would either have no effect or make the condition worse.

The good news is that these issues, and therefore the resulting bad behaviors, are entirely due to how the company is managed, not VUCA or the inherent uselessness of planning, and can therefore be fixed.

The Problem

According to a survey, organizations that run annual planning processes make only 2.5 major strategic decisions a year, and often make these decisions despite their planning processes rather than because of them.

The disconnect between planning and decision-making creates the perception that planning is a waste of time, as plans quickly become obsolete.

As Mankins and Steele put it, “the processes most companies use to develop plans, allocate resources, and track performance make it difficult for top management to discern whether the strategy-to-performance gap stems from poor planning, poor execution, both, or neither.”

Executives question why their plans become obsolete, not realizing that their calendar-driven, opposite-to-agile, short-term cost-biased, and antithetical-to-learning planning processes are not just the root causes but are also set up that way by the executives themselves.

Calendar Driven

Annual planning cycles and rigid multi-year plans align poorly with the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the real world. Most common planning processes, like SP and ABP, are typically calendar-driven, while most decisions are made continuously—in meetings, over dinner, or on the golf course.

Calendar-driven planning processes are scheduled at specific times, such as SP from March to July and ABP from August to November. While effective for producing static plans, they are ineffective method when the goal is to make timely business decisions.

Being calendar-driven implies that the organization either delays certain decisions unnecessarily or makes them outside the planning process. Moreover, as Roger Martin points out, calendar based processes typically tend to focus on “investigating data related to issues rather than exploring and testing possible solutions.”

For instance, if strategic decisions are confined to March through July, nearly 70% of the year is lost to an artificial delay simply because “that’s when we do strategy.”

As Roger Martin has said, “People have nutty corporate tendencies to do strategy in ‘September,’ and if I were truly bloody-minded and wanted to stomp all over a competitor, I would attack them the day after the board has approved the strategy.”

When decisions are continuously made outside the planning process, the original plans become obsolete, raising the question: why invest months in SP or ABP at specific times of the year?

A common rationale is the benefit of a ‘deep dive’ into the business. While this may at first sound reasonable, a closer look shows it’s fundamentally flawed, as it implies a lack of understanding of how the business is performing when real decisions are made.

If such a deep dive is indeed needed, it means the executives are either making decisions based on a poor understanding of the business or adding artificial delays to their decisions. In either case, they’re hindering performance.

Finally, calendar-driven processes often assume that strategic, tactical, and operational decisions are independent or can be made sequentially.

In reality, optimizing decisions in isolation leads to suboptimal outcomes, as each decision influences—and is influenced by—others. Without a holistic approach that considers the interplay of all decisions, performance cannot be maximized.

Opposite to Agile

According to a McKinsey survey, companies often take too long to create plans, reducing their effectiveness. Nearly half of respondents report that it takes at least four months to develop strategic plans, and one-third say the same for annual budgets.

Both SP and ABP follow an annual cadence, meaning planning cycles are separated by 12 months. This leads to ineffective resource allocation: fewer than a third of executives believe funds are allocated effectively, and only one-fifth think their people are properly deployed across units.

An annual, calendar-driven cadence suits decisions that can be made once a year. Try listing real business decisions that fit this model—you might find it hard.

This is because agility is determined by the decision lifecycle—the total time required to make, execute, and commit to a decision.

Planning cadence adds to decision lifecycle, on average half the cadence, and at worst its full length, or in other words, decreases company’s agility correspondingly.

Consider a decision to launch new products, for example. It may take 1 to 2 months to make the decision, after which it takes 6 to 12 months to develop the product, after which it remains in the portfolio generating revenue for 3 to 4 years. In other words, it has a decision lifecycle of 4 to 5 years.

An annual cadence (assuming the process is used to make real decisions) will increase decision-making time at worst by 6 to 12 times, execution time by 100% to 200%, and overall decision lifecycle by 20% to 25%, meaning it takes that much longer to renew the entire product portfolio.

Unless such decrease of agility is acceptable, real decisions will be made outside the planning process, and the plans and numbers created in them become disconnected from reality.

Since an annual cadence adds an average of 6 months—and at worst 12 months—of lead time to decisions, it is not suited for decisions where such delays are significant.

This creates a dilemma for executives: either sacrifice the company’s agility and performance, or make decisions outside the planning process, disconnecting plans from real decisions.

This is the practical issue many executives face. While they often talk about being agile, they rarely reflect that in their planning processes—80% of companies reporting significant changes in their business within a month still use a quarterly planning cadence.

Short-term Cost Biased

Artificial planning horizons, such as the calendar year, encourage gaming and sub-optimization because many decision impacts fall outside the planning scope.

As Jack Welch has written, Anyone can manage for the short-term, and anyone can manage for the long-term, but the mark of a leader is to have the rigor and courage to do both simultaneously.

Consider the decision to develop new products. If it takes 6 to 12 months to develop the products, followed by 3 to 4 years of revenue generation, by making the decision, executives impact the company’s performance 4 to 5 years in the future, regardless of uncertainty.

However, an artificial planning horizon of 12 months captures only 20% to 25% of that impact at best, and at worst only about 1% to 2%, assuming product launch decisions are made throughout the year.

Furthermore, since costs occur upfront while revenues are realized later, a 12-month planning horizon biases decisions toward costs. This means that the characteristics of the planning process—not VUCA or the inherent uselessness of planning—result in plans where long-term growth is overlooked and costs are exaggerated.

Some argue that ‘it’s impossible to plan far into the future,’ but what they really mean is that it’s impossible to create static plans that far ahead. While the latter is true, executives still make decisions with long-term impacts, such as developing new products, outside their planning processes.

This disconnect between planning and decision-making results in decisions made in isolation, ignoring the context and interdependencies of other decisions.

This neglects the fact that it is impossible to maximize a system’s value by optimizing individual parts in isolation, which means that making long-term decisions outside a holistic planning process likely hinders overall performance.

On average, an ABP with a 12-month horizon is suitable for decisions with impacts no more than 6 months into the future, yet even then it only captures the full impact about half the time.

Most decisions that fit this criterion are operational with minor impacts, such as which SKU’s to produce, while major business decisions, like resource allocations (e.g., new product launches), typically have impacts lasting several years.

Antithetical to Learning

According to Mankins and Steele, “less than 15% of companies regularly compare actual results with strategic plans.”

‘Plan creation’ processes like SP and ABP are antithetical to learning because they lack key components of strategic learning: gathering feedback, testing hypotheses, and making necessary adjustments.

Executives obsess over ‘hitting the plan’ but fail to question whether they should. They focus on ‘how did we perform?’ but overlook the more important question: ‘should we alter the course?’

In other words, SP and ABP exemplify single-loop learning, where underlying assumptions go unchallenged. It’s like following a GPS onto a closed bridge without questioning if the route is still viable.

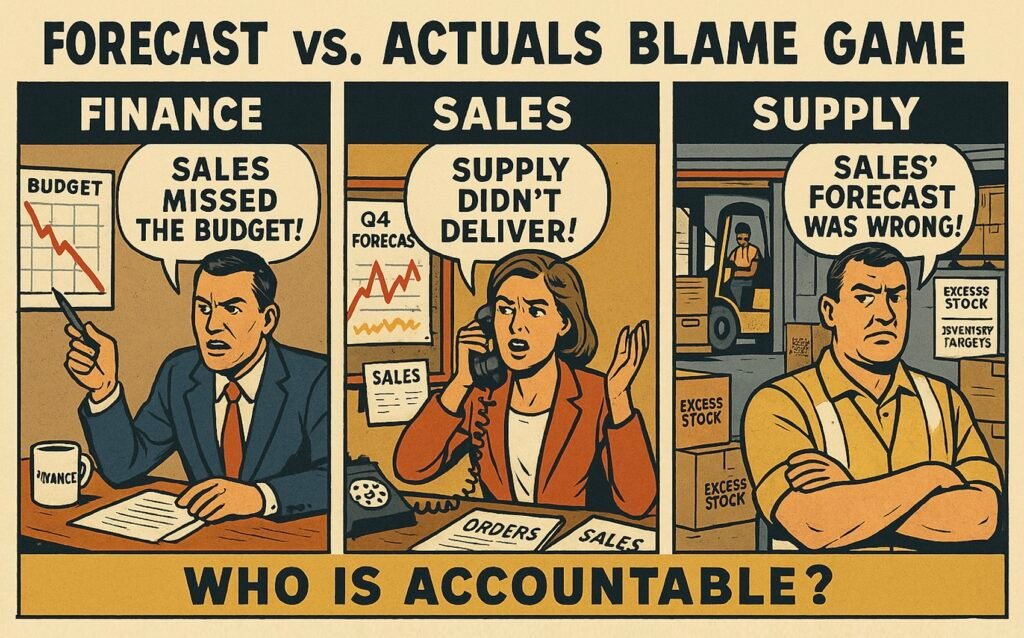

The inability to learn prevents the organization from understanding whether nonperformance is due to poor decisions, poor execution, both, or neither. This results in holding on to bad decisions when they should be revised, revising decisions when execution should be improved, and misplacing blame when neither is at fault.

This failure to learn results in ABP to “we’ll make the gaps up in Q4”, without real-world context, and to ‘Venetian Blinds’ or ‘Hairy Backs,’ in SP, where failing strategies continue to be funded rather than replaced with better alternatives.

Furthermore, most companies maintain separate performance management processes that compare actuals to the Previous Year (PY) or the Annual Budget (AB).

At best, these reviews amount to little more than ‘reporting the weather’—executives review results and adjust plans to match variances, rather than addressing the underlying issues.

At worst they lead to decision that hinder performance as executives fail to recognize that neither of what is been compared is valid: AB or PY doesn’t represent expected performance, and the actual value doesn’t represent actual performance

This is because the assumptions and decisions have already changed from AB and PY, and the expected performance is determined by the latest decisions and assumptions, not what was assumed or decided several months ago.

As learning in probabilistic systems, like the real-world, is not trivial (as explained here), it is also impossible to say based on single actual outcome, how much of that is significant and how much meaningless noise.

Therefore, ironically, what most companies call ‘performance management,’ is in fact about gaps between what the expected performance shouldn’t have been and what the actual performance wasn’t.

And even if the gaps are sensical, the learnings aren’t used to revise the plans made in ABP or SP. The reason for this is often stated that the ABP produces a target, while the month-end process produces a forecast, and the job is to close the gap between the two.

However, this fails to recognize that the targets are often so flawed, that they are not worth hitting, which is explained more in detail here.

Further, even if the target would be valid, understanding the difference between actual and target help little to improve performance, unless the last plan the company followed had no gap to the target.

If it did, as is often the case, the key question for performance improvement is how the company executed the last approved plan. For example, let’s say last year sales were $100 million, the budget $110 million, and the actual were $90 million.

The budget was based on assumption that market grows 5%, and under that assumption the company decided to hire more people. While in reality the market declined 10%, and the company had already decided to lay off people months ago, and based on these new assumptions and decisions projected sales were $90 million.

Gap analysis between $110 million and $90 million, or $100 million and $90 million, tell nothing about how the company performed, nor what new it can learn to see better future gaps and opportunities.

The Solution

According to McKinsey research, having the right process is six times more important than analysis in improving revenue growth and profitability.

Executives must recognize that decision-making is not a one-time event but a process that unfolds over time. As BCG partners put it, “planning cannot be a one-time thing. It needs to be an all-the-time thing,” which, as Ed Barrows characterizes, is “a more realistic approach than the once-a-year planning meeting that still dominates many corporate planning efforts.”

To accomplish this and stay connected with real business decisions, executives need to make planning a continuous process. Its cadence should be 20 times faster than typical decision lifecycles, the time horizon should account for decision impacts, and there must be a feedback loop to continuously revise plans as assumptions change and new decisions are made.

Make Planning a Continuous Process

According to McKinsey, many better-run companies use rolling budgets to keep their plans current.

As Michael Mankins wrote: “To better cope with extreme volatility in crafting strategy, companies must change the way they approach strategic planning. They must evolve from a static, plan-then-do model to a dynamic and continuous approach to decision-making and execution.”

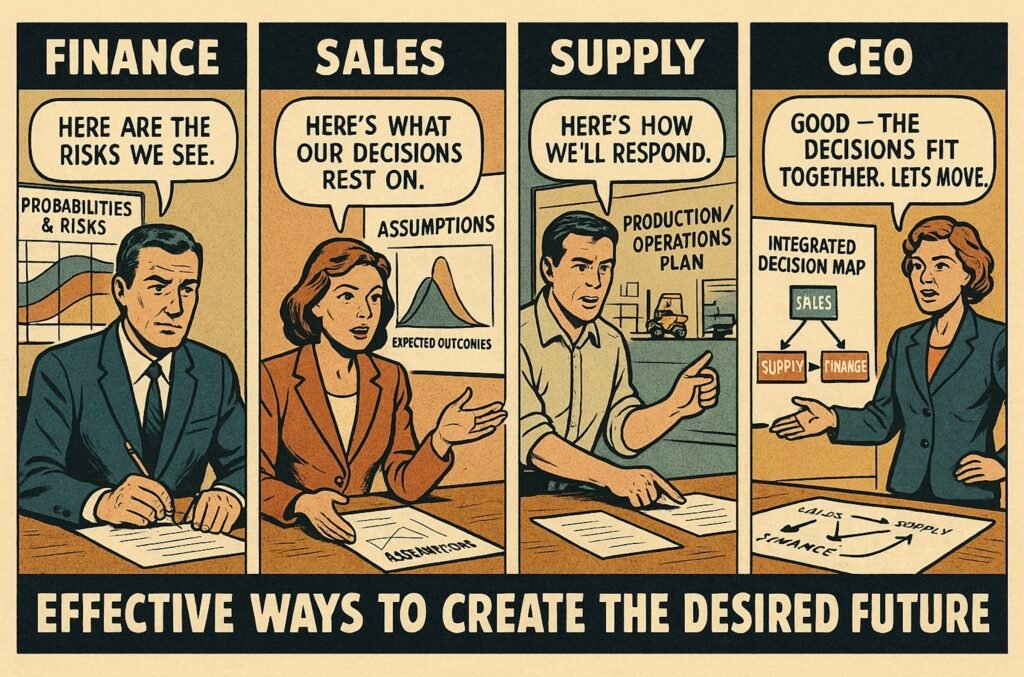

Since decision-making under uncertainty requires debate of assumptions and probabilities among cross-functional stakeholders, companies need a process that establishes a common language between them.

Research shows that executives who make good decisions recognize the importance of approaching decision-making as a continuous process. In contrast, those who make poor decisions tend to view decisions as isolated events under their control.

To align planning processes with real business decisions, planning needs to be continuous, rather than calendar-driven, because organizations make decisions continuously, not only at specific times of the year.

‘Continuous’ doesn’t mean real-time or constant; it means a regular cadence. Just as being in the gym all the time would be overkill, and going only from April to July wouldn’t be sufficient, finding the right cadence, like four times a week, is the key.

Similarly, instead of running an annual budgeting process from August to November, companies should implement a tactical decision-making process that allocates resources, for example, on a monthly cadence.

A monthly cadence means that each planning cycle takes one month, with specific activities, such as review meetings, occurring regularly. As a result, plans are updated after each cycle, ensuring the company always executes the latest plan, not an outdated one from three, six, or some other arbitrary number of months ago.

Align Planning Cadence with Decision Lifecycle

According to BCG, top quartile companies complete budgeting process in four weeks, and according to Mckinsey companies with shorter planning cadencies outperform their peers on revenue growth and return on capital.

Establishing the right cadence allows for easier plan adjustments, whereas creating static plans can lead to an overemphasis on accuracy because they cannot be revised later, and small mistakes may compound and derail the plans.

According to a study by McKinsey, “firms that actively reallocated capital expenditures across business units achieved an average shareholder return 30% higher than the average return of companies that were slow to shift funds” (as cited in Why Strategy Execution Unravels—and What to Do About It).

When the focus is on making business decisions instead of creating static plans, planning cadence must be significantly shorter than the decision lifecycle, ideally by a factor of at least 20.

For example, tactical decisions like launching new products, were decision lifecycles are several years, require at least a bi-monthly cadence. Operational decisions with lifecycles of just a few months, such as which SKUs to stock, need a minimum weekly cadence. Conversely, the annual cadence that most use is better suited to decisions with lifecycles of 20 years or more.

This is because when the planning cadence is less than 20 times the typical decision lifecycle, the added decrease in agility is negligible: on average only 2.5%, and at worst only 5%.

The numbers are illustrative, not to be taken literally, as what constitutes a negligible decrease in agility is context-specific, and also because companies make and should be able to make decisions with different lifecycles using the same planning processes.

What is important is that for most decisions, most of the time, the decrease in agility is deemed negligible. Otherwise, real decisions will be made outside of planning processes. However, it is also important to note that while most only consider the impact of the time to make and execute a decision on agility, at a system level, it’s in fact the entire decision lifecycle that matters.

This is because of two reasons. First, all decisions are valid only under certain assumptions about how long it takes to execute and commit to them. Second, all decisions need to account for uncertainty during that period.

Consider the example of launching new products. Even if a company could reduce the time to make and execute the decision to less than a day, and by some miracle do that cost-effectively—both extremely generous assumptions—that still wouldn’t increase the company’s agility in adjusting its product portfolio to market needs in a day, unless those products could also generate the same revenue in a day that they used to generate in three to four years.

If the decision lifecycle were still 3 to 4 years, it would take that long to renew the product portfolio, even if decisions could be made and executed in real time. In such a case, a planning cadence of 2 to 3 months would reduce agility by roughly 5%, while a ‘real-time’ cadence would reduce it by 0%, even though decision-making and execution times may have been reduced by ‘thousands of percentages.’

In other words, contrary to what software providers often claim, it is a misconception that having real-time information automatically leads to better business decisions or significantly improved agility.

Since organizations make significantly different types of decisions, aligning the cadence and time-horizon means that an organization should have multiple planning processes.

For example, one for strategic decisions with a quarterly cadence, one for tactical resource allocation decisions with a monthly cadence and one for operational decisions with a weekly cadence.

Align Time-Horizon with Decision Impacts

To account for decision impacts, the planning system’s time horizon must align with them. This ensures that all relevant factors can be considered, improving the likelihood of better decision outcomes.

The fact that it’s impossible to know what will happen over that time-horizon with any certainty is irrelevant. This is because, by making decisions, executives are shaping the company’s future over the horizon of those decision impacts.

For example, if the decision to launch new products affects the company’s future 4 to 5 years out, the planning process time-horizon should reflect that. The decisions may be based, for instance, on the assumption that the sustainable product segment will grow 20 to 30% annually.

Whether it does or doesn’t, it doesn’t change the fact that for the next 4 to 5 years, a significant part of the company’s product portfolio will consist of sustainable products, impacting its costs and its ability to generate revenue.

Even if the company cannot predict with precision or a high degree of certainty how much revenue it will generate, it can always improve its odds by enhancing its understanding of possible future scenarios.

Moreover, even if it were impossible to make any predictions, the company can still improve its ‘odds to win’ by aligning stakeholder actions. For example, changing the product portfolio may have interdependencies with suitable customer segments and production capabilities.

When product management shifts 20% of the portfolio to sustainable products, the company’s ‘odds to win’ will be higher if sales actions and operations investments are aligned with the impacts of these decisions, rather than if they aren’t.

Since organizations should have several different planning processes with different cadences, those processes should have different time-horizons.

For example, one for strategic decisions a rolling 5 to 10-year time-horizon, tactical resource allocation decisions a rolling 3 to 4-year time-horizon, and operational decisions a rolling 20 to 30-week time-horizon.

Correspondingly, the level of detail in each plan should be determined by what is relevant for the decisions, not by what can be predicted or what would need to be predicted to feel comfortable.

For instance, when shifting the strategic where-to-play decision to sustainable products, the appropriate level of detail may be the overall annual market size and the share of sustainable products in the company’s portfolio, while operational decisions, like which SKUs to stock, would require item- and week-level information.

Create a Feedback Loop to Revise Plans

“However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.”

Stanford professor Robert Burgelman wrote, “Successful firms are characterized by maintaining bottom-up internal experimentation and selection processes while simultaneously maintaining top-driven strategic intent.”

According to McKinsey, implementing a system to measure and monitor progress can greatly enhance the impact of the planning process, and Mankins and Steele propose embedding learning within a rigorous framework to determine whether a shortfall is due to poor execution or an unrealistic plan.

Therefore, the planning processes used to create and revise plans must also serve as performance management systems that track actuals against the plans.

To shift focus from creating static plans to making business decisions, the planning process must use double loop learning. This means instead of asking ‘How to hit the plan?,’ the question should be ‘What should the plan be?’

The planning processes must include a feedback loop to test the validity of assumptions and the quality of decisions in the plans, allowing for continuous revision.

In other words, as put by McKinsey director Lowell Bryan: “companies can’t control the weather, but they can design and build a ship, and equip it with a leadership team, that can navigate the ocean under all weather conditions.”

To improve performance, the key is to understand what, in the last view of the world (the assumptions), has changed to be able to see future performance gaps earlier and make the necessary new decisions to close those gaps.

To do this effectively, planning systems must identify: 1) which gaps are meaningful; 2) which 20% of assumption changes account for 80% of the gap; and 3) how those assumption changes impact the future.

For example, if expected sales were $100 million, actual sales of $80 million may be significant, while actual sales of $95 million might not be, or vice versa.

There may be dozens of reasons impacting the gap: “the market didn’t grow,” “consumers found prices too high,” “availability was poor,” “competitors launched discount campaigns,” “retailers had high stocks,” etc.

Instead of listing those reasons in a separate process, the planning process should identify that $12 million of the gap can be explained by 10% segment growth, instead of the assumed 25%, and another $5 million by price increases deemed too high.

The results of this analysis must be inputs for the next planning cycle to debate the assumptions in the plans. If the original assumption was 25% segment growth, but actual growth was 10%, what should be assumed about the future?

This enables companies to identify an even larger $30 million gap in the future, as the segment is now expected to slow to just 5%. This may indicate a need to review and revise the strategic where-to-play decision.

In another scenario, if the assumption of 25% segment growth remains valid, the company might identify that it was the execution of the where-to-play decision that should be improved. For example, if sales forecasted only 10% growth, operations may have been prepared for just that.

The practical implication, however, is that instead of drawing conclusions from single outcomes—like the $20 million gap—companies’ planning systems must consider several outcomes over time to discount the impacts of luck and better understand when they should simply stay the course.

From Killing Growth to Driving It

ABP is a 100-year-old system that has remained virtually unchanged for the last 50 years. During the same period, best practices in management and leadership have shifted from rigid, top-down command-and-control to agile, inclusive empowerment.

Executives dissatisfied with their company’s performance should first consider modernizing these systems before blaming the organization for ‘poor execution’ or the behaviors those systems incentivize.

Even if we ignore the paradigm shifts in leadership best practices, ABP and SP have such major flaws that disconnect them from real business decisions, making them hard to justify.

They are typically on/off only part-time (e.g., ‘in spring’ or ‘in fall’), and their annual cadence is too infrequent for most decisions, while organizations make decisions continuously, which is why real decisions are made outside of these processes.

Their planning time horizons neglect major decision impacts, leading to short-term cost biases at the expense of long-term growth. What’s worse, they lack mechanisms to test and revise plans as core assumptions and decisions change.

As a result, the likelihood that the plans they create will become obsolete is practically certain, as avoiding this would require the company to make no decisions and for the real world to stand still—both clearly absurd conditions.

Since bonuses are often tied to numbers from the original, now obsolete plans, managers face a Sophie’s Choice: either ‘hit the numbers’ to secure their bonuses or make decisions that drive long-term growth.

Managers can’t be blamed for choosing the former when the systems they’re forced to operate in compel them to act that way.

It is the executives’ responsibility to change the systems so that it’s in the managers’ best interest to act in a way that is also in the company’s best interest in the long run.

To be able to accomplish that in practice, it may also be necessary to change target setting, as poorly set targets not only fail to require such planning systems but also drive behaviors that render these systems ineffective and unnecessary.

Practical insights

- Planning processes that misalign with real business decisions kill growth.

- Replace calendar-driven planning processes with continuous processes.

- Set the planning cadence shorter than the decision lifecycle by a factor of 20.

- Extend planning horizon to cover decision impacts, regardless of uncertainty.

- Create a feedback loop from real data to continuously revise plans.